A piece of Coca-Cola’s Atlanta history now could have a new chapter

The new owner of a curious Victorian structure in downtown Atlanta found something tucked away in the attic, perhaps for a century.

It was a 5-gallon Coca-Cola barrel, likely dating back to the early 1900s when it contained the syrup needed to make the now-famous soda.

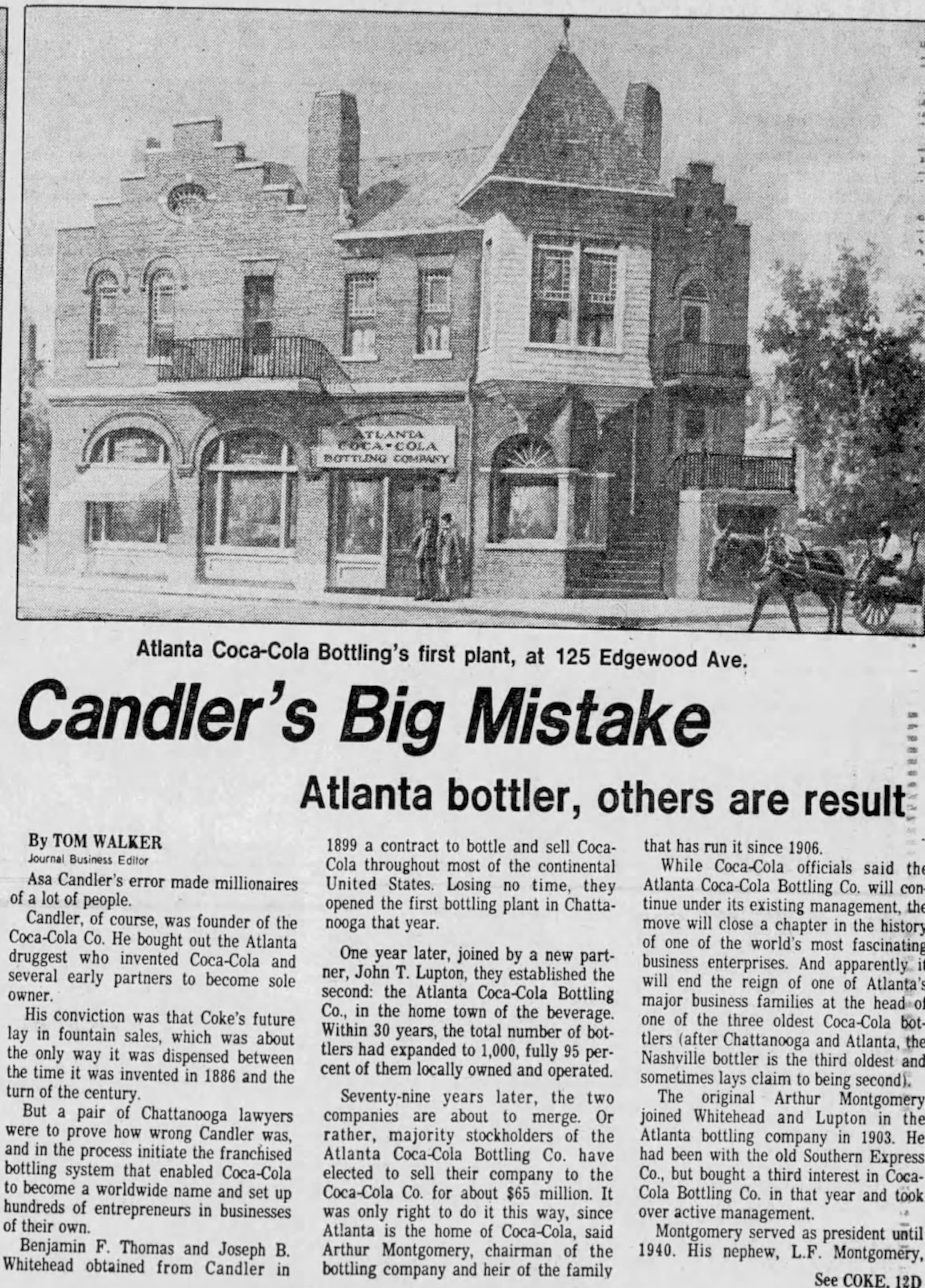

The relic harkens back to the quiet history of the red-brick building at Edgewood Avenue and Courtland Street, an intriguing sight with its curved windows, chimneys and gabled roof.

People commuting along Courtland toward the state Capitol might not know the structure is the last remaining in the city from Coca-Cola’s earliest days.

The 135-year-old building was the first Atlanta bottling operation for Coca-Cola, a reminder of when the beverage company went from just being served at the soda fountain to becoming mass-produced.

Now, an investor has purchased the building at 125 Edgewood Ave. Jeff Notrica, president of Inman Park Properties, bought the building for nearly $1 million in September, according to Fulton County property records.

Notrica said he was alarmed by the loss of other nearby historic buildings. He said he plans to revive the faded exterior of 125 Edgewood and bring in a new tenant to liven up the street corner.

“It’s extremely exciting to be involved with something that is so quintessentially Atlanta,” Notrica said during an exclusive tour of the property in January.

Notrica said he hopes to find an occupant to transform the roughly 9,000-square-foot space into something “community activating,” such as a coffee house, brewpub, comedy club or live music venue, he said.

The building served for decades as the Baptist Student Center for Georgia State University, which said it relocated in December 2024 to 145 Auburn Ave. An affiliate of the Georgia Baptist Mission Board sold the property.

Notrica’s acquisition comes as other nearby historic buildings are endangered or being torn down, such as Sparks Hall and 148 Edgewood Ave., which Atlanta preservationists have decried.

His purchase also coincides with a wave of reinvestment in downtown Atlanta, from Georgia State’s more than $100 million transformation of its downtown campus to the towers and entertainment venues rising at Centennial Yards.

“The reactivation of that space is huge,” David Mitchell, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center, said of 125 Edgewood, a project he said he is supporting. “It can provide services for (Georgia State) students. It can connect people to Atlanta’s past.”

Notrica, an Atlanta native, has an affinity for historic properties. He owns the Callan Castle in Inman Park, a mansion where former Coca-Cola owner Asa Candler once lived. It was Candler who authorized the bottling system that ultimately led Coca-Cola to become a global brand.

Notrica today serves as chairman of Savannah’s Historic Preservation Commission.

Through the years, he has owned many history-rich Atlanta properties, such as Hotel Clermont and a former firehouse at 30 North Ave. Among other projects, Notrica says he rehabbed what once was a boarded-up automotive repair building at 309 North Highland Ave., now home to pizza place Fritti.

But his renovation plans haven’t always panned out, for example, during the Great Recession. Some properties that Notrica owned, including the Hotel Clermont and the “Castle” in Midtown, ultimately went back to the lender, Fulton County property deeds show.

When asked how he would apply what he’s learned from past projects to 125 Edgewood, Notrica said, “Anything that I’ve gathered through the time and past experiences, we will certainly add to this. … One of the things is just being more in the public of what we’re trying to do here and to move this forward.”

At 125 Edgewood, Notrica has hired Alison Gordon, a fourth-generation Atlantan who said she has a love of historic properties and who runs Beehive Collaborative Project Management Services.

Gordon said she is working with the Atlanta Preservation Center on accurately restoring the exterior of the building, including the worn shingles near the grand entrance and its spiraling staircase.

“We are focused on preserving the building first and foremost,” Gordon said. “So we are focused on the exterior first in terms of timeline.”

While in discussions about renovations, the team is also actively listing the property for sale for nearly $3 million. That “just keeps the discussion open,” said Danny Glusman of Widespread Commercial Group, the broker on the listing, who is also handling leasing efforts.

“Ideally, we would love to rent it out, but sometimes a project like this is going to require an extreme capital commitment from a tenant,” Notrica said. “And sometimes, tenants are more comfortable owning the property.”

The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its exterior is designated as a landmark by the city of Atlanta. That could make it eligible for state historic tax credits, a Georgia Department of Community Affairs spokesperson said.

“It is a highly significant property and one that needs to be preserved,” said W. Wright Mitchell, president and CEO of The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation. “It needs to be adaptively reused and revitalized.”

The building at 125 Edgewood was constructed in 1891, making it one of the oldest left in the urban core, said Mitchell.

“That building has been there and been witness” to many notable events, Mitchell said, from the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906 to the Civil Rights Movement. “It has served as a visual reminder to our achievements and our successes and our hopes and dreams.”

The very first glass of Coca-Cola was poured in downtown Atlanta in 1886 at the long-demolished Jacobs’ Pharmacy.

Candler would buy the recipe two years later, and until 1899, Coca-Cola was only a soda fountain business, said Phil Mooney, the former Coca-Cola archivist and historian for 36 years.

That was until Candler struck a deal. Lacking the capital to expand at a rapid rate, in 1899, Candler sold the bottling and distribution rights for $1 to a pair of Chattanooga lawyers, Benjamin Thomas and Joseph Whitehead.

Thomas and Whitehead first opened a bottling plant in Chattanooga and then expanded operations to Atlanta, taking the space at 125 Edgewood in 1900.

“People used to laugh and say Candler made a really dumb deal,” Mooney said. “In fact, it was really brilliant, because the company never would have been able to expand as rapidly as they did unless they had other financial business partners.”

The Atlanta Coca-Cola Bottling Co. and its parent company, the Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Co., would operate at 125 Edgewood only until 1901. Coca-Cola later had bottling operations on Spring Street.

Still, the decision to bottle the soda would ultimately change Coca-Cola’s business model, Mooney said.

Coca-Cola today has bottling operations in more than 200 countries and has reduced its investments in those businesses in recent years, letting third parties own and operate many of those facilities.

Coca-Cola sets the global strategy, promotes its beverage portfolio and sells syrup and concentrate. Its bottlers produce and distribute the drinks in the local markets.

“Bottling changed the whole business, because now you had a product that was transportable,” Mooney said. “You could take it anywhere that you wanted. … It just changed the dynamics of the business.”