SAVANNAH -- Given the Confederate-themed discourse that has afflicted us over the last few weeks, the question of precisely what holds the South together has become a legitimate field of inquiry — if not a cause for concern.

Three horsemen carved on Stone Mountain aren’t the glue that binds us. They never have been. The scrap of fabric they fought under never held the answer, either.

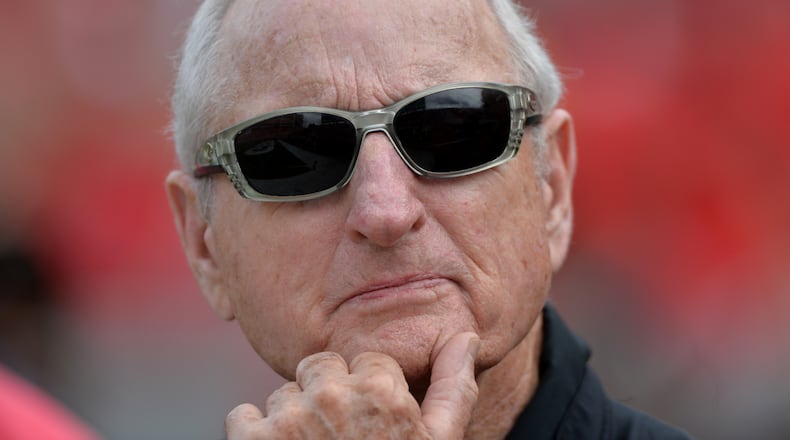

But Vince Dooley might.

On Tuesday morning, the former UGA coach and athletic director was the featured attraction at a coastal gathering of state lawmakers from the South, hosted by Georgia’s House Speaker David Ralston.

The breakfast session unfolded in a leisurely manner. A random table mate, a legislator from Fairfax, Va., was keen on a new book that attempts to explain what separates us from other beasts. It is our ability to create belief systems, he said.

Small groups of people can be bound by mere news, information and gossip, he had learned. Larger populations require larger thoughts to make them one: Religion, mythology, or a combination of both.

That’s a lot to take in before a second cup of coffee, but it was exactly the right frame of mind to be in when Dooley took the stage. He is coming up on 83 now, and no longer charges the stairs. He remains sharp, and is into writing books.

But for 40 years, as football coach and athletic director at the University of Georgia, he was in charge of one of the most powerful myth machines in the South – a machine that’s about to stir into another season.

We speak of football as a kind of religion in the South, precisely because of the way it binds us together. It is no coincidence that Secretary of State Brian Kemp has christened next year’s March 1 presidential preference vote, held concurrently in Georgia and several other Southern states, as “the SEC primary.”

On Tuesday morning, Dooley was the high priest who schooled his congregation in call-and-response.

For instance: When two come together, the correct greeting is "How 'bout them Dawgs?" The correct reply is "How 'bout them Dawgs."

Dooley read from ancient scripture. In 1892, Auburn footballers met Georgia and its goat mascot at Piedmont Park for the first time, and thus did Auburn smite them. “The alumni and students of Georgia were so depressed they barbecued the goat,” Dooley said, paving the way for the bulldog legend.

But there is a serious side to any myth machine. Dooley is a lifelong Southerner whose career arc coincided with decades of social upheaval, especially in the South.

He came to UGA in 1964, two years after the institution had formally desegregated, but before most public schools in Georgia had done the same.

When it came to integration, college football didn’t lead the way – it couldn’t, Dooley said in a private interview after his speech. The pipeline had to be created, and that was the job of Georgia’s high schools.

“In these little towns, even though they were initially pretty prejudiced, if a guy goes out on a football field and performs – they respect that,” Dooley said. “That unfolded over a four- or five-year period, then it all blended in with the colleges. The colleges then were much better prepared for integration.”

Dooley signed his first African-American scholarship players in the early 1970s. Running back Horace King was the standout, going on to play for the Detroit Lions. His mother was a custodian in one of the UGA dormitories.

Once African-American athletes were part of the scene, the question became how best to recruit them. And keep them. Under Dooley, UGA became one of the first Southern universities to begin the shedding of Confederate symbolism.

The Dixie Redcoat Marching Band became simply the Redcoat Marching Band. The song “Dixie” disappeared from its repertoire.

Dooley had a black staffer – a former member of the Atlanta Black Crackers baseball team – named Harry “Squab” Jones. “On racial issues, like ‘Dixie’ and so on, I would always seek his advice, privately. Usually I went along with whatever he said. He felt strongly about ‘Dixie,’” Dooley said.

But the coach knew to ask. “Maybe having a history background helped with that,” Dooley said.

What many forget about the football coach is that he earned a master’s degree in history from Auburn University in 1963. For his thesis, at the height of the civil rights movement, Dooley chose to dissect a Southern demagogue —Tom Heflin, a U.S. senator from Alabama in the 1920s who inveighed not just against blacks, but Catholics, too. And Dooley had graduated from a Catholic high school in Mobile, Ala.

Dooley ended his career as UGA’s athletic director in 2004, shortly after he performed a last political act. He joined Gov. Roy Barnes’ 2001 effort to remove the Confederate battle emblem on Georgia’s state flag.

“I was asked to make a few phone calls, which I did — knowing the background of how it got there,” Dooley said.

The Confederate myth machine hasn’t survived because it couldn’t adapt to the changing facts on the ground – specifically, the social equality of black Americans. Southern college football continues to unite us because it has adapted, however imperfectly.

And Dooley, master of the UGA myth machine, has been a major part of that.

About the Author