This story was originally published in The Atlanta Constitution and The Atlanta Journal on April 26, 1984.

In Columbus on this day, children gather wildflowers and place them in urns beside the graves of the Confederate dead while tiny red-and-blue flags of a nation that never was wave over the markers of lingering defeat.

What is honored on Confederate Memorial Day in eight Deep South states is not so much a cause as the memory of what it cost.

Mrs. Dalton W. Taylor's great-great-grandfather died at Vicksburg, and Mrs. E.T. Johnson remembers her aunts talking about the skirmishes they saw from their front porch when some of Gen. William T. Sherman's union troops strayed into the fringes of Richmond County where she grew up.

'Both my grandfathers were in the Confederate Army, ' says Mrs. Johnson, who now lives in Atlanta. 'It is part of my family heritage. I was surrounded with all of this all of my life.'

Despite the trappings of Sun Belt wealth and the decline of racial strife, the heritage of the divisive Civil War is inescapable in the Deep South, where every little town seems to have its Confederate monument and where deep rows of tombstones mark the casualties.

In terms of lives lost, the Civil War was America's most costly war. On the Union side, 364,511 soldiers died of wounds or disease, and on the Confederate side, another 133,821 men died. Combined, the 498,332 fatalities surpass the 407,316 of World War II.

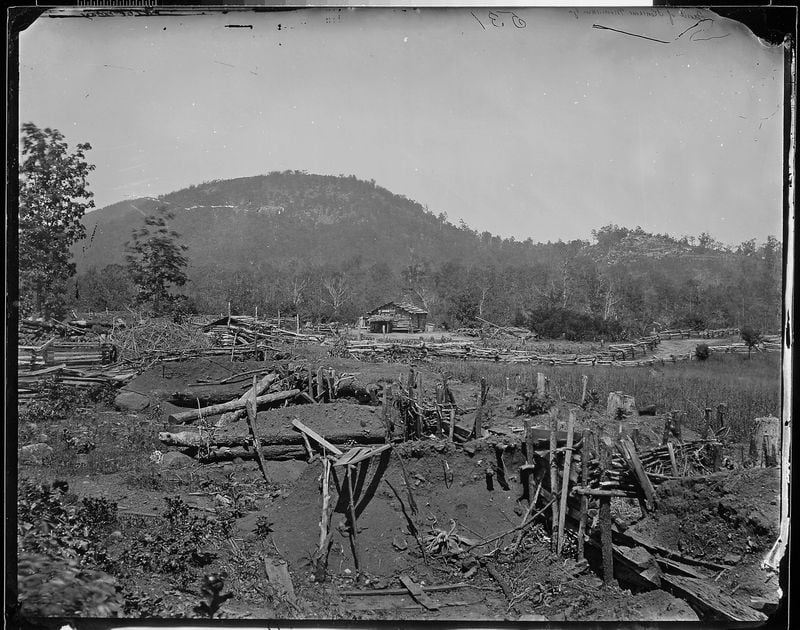

Georgia sent 125,000 troops into the war, and 25,000 died on the battlefield, more than from any other Confederate state, according to Steve Dykes, a spokesman for the secretary of state's office. Georgia also bore the brunt of Sherman's March to the Sea, which left a scorched path 40 miles wide through the state. When Atlanta fell in the summer of 1864, the Confederacy, for all practical purposes, fell with it, although the war lasted another year.

Few people today seem to believe the South should have won the war, but whether it could have won the war is debated endlessly by members of the Civil War Round Table in both the South and North. The honor of white Southerners who fought in the war is protected by a number of organizations, chief among them the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

While three of the original 11 Confederate states have dropped Confederate Memorial Day as a holiday, UDC has successfully turned back efforts in the others. In Georgia not long ago, powerful House Speaker Tom Murphy, who lost a grandfather in the Confederate cause at the Battle of New Hope, backed a plan to abolish the holiday because it costs the state an estimated $6 million a year. He lost.

Keepers of the tradition include people such as Raymond Reidcq, a World War II veteran who periodically dons his dress grays for memorial ceremonies as a member of the Old Guard Battalion of the Gate City Guard of Atlanta. The unit, which traces its beginnings to 1854 when it served as a kind of auxiliary police force, was the main one Atlanta sent into the Civil War.

Reid worries that interest in the war is waning. The Rhodes House in Atlanta, which the guard shared with a chapter of UDC for many years, has been taken over by the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation Inc., and Reid says the collection of Confederate weapons that he oversaw there is now scattered all over the metro area.

'Once we are passed and gone, who is going to keep up with the history?' asks Reid. 'It's history, you know. It actually happened. It's in the history books.'

Indeed, the Civil War is one of the two most important events in American history, insists Dennis Kelly, a transplanted Philadelphian who serves as historian at the Kennesaw Mountain Battlefield Park in Cobb County.

The other most important event, it is generally agreed, was the founding of the nation in the Revolutionary War. The Civil War saved the nation from a split that could have lingered until the present, Kelly says.

And he believes the South very well could have won the war because it believed so strongly that it would. That cockiness made defeat all the harder to bear, he contends.

'The South entered the war filled with self-confidence, ' he says. 'When it lost, it was a psychological blow. It was something participants carried to the grave and passed on to their children and their grandchildren.'

'Southerners are different from Northerners, ' agrees Mrs. Taylor, president of the Lizzie Rutherford Chapter of the Columbus UDC. 'I don't know that the war was more meaningful to us. Maybe. But our roots mean a lot to us. Our heritage means a lot.'

Ironically, the TV movie from Alex Haley's book 'Roots' about slave families seems to have enhanced interest in tracing Civil War heritage.

The State Archives gets about 200 letters a month from people wanting to find out if any of their ancestors have Confederate ties, and scores more visit the archives to pore over records. 'We really get an increase when something like 'Roots' is on TV, ' says Charlotte Ray, a Civil War specialist at the archives.

Mrs. Louise Hiss, who co-chairs the Georgia Division Headquarters of UDC, keeps tabs on thousands of records mostly tracing family ties to Confederate veterans now stored in a building at Stone Mountain Memorial Park. She says the number of UDC chapters in the state has grown steadily to 67.

In Columbus, Mrs. Taylor helps oversee the operation of the James W. Woodruff Confederate Naval Museum, which has the remains of two Confederate ships and an assortment of maritime memorabilia of the period gathered primarily from the nearby Chattahoochee River. Columbus was the site of a factory that made boat engines for the Confederate Navy.

Kelly says the Kennesaw park draws scores of visitors who study the war for a living and many more who are military hobbyists or relic collectors hoping to turn up some item of a cherished past.

More than a million arms were used in the Civil War, and most of them were recovered intact and placed in various collections, according to John Sexton, who runs a Civil War relic shop in Stone Mountain.

At the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park alone, there are 355 rifles, muskets and shotguns from the war on display. The park also has 264 cannons. Kennesaw park has another 200 cannons. And few Southern towns are without a cannon of their own.

Collectors using metal detectors routinely turn up buried Confederate and union belt buckles, buttons, bullets and cannonballs.

Diaries and letters occasionally show up in some unexplored attic. A cache of undelivered medals was found in West Virginia not long ago. And grave sites are discovered from time to time, especially in the South, where much of the fighting took place and where Confederate casualty records were haphazard at best.

Mrs. Lucille Lane, director of the Children of the Confederacy division of the Alfred Holt Colquitt chapter of the UDC in Atlanta, regularly takes young people on tours of the Kennesaw battlefield and, once a year, leads them on a camp-out at Andersonville, site of a prisoner-of-war camp where thousands of Union soldiers died.

'Many people think we are still fighting the war. I think that's pretty trite, ' says Mrs. Lane, noting that the Children of the Confederacy are involved primarily in helping to clean Confederate cemeteries, awarding scholarships for college studies and attending 'living history' exhibitions at various parks.

But Kelly says rehashing the Civil War offers an opportunity for some good-natured rivalry on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line.

'It is our war. We can pick sides, and we can curse the other side. I think it is good for the nation as a whole, ' he says.

The Civil War, he says, was the last man vs. man war before technology made warfare machine vs. machine. 'In the Civil War, in a sense, we still had the knights, ' he says.

It was with that sense that Mary Williams, a Confederate widow, and her daughter took wildflowers to the graves of soldiers in Columbus in what is purported to be the beginnings of the Confederate Memorial Day tradition.

In a letter to a Columbus newspaper, Mrs. Williams once wrote:

'We cannot raise monumental shafts and inscribe thereon their many deeds of heroism, but we can keep alive the memory of the debt we owe them by dedicating at least one day in each year to embellishing their humble graves with flowers.'

About the Author