Voting Rights Act uses race merely to remedy proven racial discrimination

If the U. S. Supreme Court strikes down Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act after hearing oral arguments on Wednesday, it will surely devastate minority voting rights.

But it also will shatter three generations of anti-discrimination laws in America and void the 15th Amendment’s guarantee of equal voting rights by holding, in effect, that federal courts cannot consider race in remedying racial discrimination.

The court has asked parties in a Louisiana Congressional redistricting case to address only one question: “Whether the State’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the 14th or 15th Amendments to the U. S. Constitution.”

In plain words, is it unconstitutional to consider and use race for the purpose of remedying racial discrimination in voting by creating a majority Black district?

Repealing Act’s Section 2 would have ‘crushing’ consequences

First, it is vital to understand that this case is worlds apart from the 2023 decision in the Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard case, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts. That case held that colleges cannot consider race in implementing the institutions’ voluntary, self-determined goals of advancing more diversity and inclusion.

The Louisiana v. Callais case, by contrast, enforces the Voting Rights Act by providing a judicial remedy using race only after a federal court has made a fact-based finding of racial discrimination in voting. Then, and only then, does a court use race as a consideration in fashioning relief from the government’s discriminatory practice.

As a practical matter, it is impossible not to use race if a court is going to cure racial discrimination of any sort. For example, a judge must consider race under the Civil Rights Act in remedying a group of Black persons’ proven exclusion from government contracts.

The legal remedies for all federal and state anti-discrimination laws, the Voting Rights Act included, by necessity consider and use race in order to cure race discrimination.

To strike down the Act’s Section 2 because it uses race in fashioning a remedy would have crushing consequences for assuring equal opportunity of all sorts across the nation.

Almost all existing majority Black districts were created by states complying with court orders or court precedents as a result of the judiciary’s specific factual findings that government officials had violated the voting rights of Black citizens by drawing lines to assure that Black voters could not elect the candidates of their choice.

‘Racial entitlement’ claim is a mistaken argument

And during the last 40 years, it has been much harder for Black citizens to win a case of racial discrimination in voting under Section 2 than in most other lawsuits claiming racial discrimination. In 1986, the Supreme Court established the “Gingles test,” requiring plaintiffs to meet three factual conditions before federal courts can even consider whether the evidence proves that a district’s voting boundaries disadvantage Black citizens on account of race.

The three conditions are:

- A challenging minority group must be “sufficiently large and geographically compact” enough to constitute a voting majority in a district.

- A minority group must be “politically cohesive,” generally voting for the same or similar candidates as a community of interest.

- The majority group must be “politically cohesive,” routinely voting as a bloc to defeat the preferred candidates of the identifiable minority group.

If discrimination is proven afterward, federal courts usually let states restructure districts as they see fit so long as Black voters have an equal opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice. (This explains the bizarre shape of the proposed Louisiana district, which its legislature refused to make more compact for partisan reasons.)

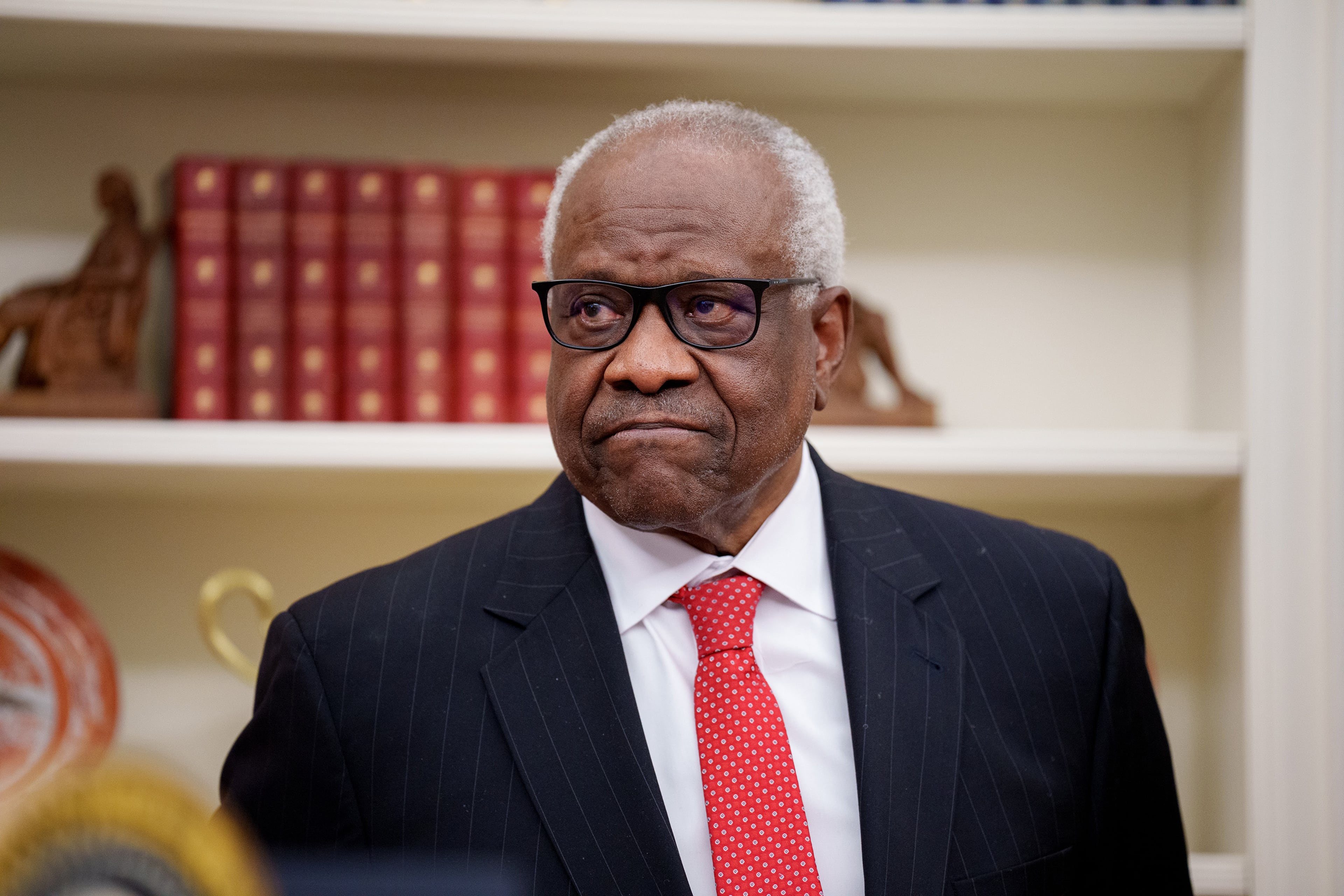

Often, government officials create one or two majority Black districts among a larger number of majority white districts. But that does not create, as Justice Clarence Thomas has mistakenly charged, a “racial entitlement,” as he wrote in his dissent in the 2023 Allen v. Milligan case on voting rights in Alabama, Instead, it enforces citizens’ entitlement of equal voting rights enforced by the Voting Rights Act and established by the Constitution’s 15th Amendment.

Justice Hugo Black created a road map for SCOTUS today

As a majority of self-described originalists, the justices would do well to remember the words of Justice Hugo Black of Alabama, perhaps the Court’s original, full-fledged originalist.

Concerning the 15th Amendment, Justice Black wrote in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966): “In addition to this unequivocal command to the States and the Federal Government that no citizen shall have his right to vote denied or abridged because of race or color, § 2 of the Amendment unmistakably gives Congress specific power to go further and pass appropriate legislation to protect this right to vote against any method of abridgment no matter how subtle.”

These words were written by a white southerner, born in 1886, only sixteen years after the 15th Amendment was ratified and instrumental in moving the Court to outlaw school segregation in 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) and to apply the Constitution to congressional redistricting. Black’s words are a timeless reminder that the Constitution gives Congress the power to enact and the Supreme Court a constitutional duty to uphold and enforce federal statutes that consider race to remedy racial discrimination in voting.

That is exactly what the Voting Rights Act does — nothing more, nothing less.

Steve Suitts has been involved in voting rights in the South for almost five decades. Today, he is an adjunct professor at Emory University and his most recent book is “A War of Sections: How Deep South Political Suppression Shaped Voting Rights in America.”