It’s the near future, or maybe not: Rachel, a fierce, 28-year old, “scavenger” and her partner, Wick, a biotech engineer drunk on “alcohol minnows,” struggle to survive in a destroyed, nameless city. The population has been victimized by a malevolent corporate entity known as the Company. Furthermore, all are entangled in a titanic running battle between a giant flying bear called Mord and his equally tyrannical nemesis, the Magician, whose sinister cowl turns out to be a “living creature.”

So far, so normal, but then there is … Borne.

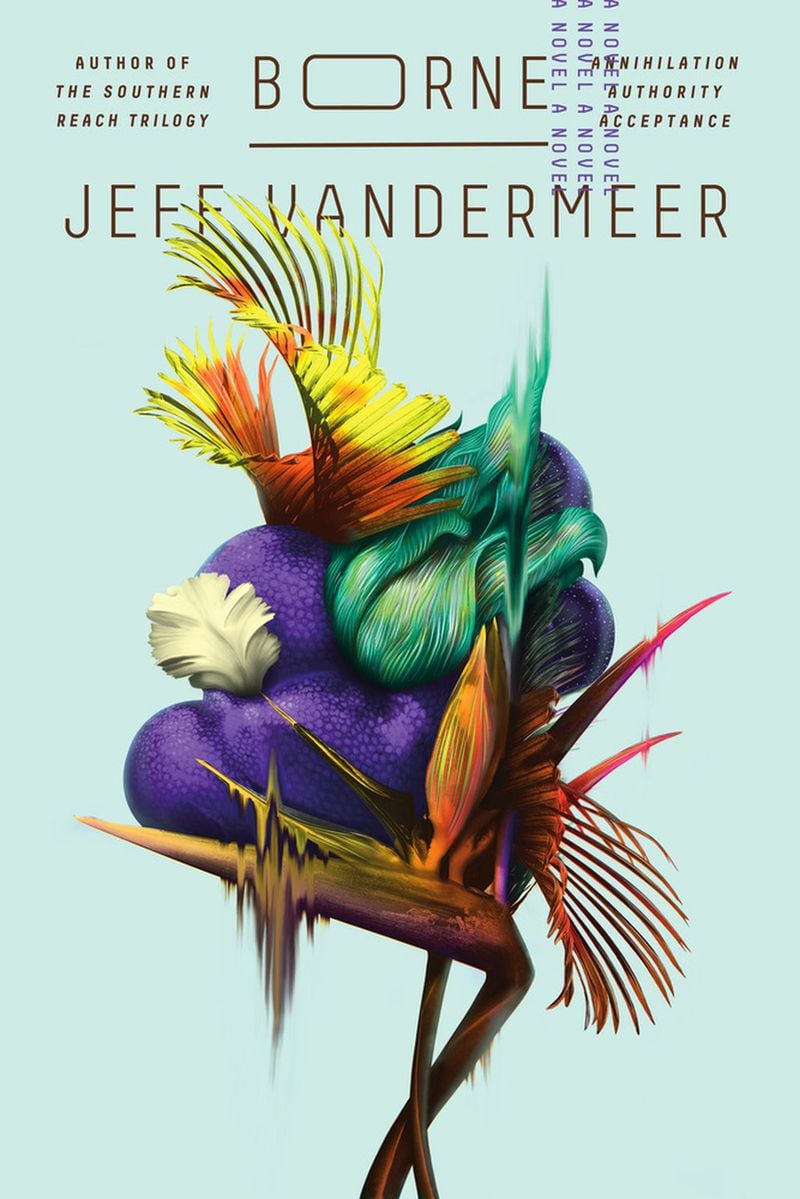

The latest creation of Tallahassee's innovative, Nebula Award-winning novelist JeffVanderMeer, Borne is an impish blob with consciousness — quite a bit of it, actually. He is invertebrate and metamorphic; he can shift his shape from "cone to square to globe." He can disguise himself as a rock or suddenly go flat in a Taoist defense stratagem, which he employs in the book's magnificent decisive clash.

Sometimes he looks like a sea anemone, just as he did when Rachel first snatched him off the furry haunch of Mord. At rest, however, he assumes an “upside-down vase design,” known as the “Borne Classic.” He pulses, strobes and changes colors like an expensive mood ring. He sprouts “feathery filaments” and is often circled by a “startling collection of eyes.”

Of course, he’s precocious — Borne has nine-senses, after all — and, under Rachel’s tutelage, he develops at astounding speed from an inquisitive child (“Why is water wet?”) to a rebellious teen roaming the city’s apocalyptic boulevards after dark. Cheerful and lovable, he becomes Rachel’s protector and companion. He’s also a killer, though for awhile Borne would argue his case to the contrary: “I don’t kill. I absorb. I sample. Digest. It is all alive. In me.”

Rachel, a suspect narrator, understands herself as much as she can. Sections of her life story are lost for a reason VanderMeer artfully conceals until the conclusion. Her explanations for the general collapse of civilization are vague: “rising seas,” cannibalistic warlords, and so forth.

Rachel outlines the dire situation with precision. It’s “Not so much a civil war between factions,” she says, “as a rising chaos.” The city’s poisonous river is a sick moat producing atmospheric chemical content that makes sunsets glow with the gold-leaf intensity of a Klimt painting. Lichen is omnipresent; trees are “half-fossilized”; infrequent calm seems “preternatural.”

The source of the city’s environmental contamination is clear: the mysterious and parasitical Company, now abandoned. Wick used to work there, building biotech like “Memory Beetles,” which crawl inside a person’s brain to remove traumatic memories or temporarily implant happy memories belonging to others.

To Rachel, the Company was like a colonial power that abused the native people and exploited the biotech it created, before discarding both: “They made us dependent on them. They had experimented on us. They had taken away our ability to govern ourselves.” The Company’s holding ponds and multiple levels produced Mord and the Magician — we’re not really sure how or why, but in VanderMeer’s universe, there’s always the approach of something unknowable and the realization that you’re going to get to know it, like it or not.

Can any benevolent force regain control and restore order? Between the vengeful Mord and the conniving Magician, it isn’t looking too good. With a “giant carious eye” like “an evil sun,” Mord desires to become “the God of Nothing”; he’s charismatic enough to inspire religious cults. Beagle-like, his vicious followers (“Mord proxies”) have “venomous breath that could set fire, given the right accelerant.”

Across town, The Magician makes her HQ in “the cracked skull of the observatory.” She directs a “medicated army” of mutants, some of whom have “traded their eyes for green-gold wasps that curled into their sockets and compounded their vision.”

Jeff VanderMeer has become a major force in speculative literature, advancing on multiple fronts. "Annihilation," the first volume of his much-lauded "Southern Reach Trilogy" (2014), is now a forthcoming film directed by Alex Garland, whose modish "Ex Machina" is well regarded in science fiction cenacles. "Borne" has been acquired by Scott Rudin and Paramount Pictures.

Though hardly without precedent in science fiction, VanderMeer raises fundamental philosophical questions of the existential sort: What does it mean to be “human”? Is so-called Artificial Intelligence entitled to the Rights of Man and of the Citizen? Does historical amnesia play a role in the creation of myth? What are the psychic consequences of the remote-control imperialism as represented by the Company?

While we follow Borne’s progression to his heroic destiny as a catalyst for profound change in the city, there’s also plenty of fun to be had throughout this charming globular epic. VanderMeer delivers the action scenes with a boyish mania. And his Homeric account of Japanese-style kaiju Armageddon is every thinking adult’s juvenile delight. Still, as the great monsters fall, “Borne” evokes that sense of sadness akin to the first cinematic experience of witnessing the demise of Godzilla at sea.

VanderMeer’s work is distinguished by the empathy he extends to the non-human — whatever such a designation may mean — and through Rachel eyes, the dying biotech reveal “their sad, delicate skeletons.” These creatures, she believes, must develop an ecological system of their own: “The story of the city will someday be their story, not ours.” Here we leave “Borne,” a seemingly hopeless tale with a happy ending, its aspirations undisguised, a peculiar object aloft someplace in the canopies of Earthen green, a masterwork of its kind simply because it must be so.

FICTION

‘Borne’

By Jeff VanderMeer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

336 pages, $26

About the Author