Adding the African-American experience to a Confederate memorial

So the idea of placing a bell tower atop Stone Mountain in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. has been set aside for the moment.

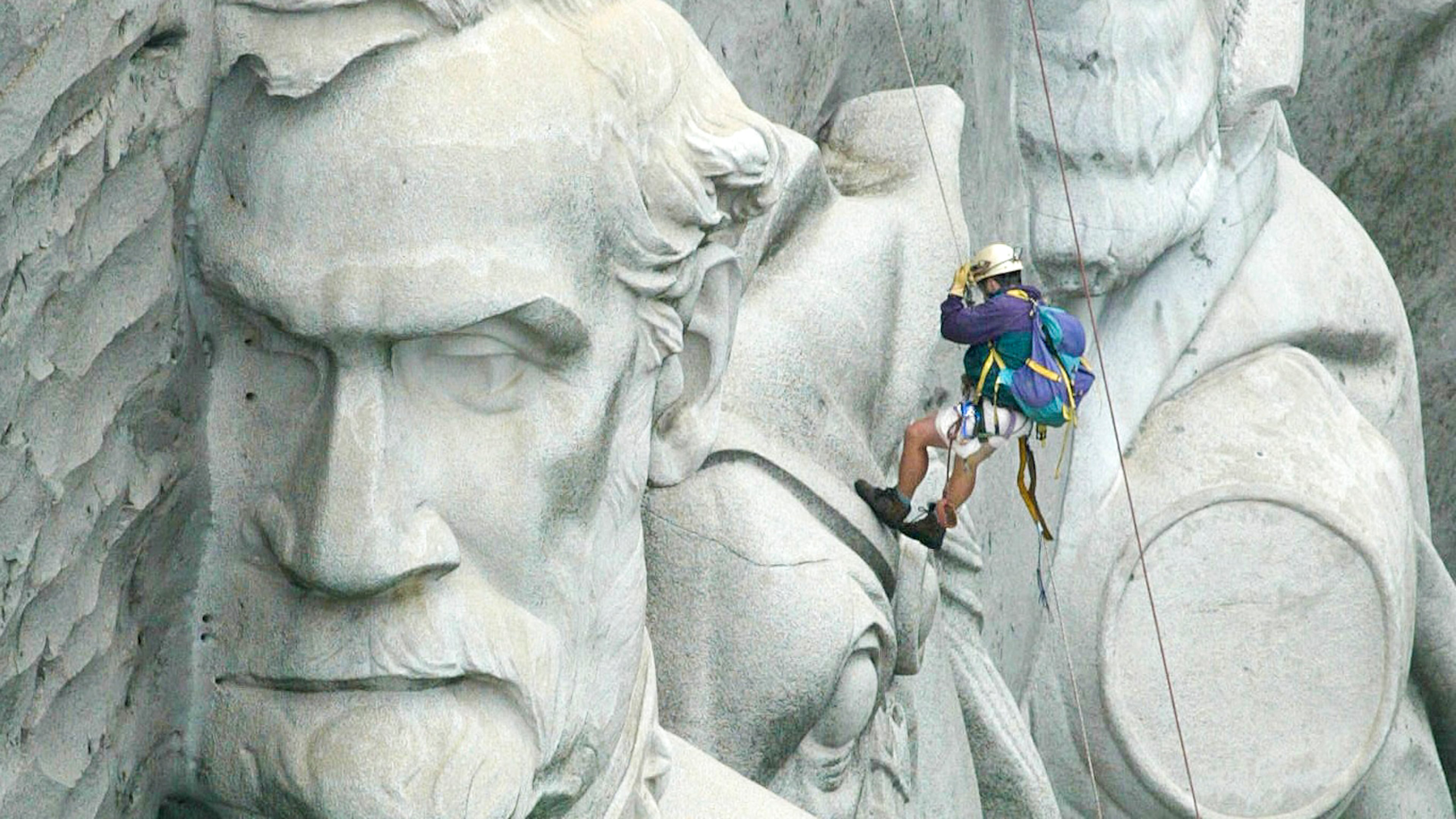

Instead, the caretakers of the state’s largest granite-based tourist attraction will attempt something that may be even more delicate: A museum exhibit that will tell the story of African-American soldiery during the Civil War, perhaps under the carved stone gazes of three Confederate heroes who fought to keep slavery alive.

For the largest part of the last 150 years, control of the Confederate story has served as the foundation of white Southern culture. Admitting new players into the narrative circle, if done honestly and well, poses a far bigger threat to hardcore enthusiasts of the Lost Cause than tearing down a simple piece of cloth.

Or raising a bell tower.

The scope and content of the exhibit will be hammered out over the next year. An entirely quiet discussion is unlikely. Ownership of history is one of most valuable prizes any society has to offer.

The Tuesday decision by the board of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association to proceed with the effort was unanimous. “It’s a story that’s of historical interest and one that needs to be told,” said CEO Bill Stephens.

Let it be noted that this is a Republican attempt to do the right thing. Stephens is a former GOP state senator. Board chairman Carolyn Meadows is also a board member of the National Rifle Association. The motion to proceed was made by Scott Johnson, who serves as 11th District chair of the Ted Cruz presidential campaign.

The only active Democrat involved in the proceedings was Michael Thurmond, the former state labor commissioner and DeKalb County school superintendent. An African-American, as well as a now-and-then historian, he was there to cheer them on.

Such a museum would be a “phenomenal addition,” Thurmond said. More than 200,000 black men fought for the Union during the war, he told board members. Ninety percent of them were Southerners – former slaves.

“Tens of millions of slaves supported the Confederate war effort, a vast army that worked in arsenals and mines and on plantations,” said Thurmond, author of two books that touch on the topic. “Most of this has been missed and under-appreciated and under-noted.”

Stephens, the CEO of the memorial association, said he would rely on Georgia academics and historians to help keep the effort from running aground. No doubt the Sons of Confederate Veterans will have a seat at the table. Thurmond would be a natural choice to make the effort bipartisan.

One obvious topic likely to spark debate: “Not everyone is aware of the fact that there were African-Americans who fought on the side of the South,” said Meadows, the board chairman. She said she is hunting up the video of a 1925 reunion of Rebel soldiers which she said shows African-Americans in uniform.

The presence of black Southern soldiers in numbers of any significance is highly disputed by many, many Civil War historians.

Yankee forces began admitting African-Americans to their enlisted ranks shortly after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Confederacy repeatedly refused to trade black military service for freedom – until it was far too late to make a difference.

“A slave by definition can’t volunteer. Black slaves were forced to directed and do many things on behalf of the Confederacy,” Thurmond said. “The real question is, were they there voluntarily, or were they there under the command and control of their owners? There are pictures of blacks in Confederate uniform, but they were slaves.”

Another pothole: The question of atrocities. Whether captured black soldiers should be treated as slaves in revolt or as protected prisoners of war remained an open question among Confederate forces throughout the conflict.

One example is the Fort Pillow massacre, an 1864 battle in Tennessee in which overwhelmed black troops attempting to surrender were, according to Union witnesses, simply shot. Should a Stone Mountain exhibit tell that story? I asked Thurmond after Tuesday's meeting was done.

Absolutely, he said. “You follow the facts. History should be based on facts,” Thurmond said. “That’s why we need to engage historians who are far more prominent than myself. Let’s look at the facts and let the facts speak for themselves. Who could be opposed to that?”

Thurmond’s question is the key to this project. Facts are powerful things. Some might even call them corrosive, when applied to carved objects of veneration.