Gwinnett gets tough on tots, merits of redshirting still up for debate

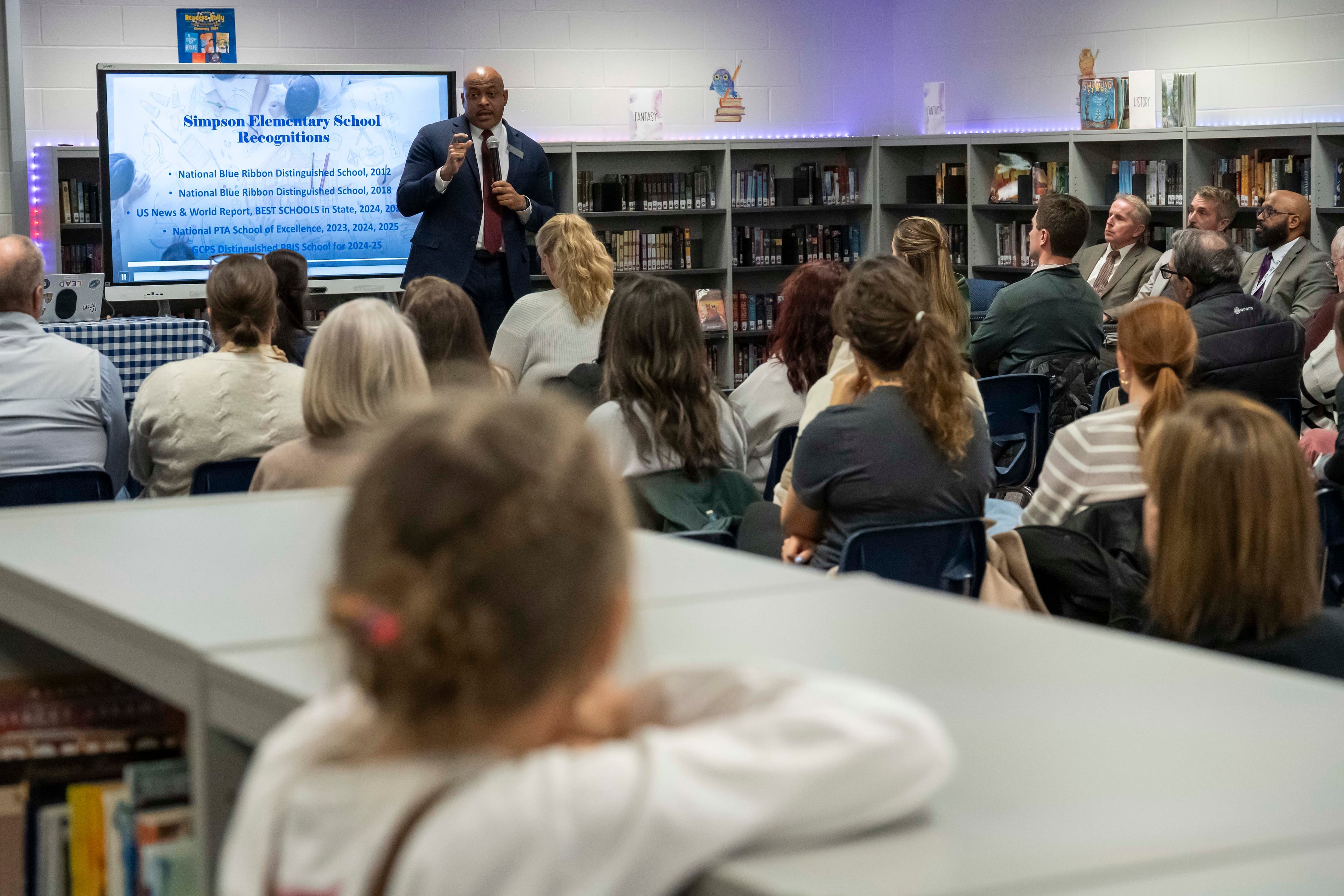

School officials in Gwinnett County recently announced that they would begin enforcing a state law requiring kindergarten students to be 5 years old by Sept. 1 to enroll.

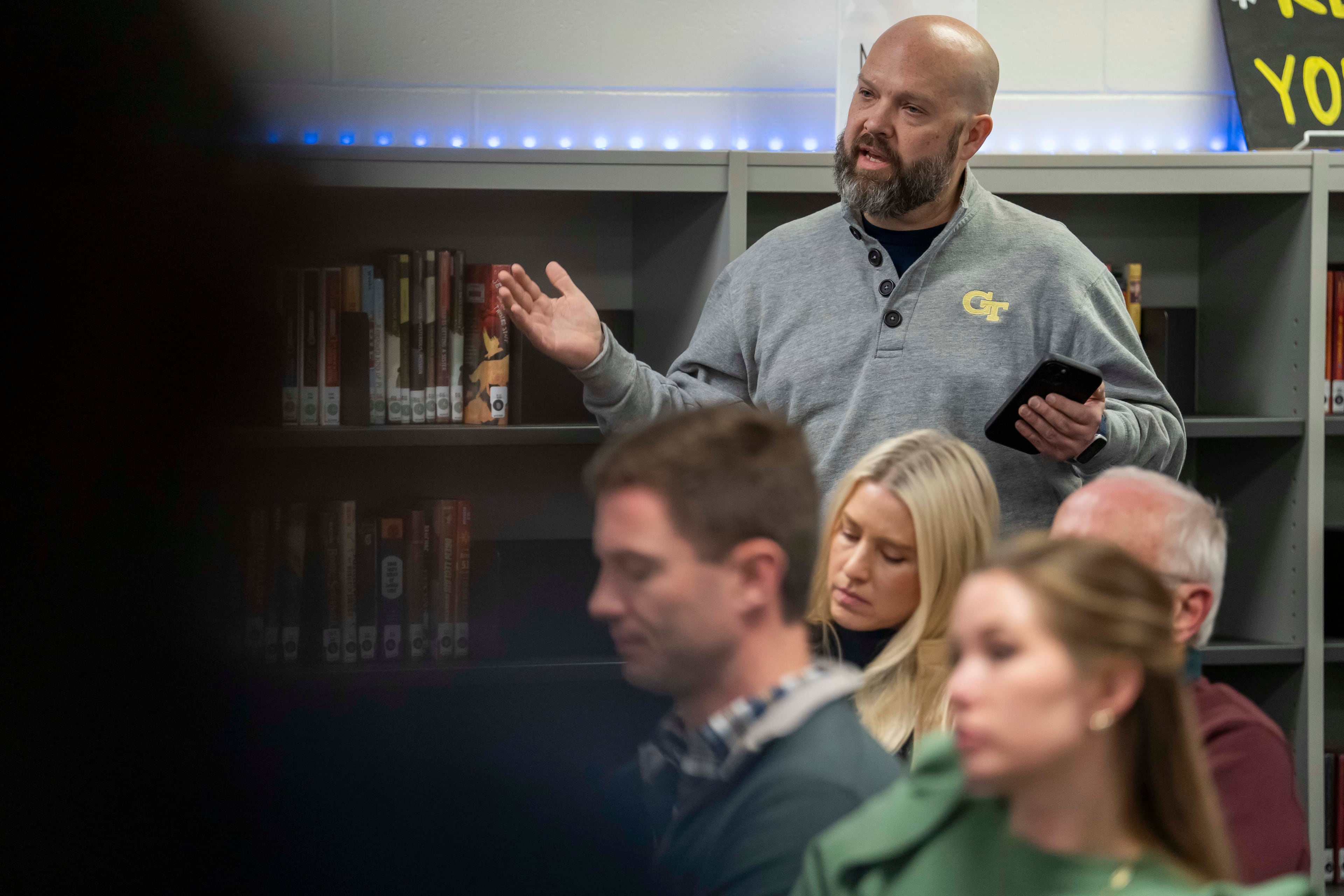

Some parents were upset that the crackdown has put the practice of redshirting, delaying kindergarten entry by one year, in question for the future.

More details on the updated process for grade level consideration will be shared with the community in early March, unless a state lawmaker can pass legislation that lets parents decide when their child can start kindergarten.

The new legislation, introduced by Rep. Scott Hilton, R-Peachtree Corners, is designed to target confusion over the rules of redshirting, but the rules in Georgia aren’t confusing. It’s uneven enforcement of the rules that has created this conundrum, raising issues of class and gender.

Malcolm Gladwell popularized the concept of redshirting when he made a case for it in his 2008 bestseller “Outliers.” Gladwell stated that a person’s age relative to his or her peers is a key predictor of future success.

But academics trace redshirting back to the 1980s when initiatives such as No Child Left Behind began shifting the focus of kindergarten from productive play to academic attainment. Our mindset about kindergarten changed.

By the 2000s, redshirting, which originated with college athletes who spent an extra year developing their skills, also applied to 5-year-olds at the beginning of their educational journey who were deemed physically, socially or emotionally unready for kindergarten.

The question of grade placement mostly applies to kids who have summer birthdays that fall just before Sept. 1, the cutoff date for kindergarten eligibility. If these children start kindergarten on time, they could be among the youngest — and often least developed — in their class.

I do believe that parents know their children best, and I think this is particularly true when children are experiencing developmental delays outside the normal range.

Researchers have found this circumstance, along with experiences of trauma, to be the most relevant circumstances to consider redshirting a child.

But many parents make decisions about redshirting purely to give their child a perceived future advantage over other kids in their grade. And this is where the practice gets complicated.

I dug through almost 20 years of research on redshirting, and only one thing was clear: It probably isn’t solving the problem that many parents hope it will solve.

Most kids are not redshirted. Data shows only about 6% of kindergarten students in the U.S. have delayed school entry, though those numbers may have increased since the pandemic.

Boys are far more likely than girls to be redshirted, largely because of parental concerns about physical and emotional maturity. While these early differences often fix themselves in later grades, it is accepted as common knowledge that boys mature more slowly than girls.

One proposal from author Richard Reeves to address what has become a significant achievement gap between young men and young women, particularly for working-class and Black boys, is to redshirt all boys. According to Reeves, once boys begin school, they almost immediately fall behind girls. Starting them a year later would give them better outcomes in life, he argued.

But there is also evidence that redshirting boys has contributed to stagnant high school and college completion rates rather than resolving them. Proponents of this school of thought said it is easier for boys who have been redshirted to drop out of school a year earlier than if they had started kindergarten at age 5.

So redshirting is apparently both the solution to and a possible cause of the achievement gap between school-age boys and girls.

That’s what I call inconclusive research.

It’s also worth noting that decisions about redshirting are made in the spring, when a child who seems emotionally or socially unprepared for kindergarten could make significant developmental leaps by fall, when school is in session. If parents had extra time to decide whether their child was ready for kindergarten, parents might make a different choice.

Or maybe the cutoff dates for kindergarten should be earlier, giving all incoming kids at least a few months’ experience at being a 5-year-old before starting elementary school.

Rates of redshirting are highest among college-educated parents, according to research from Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Stephanie Howard Larson. College graduates are twice as likely to redshirt their kids as high school graduates. Thus, redshirting is also considered a luxury, the domain of well-educated parents who can afford an additional year of preschool.

Schools also pay a cost for redshirting.

Part of the reason Gwinnett school officials want to enforce state law is to avoid a financial penalty. If a school district enrolls a child in kindergarten who is beyond the age cutoff, they do not receive funding for that child.

Hilton’s bill might address matters of parental choice and possibly school funding; it might even help some Gwinnett County parents avoid a confusing situation this school year, but it won’t resolve the underlying problem: There is still no definitive verdict on the merits of redshirting and how the practice may be helping or hurting our children.

Sign up to get my column sent straight to your inbox: ajc.com/newsletters/nedra-rhone-columnist