U.S. Supreme Court cases don't just happen. Often, they must be cultivated. They must be nurtured like any other hothouse flower.

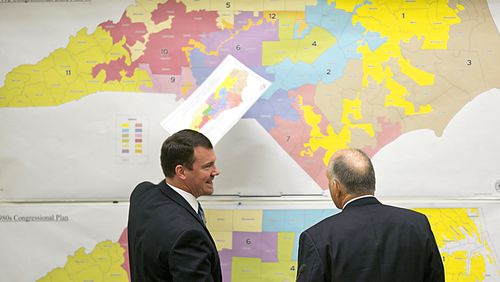

On Tuesday, a three-judge federal court panel ruled the congressional district map for North Carolina, a state equally divided between Republican and Democratic voters, to be unconstitutional. The judges said state GOP lawmakers had tried too hard to make sure that 10 of North Carolina’s 13 members of the U.S. House remain Republican.

If all goes as planned, the North Carolina case will be merged with two other redistricting cases. One from Wisconsin was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court late last year. Another from Maryland is scheduled for an airing in March.

Both are challenges to the practice of partisan gerrymandering, of drawing political boundaries to preserve a party’s position in power.

I say “planned,” because the North Carolina lawsuit and its arguments have roots in the Atlanta law firm of Bondurant Mixson & Elmore. Emmet Bondurant was one of the lead attorneys. But he also sits on the national board of Common Cause, one of three major plaintiffs in the action – along with the League of Women Voters and the North Carolina Democratic party.

“Everybody recognizes that gerrymandering is a huge problem,” Bondurant said in an interview this week. The disappearance of America’s political middle is often laid at its feet, as like and like are lumped ever more closely together. Republicans with Republicans, Democrats with Democrats.

Bondurant said Common Cause had already launched a writing competition in anticipation of the 2020 census and the redistricting that will follow, seeking new arguments against partisan gerrymandering.

The idea was to build on a concurring opinion written in 2004 by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the high court’s swing vote, in a dismissal of a challenge to Pennsylvania’s congressional map. While his conservative colleagues scoffed that one can’t remove politics from an inherently political process, Kennedy suggested that a red line might exist.

To that end, Kennedy also had a recommendation: Rather than challenging partisan gerrymandering under the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution, future plaintiffs might have better luck invoking the First Amendment.

In this light, gerrymandering is a matter of “viewpoint discrimination,” Bondurant said. Voters are being punished by the state with a form of exile, for ballots they have cast in the past.

But Common Cause and its lawyers had no need to wait for 2020 to test their theory.

In 2015, the Maryland case popped up. Democrats in power rigged the Sixth Congressional District to flip a historically GOP territory into their column. A First Amendment argument has been made there.

Then, in February 2016, a federal court in North Carolina ruled that state’s congressional map to be unconstitutional. Racial quotas had been used to improperly pack two districts with African-American voters.

“The North Carolina legislature got ticked off,” Bondurant said. Except that he didn’t use the word “ticked.”

The lawmakers quickly produced a substitute – which became the subject of Tuesday's ruling. The state's Republican legislative leadership hired a professional line-drawer – a fellow one liberal publication named a member of "the league of dangerous mapmakers."

North Carolina lawmakers publicly voted on the standards that would be used. Racial data was excluded. Census blocks would be graded on a formula that used statewide election results from 2008 to 2014 as a measure – except for the two presidential contests in which a fellow named Barack Obama was a candidate.

The lawmakers were also public about their object: Preservation of Republican dominance over U.S. House seats in their state. State Rep. David Lewis, co-chairman of the legislative committee, was a much-quoted man in the Tuesday decision. He reportedly said he proposed that the North Carolina map be drawn to guarantee 10 Republican members of Congress because he couldn’t figure out how to get to 11.

“I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country,” Lewis said.

Park that thought for a second.

Four constitutional arguments were made by Bondurant and his allies. The judges agreed with all of them.

Litigants leaned heavily on the First Amendment, as mentioned. And equal protection guarantees. Two other constitutional arguments were also made – that the North Carolina map violates Article 1, Sections 2 and 4, of the U.S. Constitution.

We’ll just deal with Section 2, which says: “The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States…”

This original portion of the Constitution was one of many compromises struck by the original framers. State legislatures would select U.S. senators (a practice now abandoned), but House members would be chosen by popular vote.

The federal judges picked up on this point – and that North Carolina lawmaker’s judgment that electing Republicans would be better for the country. “That is not a choice the Constitution allows legislative map-drawers to make,” the judges said. The core principle of republican government, they agreed, is “that the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.”

What happens next is a matter of speculation. The GOP-controlled North Carolina legislature will appeal the decision. The state’s Democratic governor has no say in the matter.

It’s possible that the current congressional map will remain in place through November, which means North Carolina voters will have been subjected to unconstitutional line-drawing in congressional contests since the 2010 census.

In 2016, Republican congressional candidates won 53 percent of the statewide vote, but retained – as planned -- 10 of 13 congressional districts. That’s a win rate of 76.92 percent. To gain a majority of North Carolina congressional seats under the current map in November, Democrats would have to cast 58 percent of the statewide vote, Bondurant estimated.

That could be important in a year in which Democrats are counting on an anti-Donald Trump backlash to regain control of at least one chamber in Congress.

Whether the North Carolina decision holds up could also have a tremendous impact on Georgia, once the 2020 census rolls through.

But there is a certain amount of risk in pushing an argument to its conclusion.

“This case is critical, and it’s intended to be that,” Bondurant said. “If the Supreme Court does not rule the North Carolina partisan gerrymandering unconstitutional, then there will never be a ruling that any partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional.

“You will never have a more perfect record or a clearer test case,” Bondurant said. Losing the case would give carte blanche to state legislatures, he admitted.

“It would mean an end to whatever restraint might currently exist,” he said.