Atlanta’s first Black superintendent got entire city involved in education

At their home in Compton, California, in the early 1970s, Alonzo Crim gathered his family members to ask them about a job opportunity.

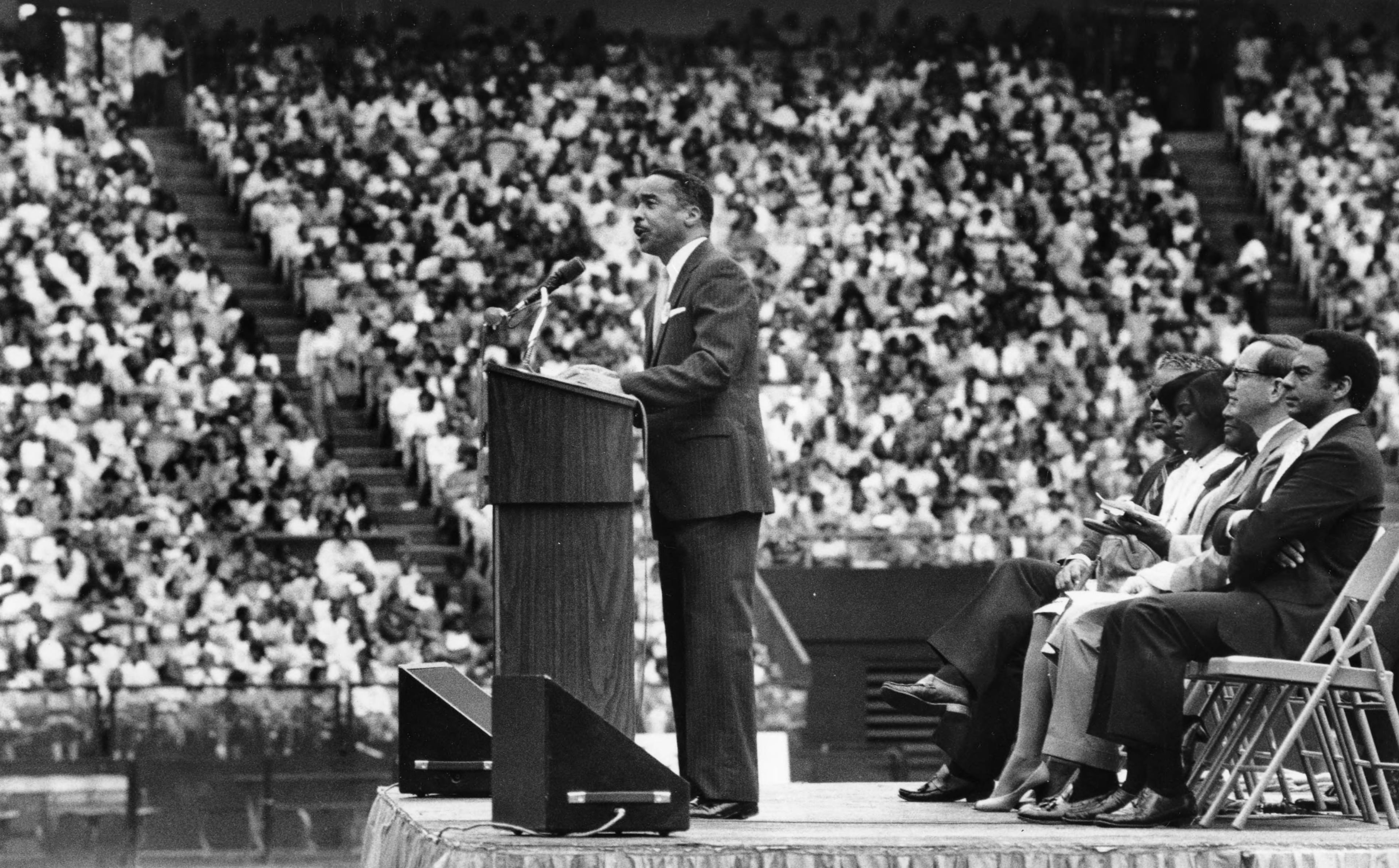

Atlanta Public Schools was calling. He was to be the first Black superintendent hired by a major Southern school system, as part of a court-ordered desegregation plan. He would be tasked with hiring a 50% Black administrative staff and integrating local schools.

But first, he had to check with his kids, Sharan, Susan and Timothy, and his wife, Gwendolyn. Sharan and Timothy Crim remember these family meetings as a regular event in their household — and as an example of their father’s leadership style as superintendent.

“I think the success that was produced in the school system was a lot because of who he was,” Timothy Crim told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “His whole idea was, ‘Let’s communicate with everybody. It doesn’t matter if people agree with you or disagree with you — let’s communicate and make people feel like they’re being heard, and treat everybody with dignity and respect.‘”

From that meeting, Crim and his family moved across the country so he could lead Atlanta Public Schools. By the time he retired in 1986, 15 years into the role, he would be the longest-tenured Black superintendent of schools in the country. The school system’s graduation rate was more than 70%, daily attendance exceeded 90% and students performed better than the national average in math and reading. About 90% of the school district’s students were Black.

Central to his success was an idea Crim wrote about and practiced: “A community of believers.” It’s the idea that for students to achieve, they must believe in themselves; for students to believe in themselves, adults must believe in them; and for adults to believe in them, the community must share the task.

“This community of believers gives us the opportunity to understand everyone has a part to play in contributing to educational excellence and opportunities for our children,” said Lawanda Cummings, the director of the Alonzo A. Crim Center for Urban Educational Excellence at Georgia State University. “Now it’s a part of the common lexicon, but clearly that has not always been the way that we thought about it.”

Crim had a way of making students feel as if they could do anything and believed there was a genius in every student, his children said. And he helped stakeholders citywide understand they had a responsibility to help students reach that potential.

Now 25 years after his death at the age of 71, educators still try to re-create the buy-in that Crim generated in Atlanta in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Through mentoring programs, partnerships with businesses and parent engagement efforts, the community of believers endures.

The values Crim practiced may be even more vital after the COVID-19 pandemic, when chronic absenteeism in schools has soared in Atlanta and across the nation, and students have faced academic setbacks and mental health challenges. And they may be more vital in the current political climate, where differing opinions can feel personal.

Crim went on to teach at Georgia State and Spelman College, where Sharan Crim said her father ended each class the same way — with a reminder: “None of us is as strong as all of us.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year’s AJC Black History Month series, marking its 10th year, focuses on the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and the overwhelming influence that has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout February in the paper and on AJC.com and AJC.com/news/atlanta-black-history.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.