9 iconic black history landmarks to visit near Georgia

This story originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of Living Intown magazine.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., opened Sept. 24, 2016, and obtaining passes still seems about as difficult as scoring "Hamilton" tickets.

The long and winding history of the Smithsonian black history museum

Featuring a collection with more than 36,000 historical elements, the new Smithsonian Institute museum has quickly become one of the country’s most popular sites for exploring black history.

RELATED: 6 must-see Atlanta landmarks

If you can’t make it to the nation’s capital but still want to expand your knowledge of African-American culture and heritage beyond Atlanta’s avenues, consider the following southeastern cities. All within comfortable driving distance, they offer windows into black life in the past with poignant reflections on slavery, the civil rights movement and culture.

Charleston, South Carolina

Possibly the most noteworthy tourist site in Charleston is the Old Slave Mart Museum.

When Charleston passed an ordinance in 1856 requiring the sale of slaves be moved off the street, Thomas Ryan opened Ryan’s Mart. Before the ordinance, according to the museum’s historical interpreter Christine Mitchell, Ryan was already a slave trader conducting sales in the enclosed area between a former German fire station and a private residence. Buildings included a four-story jail for slaves, a two-story kitchen, and a morgue called the “dead house” used for isolating the sick.

Mitchell moved from Atlanta to Charleston in 2013 to be near family, and is a third-generation descendant of slaves who lived in the community. “To be here and to help educate people who are coming here from all over the world, I am giving honor to the ones that never had a voice,” she says.

Museum visitors get a sense of the experience of bondage through placards and audio recordings.

"We have some insight into what slaves thought," administrative manager Richard Ogden says. "It was very dehumanizing. As men would get older, [traders] would pull out their white whiskers and color their hair to make them look younger."

The museum is a draw for students, teachers and other scholars, but the organization recommends that visiting children be at least in the fourth grade.

Other highlights in Charleston include McLeod Plantation Historic Site, established in 1851, which presents a detailed, frank journey into life during slavery and the transition to freedom.

Middleton Place, a former rice plantation, has several self-guided walking tours, including a 60-minute exploration of where African-Americans lived as slaves and later as free people. The tour includes a chapel, cemetery and housing units.

The Aiken-Rhett House Museum, based in the antebellum home of former South Carolina Gov. William Aiken, provides a look at how one of Charleston's upper-class families lived. A tour starts in the warming kitchen, where slaves worked, and continues into the work yard and slave quarters behind the main house.

Savannah, Georgia

Like Charleston, Savannah puts a spotlight on African-American history against a backdrop of picturesque architecture. The Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum is named for a former pastor of the historic First African Baptist Church. Considered the father of Savannah's Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Gilbert started 30 Georgia chapters of the NAACP. The museum's three floors feature historic photographs and exhibits.

“We’ve got a great story here and Atlanta connections,” says director Vaughnette Goode-Walker. “Hosea Williams was a member of the Chatham County Crusade for Voters and was arrested [in 1963].”

The 11,800-square-foot building on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard was constructed in 1914 with an African-American contractor, Robert Farrow.

On Montgomery Street, First African Baptist Church was a safe haven for runaway slaves traveling through the Underground Railroad. A diamond-shaped design in the floor is peppered with small holes, below which slaves could hide or pass through a 4-foot-high space. Slave masters ignored the holes because the openings typically allowed wood to breathe, says church pastor Marco George.

The Owens Thomas House is one of many homes or former plantations that provide a glimpse into the past. Located in downtown Savannah, it was built in 1816 by prominent English architect William Jay. Visitors can take guided tours of the main house and slave quarters.

Sightseeing excursions, such as the Freedom Trail Tour hosted by Johnnie Brown, take visitors to plantations and historic landmarks. Brown and other guides point out graves, whipping trees and the sites of other historic events to form a narrative of the past.

Charlotte, North Carolina

Mary Harper, a graduate student in the 1960s at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, approached then professor Bertha Maxwell with an idea for a cultural center to preserve and celebrate African-American heritage and contributions. In 1974, they opened the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American-Arts and Culture.

The center features permanent and visiting art exhibits, performances, author talks and other events. Gantt’s consulting curator is Michael Harris, associate professor of art history in Emory University’s Department of African American Studies.

That’s not the Center’s only Atlanta connection.

“It’s interesting because we do have a number of people who come from Atlanta for weekends and say they learn of us by Googling,” says Bonita Buford, chief operating officer.

In February, an abstract art exhibition titled “The Future is Abstract,” curated by Dexter Wimberly, will highlight the work of four artists through painting and mixed media.

Birmingham, Alabama

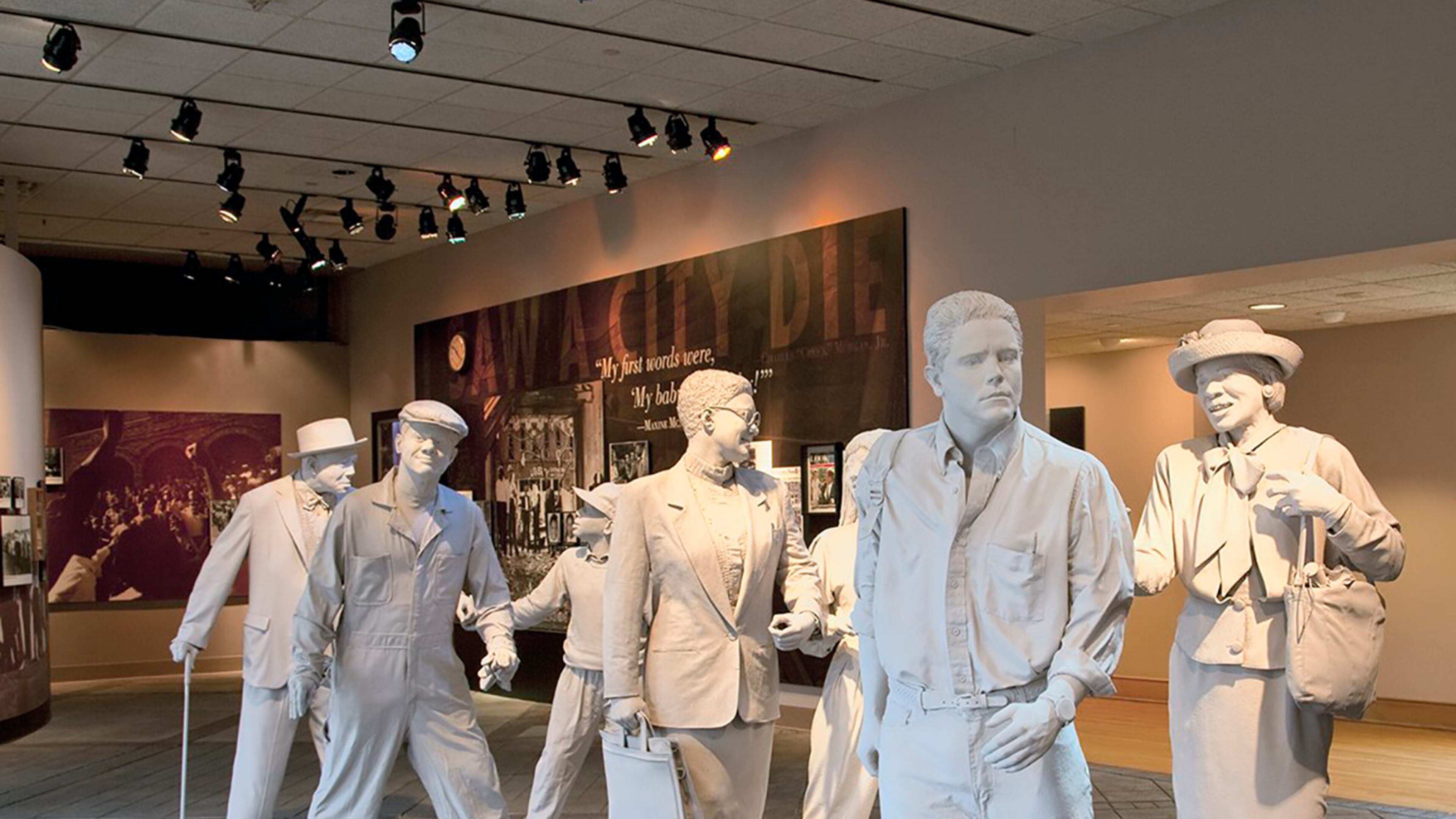

Exhibits inside the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute illustrate the city's civil rights struggles and segregation history with elaborate replicas, including segregated classrooms and "white" and "colored" water fountains. Photographs depict events such as the firebombing of the Freedom Rider bus in Anniston. A tall, vibrant 1930s photo captures the Fourth Avenue black business district. A courtroom scene depicts the stark isolation that African-Americans experienced on trial.

"We have the jail cell door that Dr. [Martin Luther] King was [behind] when he was here in 1963," says Ahmad Ward, education and exhibition director of the BCRI, which opened in 1992. "We received a bench from the cell about 13 years ago."

King’s confinement during that Easter weekend inspired his landmark “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which he wrote, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

RECOMMENDED VIDEO: Freedom Riders 50 years later: The reason