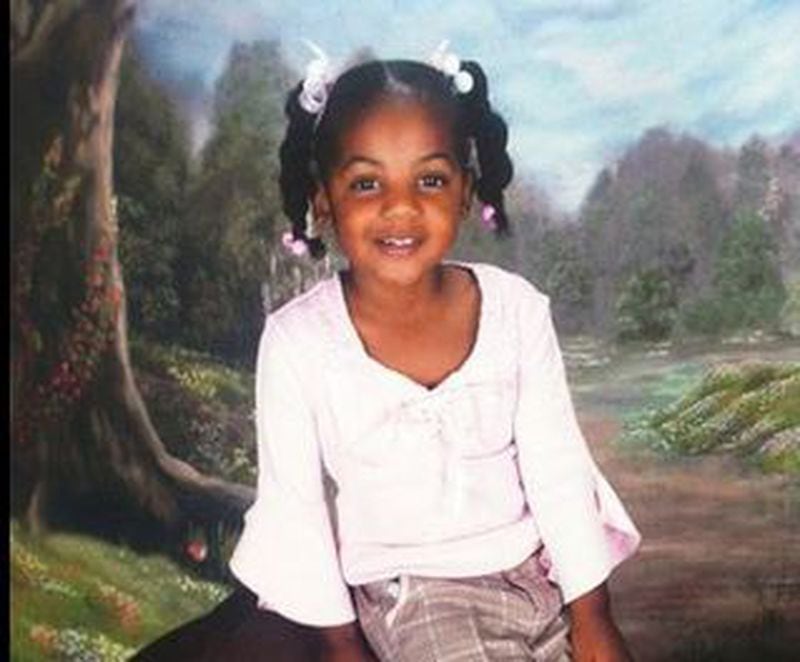

A 10-year-old Gwinnett County girl’s death of apparent starvation could have been prevented had Georgia’s child protection agency thoroughly investigated repeated complaints about the girl’s abuse and neglect, a lawsuit contends.

The suit was recently filed by the grandmother of Emani Moss, whose emaciated, burned body was found in a trash bin outside her Lawrenceville home in November 2013.

Emani suffered “constant abuse and deprivation from 2008 until her untimely death,” the suit said. A proper Division of Family and Children Services investigation “more likely than not would have prevented Emani’s deprivation and murder.”

Emani's father, Eman Moss, pleaded guilty in 2015 to his role in his daughter's death and was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. In a plea deal, he agreed to testify against Emani's stepmother Tiffany Moss, who is facing the death penalty.

Saying it's God's will, Tiffany Moss is acting as her own lawyer. Her case was scheduled to go to trial this month, but it has been delayed while the state Supreme Court reviews a Gwinnett County judge's decision to allow Moss to represent herself.

Emani weighed just 32 pounds when she died, authorities said. Her grandmother, Robin Moss, acting as the administrator of Emani’s estate, filed the suit against DFCS in Gwinnett County State Court. DFCS has no comment on the litigation, spokesman Walter Jones said.

The lawsuit seeks unspecified damages for the pain and suffering endured by Emani during her life and the “full value of the economic and non-economic value of her life had she lived.”

According to the suit, if child protection workers had acted on any number of red flags they could have made sure Emani was in a safe environment at her home or placed in foster care.

But in 2010, Cooper Elementary School staff contacted the police after Emani, then 6 years old, said she was afraid to go home with a bad report card, the suit said. Police later found welts, scrapes and bruises on Emani’s arms, chest, back and leg from being beaten with a broken belt.

Emani was temporarily removed from the home and Tiffany Moss eventually pleaded guilty to child cruelty. She was sentenced to five years on probation, and she and Eman Moss took parenting classes, the suit said.

But more problems arose in May 2012 when school employees reported to DFCS that Emani was suffering from emotional and psychological neglect. They also said Tiffany Moss had allegedly hit her stepdaughter on her back and her head with a belt because she was eating breakfast so slowly she was going to miss the bus. Emani saw the school nurse and was given an ice pack to put on her back, the suit said.

In response, DFCS opened an investigation, and a case worker spoke to Emani, Tiffany Moss and Emani's teacher, the suit said. But DFCS found "no maltreatment alleged" and attributed Emani's injuries to corporal punishment, the suit said.

On Aug. 6, 2013, just months before Emani's death, DFCS received an anonymous call from a person who said Emani was being neglected and appeared to be thin, the suit said. But the child welfare agency conducted no follow-up and made no visit to Emani's home after getting the tip, the suit said. Among the reasons listed for dismissing the complaint: DFCS didn't know where the Mosses were living.

In 2016, after looking into what happened in Emani's case, DFCS announced it was changing the way it assesses maltreatment reports.

Agency workers are to no longer decide whether reports like the one involving Emani in 2012 warrant investigations based solely on information gathered over the telephone. And no case is to be assigned a less-serious, lower-priority status until a caseworker meets a child who allegedly has been victimized, then-DFCS Director Bobby Cagle said.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/P7DYBH6TO7FEKG4SUXQQKADRXE.jpg)