Fulton County doesn’t need a new jail. Here’s why it’s a bad investment.

Editor’s note: The Fulton County Jail is in subpar shape and operates under a consent decree agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice. Sheriff Patrick Labat has called for building a new jail, but Fulton officials have proposed to the Board of County Commissioners a property tax increase to pay for jail improvements instead. This essay is a view on the jail debate. Agree, disagree or have another take? Email letters of 250 words max to letters@ajc.com or inquire to opinion editor David Plazas at david.plazas@ajc.com on writing a longer guest opinion column.

The debate surrounding the construction of new jails in America is often shrouded in controversy, with some critics arguing they are too costly, perpetuate a cycle of crime and disproportionately impact Black and brown communities.

Proponents champion the building of jails as a solution to the inhumane overcrowding of inmates and a way to provide specialized services for the mentally ill.

When I was first elected as Fulton County Board of Commissioners chairman in 2006, I was confronted with three crises:

- the imminent closure of Grady Hospital

- the public perception of a dysfunctional and racially divided board of commissioners

- a previous federal consent decree levied by U.S. District Court Judge Marvin Shoob because of understaffing and the extreme overcrowded conditions at the Fulton County jail.

At that time, the jail housed nearly 3,500 inmates. The most immediate resolution was to build a new jail, but I resisted.

Instead, I advocated for diversion strategies that effectively addressed overcrowding without compromising public safety and better resource usage, particularly investing in young at-risk individuals, jail reentry programs, and mental health and drug accountability courts.

Jails create disproportionate impacts for marginalized communities

This approach offers a lens into broader systemic failures within the United States criminal justice system.

Jails primarily function as pretrial facilities, holding individuals who are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

This unique context highlights the disproportionate impact of overcrowding on vulnerable populations, such as young Black and brown men who are impoverished and lack formal education.

This population lacks access to the resources necessary to avoid entanglement with the criminal justice system in the first place.

Financially, the implications of building new jails are profound. County budgets fund a wide range of services, including libraries, community health centers and elections.

During my tenure, the operation of the criminal justice system, including the jail, the district attorney’s office, and the Superior, State and Magistrate courts constituted 40% of the annual general fund budget.

Building a new facility will represent one of the most significant expenditures in a county’s annual budget.

I consider the allocation by county commissioners of $1.2 billion for a new jail facility plan in Fulton County as financially irresponsible.

Instead of constructing additional incarceration facilities, the board of commissioners should focus on proactive investments that address the root causes of crime, particularly among our youth — who are often the most affected by systemic inequalities.

Georgia’s incarceration rate is far too high

The United States has the highest rates of incarceration of any other country in the world, with nearly 2 million people in federal and state prisons, as well as local jails, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. The state of Georgia ranks in the top 5 among states with an estimated population in its prisons of nearly 47,000, according to the state Department of Corrections.

Coming closer to home, the statistics also indicate that metro Atlanta has one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation.

With a population of approximately 4 million, per the Atlanta Regional Commission, five counties in metro Atlanta — Fulton, DeKalb, Clayton, Cobb and Gwinnett — house around an average of nearly 12,000 inmates daily, according to the National Association of Counties, Fulton County government and DeKalb County Court:

- Clayton: 1,900

- Cobb: 2,100

- DeKalb: 2,200

- Fulton: 2,899

- Gwinnett: 2,900

In contrast, Rikers Island, the largest jail in New York City (which has also been under a federal consent decree since 2015) serving a population of nearly 9 million, sees an average of 6,150 inmates daily with a capacity for 9,056. This comparison raises critical questions about our reliance on punitive measures rather than preventive ones.

During my tenure, I rallied my commission colleagues to embrace the concept of criminal justice reinvestment, by urging a shift of funds from traditional incarceration toward preventive and interventive strategies. I believed that jails should not be just a building, but they should provide diversion services that would be a road map for turning one’s life around.

This approach sought to dismantle the “cradle to prison pipeline,” a cycle exacerbated by social disadvantages and a lack of support for youth. By diverting funds from new jails into programs that offer education, mental health services, youth mentorship and community development, we can create pathways out of poverty and violence. Investing in youth today could reduce crime rates and enhances public safety in the long term.

County should foster well-being and empowerment

The Board of Commissioners cannot do it alone and must include criminal justice partners. During my tenure, I initiated the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, which brought together diverse stakeholders — including law enforcement, judges and community organizations — to collaboratively address jail overcrowding without compromising public safety. This initiative not only alleviated the overcrowding issue but also reinforced the idea that successful interventions come from understanding and supporting our communities rather than merely policing them.

The role of government extends far beyond incarceration; it’s about fostering the well-being and empowerment of its citizens. I wish to emphasize that Fulton County public officials must concentrate on identifying and addressing fundamental issues instead of propagating a cycle of imprisonment through unnecessary infrastructure.

In conclusion, while constructing a new jail might seem like a pragmatic response to chronic overcrowding, a closer examination reveals that this approach is inherently flawed.

The Fulton County case exemplifies a crucial understanding that meaningful solutions demand a holistic perspective on criminal justice reform and resource allocation. Instead of building additional facilities for incarceration, communities should prioritize investing in preventive measures and programs that uplift at-risk youth.

This paradigm shift moves us from merely managing the symptoms of broader societal issues to actively addressing their root causes, ultimately fostering healthier and safer communities. By prioritizing people over punishment, we can pave the way for a more just and equitable society.

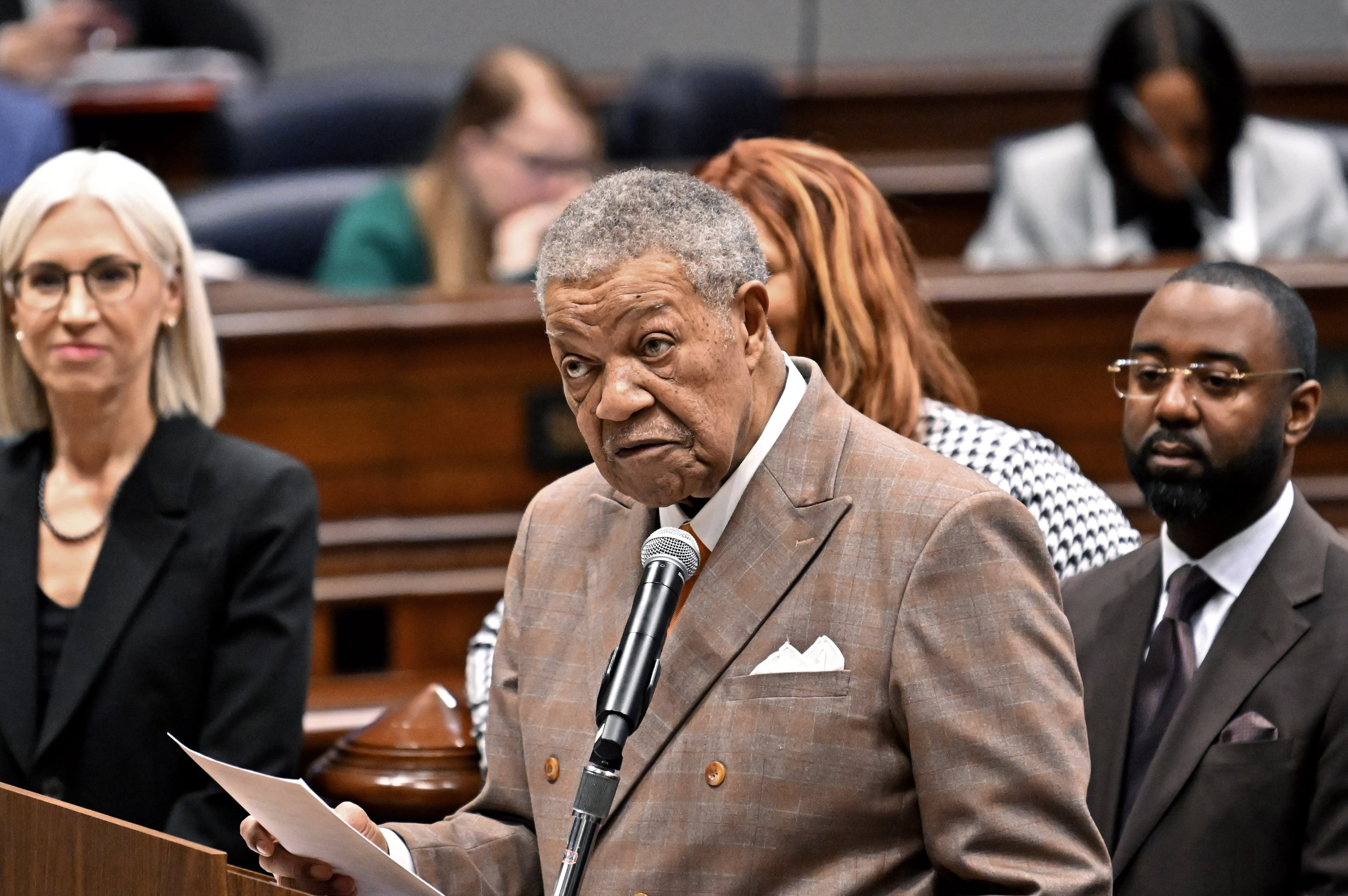

John H. Eaves, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution contributing columnist, is a former Fulton County Commission chairman and a senior instructor in the Department of Political Science at Spelman College.