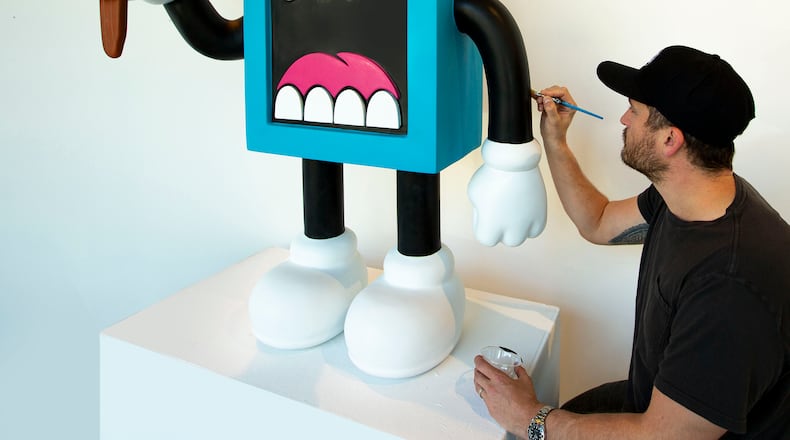

Wearing black jeans, graphic tattoos and a dusting of facial hair, Greg Mike looks every inch the street artist.

And though his most noted graffiti creation, “Larry Loudmouf,” with his Tide blue body and yawling open mouth, is a raging expression of cartoon id suggesting unbridled anarchy, Mike is strategic and controlled and tends to play things close to the vest.

While his chosen street art profession is more hustle than 9-to-5, Mike is cut from different cloth, an entrepreneur balancing the wilder tendencies of his art form with a knack for innovation and turning a passion into a business. It’s a drive he admits he’s had since childhood. As a preteen he created and singlehandedly ran a skateboarding zine. In college he co-founded the denim brand Carpe Denim — eventually living in China to oversee production manufacturing — and later ran the street fashion tradeshow TRAFIK.

Credit: Greg Mike

Credit: Greg Mike

“I got denied to all my dream art schools I applied to, which in turn only added fuel to my fire, which still motivates me to this day,” says Mike.

The evidence of Mike’s drive can be seen all over Atlanta: in a lobby mural inside Midtown’s Moxy Hotel, at Shaky Knees, in commissions for the Braves, Porsche and Coca-Cola and in the homes and offices of high-profile collectors including Dallas Austin, Diplo, Swizz Beatz, Scooter Braun and Justin Bieber.

An impresario of complex, multifaceted events, Mike has been organizing OuterSpace since 2015. The local, week-long festival of mural painting, music and skateboarding gives visual artists the same stage and hype as musical acts. And since 2009 he’s helmed ABV Agency and Gallery (ABV stands for “a better view”) where he connects street artists and brands like Jack Daniels, Red Bull and Toyota for collaborations.

Even his language is inflected with phrases that suggest someone able to convince a team of corporate decision makers that his ideas to “activate” a space with street art will help sell their product.

“I was always interested in the business aspect as much as the art aspect,” he admits.

And now, at age 40 with a wife and two children, ages 2 and 4, the Reynoldstown resident is expanding to an even bigger stage and hoping to turn a piece of highly visible real estate into part of his Atlanta legacy.

Credit: Greg Mike

Credit: Greg Mike

Purchased in 2021 for $875,000, Mike is transforming Holy Temple Deliverance Church in East Atlanta Village into a creative hub that he envisions as a combination work-art-event space big enough to possibly harness his many dreams and litany of projects under one roof.

On Instagram a swath of Atlanta’s creative class from Dallas Austin to artist Fahamu Pecou and co-founder of Black Women in Visual Art Lauren Jackson Harris offer Mike high-fives to the news, illustrating the depth and breadth of his connections formed over the 19 years Mike has lived in the city.

Designed by Kronberg Urbanists + Architects, the team behind West End’s Lee + White development and Grant Park Market, the repurposed Black Baptist church will be home to Mike’s staff of eight and feature an open, lofted 3,500-square-foot gallery space with 16-foot walls in gleaming contemporary art white.

Instead of work crammed together on a wall, it can be hung strategically with more white space between artworks and more opportunity for contemplation.

“It’s going to be nice to actually have space to hang art where people can view it how art is supposed to be viewed,” says Mike.

Outside, Mike’s going to paint it black, giving the building a Scandi-inspired charcoal facade. Seeing art as a higher calling and sharing a commonality with religion in the ability to bring people together, Mike intends for this temple of art to retain the church steeple and original marquee when it opens in summer 2023.

Credit: Greg Mike

Credit: Greg Mike

At more than 6,000 square feet, it’s a vast scaling up from Mike’s current 1,300-square-foot gallery and agency space in Studioplex, where size limited the type of artists he was able to exhibit. Now Mike can dream big and potentially reach out to favorite artists such as Argentine-Spanish neo-op graffiti artist Felipe Pantone and start featuring bigger, more ambitious sculptures, installations and paintings. With its reinforced concrete floor, Mike could drive a car into the space, not an unlikely event considering how often street artists are asked to customize one-of-a-kind art cars.

The space will feature climate-controlled art storage and a large space adjacent to the gallery where visiting artists can create installations.

“Finally, I have a space where I can do a giant sculpture. I can do a 15-foot sculpture. I can do a painting that’s 20 feet tall,” muses Mike. “I could do multiple experiences in these little side rooms.”

Mike’s savvy co-mingling of creativity and commercial success may come from his father, Bill Mensching, who has also blended art and business as the owner of Connecticut-based ShowMotion. The scenery fabrication business creates elaborate sets for Broadway shows like “Beetlejuice,” “Kinky Boots” and “Angels in America.”

Mike admits he grew up with cool parents who took him to Who concerts, encouraged his creativity and gave him plenty of examples of how to turn creative work into a living.

His father and brothers helped Mike create his own 3-D art production in 2015, a live art pyramid for Heineken during the Scope Art Fair in Miami. It was Mike’s idea to literally elevate artists the way he saw musicians being venerated and give graffiti artists a supersized platform, music, lasers, lights and a DJ as they stood on the pyramid making their art.

Credit: Greg Mike

Credit: Greg Mike

A photograph of the pyramid became the lead image in a New York Times feature on the infiltration of big-name brands into the art fair ecosystem.

Mike is pragmatic about bringing an art form once associated with renegade — often illegal — creativity defiantly produced outside the gallery space into an age far more comfortable with the blending of creativity and commerce.

Working as a kind of middleman, his ABV Agency allows street artists to make some coin beyond skateboard decks or public art commissions. And he’s well aware of how today’s advertisers need to be more strategic, more covert, in selling their products.

“I feel like brands have realized that traditional advertising isn’t working like it used to” says Mike. “I think with social media, consumers have become smarter. They want to see artists that they connect with, and they want to see a real collaboration.”

Though not every graffiti artist is down with it, choosing to tie your art-making to a brand is a matter of personal choice, says DC Murals Executive Director Cory Stowers, whose organization documents and preserves murals for future generations.

Credit: Greg Mike

Credit: Greg Mike

“You know, we have a band from Washington, D.C., a very legendary punk rock band Fugazi. Ian MacKaye said they weren’t going to give interviews with any company that had liquor ads or cigarette ads. So, I kind of use the Fugazi meter when I’m talking to clients, right: Do I feel like this is good for the community?”

For Mike, his sniff test is similar. “My whole ethos has always been, I won’t work with a brand that I don’t think it’s, like, in my lifestyle, right? If I’m gonna work with Coca-Cola, yeah, I use Coke products. I drink Coca-Cola products. I’m not going to do an ad with a cigarette company.”

Having been in Atlanta for two decades and watched the dramatic changes the city has undergone, Mike thinks it’s a great place to be an artist. Unlike New York or L.A., he says there are still plenty of businesses willing to lend a wall for a mural, and fewer bureaucratic hurdles — there’s more of a pioneer spirit in Atlanta that has allowed him to grow his street art empire.

And like Karen Anderson’s Tiny Doors or R. Land’s “Pray for Atlanta” hands, Mike’s Larry Loudmouf has become synonymous with Atlanta’s urban landscape.

Meanwhile, Mike maintains that his sprawling art complex is not his finale. Like any savvy businessman, he’s still conceptualizing a 10-year plan and what he’ll be doing at 50, because Mike is interested in his legacy and doing more things that will allow him to leave his mark on the city he’s grown to love.

“This is not the end,” he says. “This is not the culmination.”