In a searing decision, a judge in Columbus has granted a new trial to a man convicted of rape and murder 43 years ago based on new DNA evidence, at the same time condemning "undeniable" race discrimination during jury selection by the prosecution.

The ruling by Senior Muscogee County Superior Court Judge John Allen overturns the convictions against Johnny Lee Gates, who was sent to death row for the 1976 rape and murder of Katrina Wright. Wright was a 19-year-old German immigrant who had moved to Columbus just 12 days earlier to be with her husband, a soldier at Fort Benning.

“We are grateful to the court for recognizing the evidence of Mr. Gates’ innocence, and for taking this important step towards justice,” Clare Gilbert, executive director of the Georgia Innocence Project, said. Her office and lawyers for the Southern Center for Human Rights represented Gates in his bid for a new trial.

Muscogee County District Attorney Julia Slater did not return a phone call or email message seeking comment.

Gates, who was re-sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in 2003, challenged his convictions based on new DNA evidence and the discovery of prosecutors' notes that disparaged prospective African-American jurors for his trial. In his ruling, Allen granted the new trial based on the DNA evidence, but not because of race discrimination during jury selection — although he was unsparing in his criticism of such conduct.

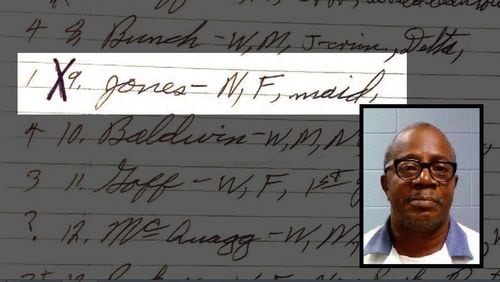

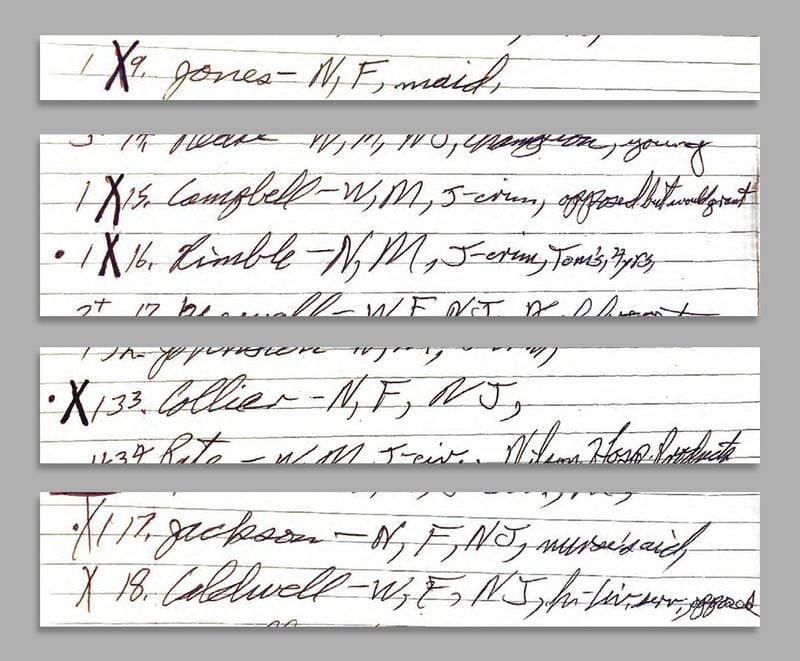

“The prosecutors clearly engaged in systematic exclusion of blacks during jury selection in this case,” Allen wrote in a Jan. 10 decision. “They identified the black prospective jurors by race in their jury selection notes, singled them out … and struck them to try Gates before an all-white jury.”

The prosecutors' notes labeled prospective white jurors with a "W" and black jurors with an "N." Prosecutors also described some prospective black jurors as "slow," "old + ignorant," "cocky," "con artist," "hostile" and "fat."

Jurors were also ranked on a scale of 1 to 5, and all black jurors were given a “1.” The only one of the 43 prospective white jurors who got a “1” said he was opposed to the death penalty, Allen noted.

“Taken together, the notes demonstrate a purposeful and deliberate strategy to exclude black citizens and obtain all-white juries,” Allen said.

Moreover, the judge said, Muscogee County prosecutors’ strikes employed in seven death penalty trials from 1975 to 1979 confirm the discrimination. In six of those seven cases, prosecutors removed every potential African-American juror to secure all-white juries. In the seventh case, an all-white jury was impossible because the prosecution did not have enough strikes to get rid of all the black jurors, Allen wrote. On top of that, prosecutors “used racially charged arguments to the all-white juries they secured.”

Allen concluded: “The evidence of discriminatory intent is overwhelming.”

If Gates’ lawyers had raised such a claim much earlier, it is likely they would have prevailed. But because they didn’t, Allen said he had to rule against them on that claim.

One requirement for obtaining a new trial is for a defendant to show he was diligent in bringing his claims without undue delay. Because Gates could not give a reasonable explanation why he didn’t bring his race discrimination claims sooner than decades after his trial, he cannot get a new trial on that ground, Allen said.

But Allen found that was not an issue with the new DNA evidence.

During the trial, prosecutors said the killer took $480 in cash from Wright, the murder victim who suffered a fatal gunshot wound to her head. A state investigator testified that the killer tied a bathrobe belt “very, very tightly” around Wright’s hands and double-knotted the belt. A necktie was also tied around the victim’s hands, with knots binding it together.

But during a hearing last year, Gates’ legal team presented the testimony of DNA expert Mark Perlin. He said Gates’ DNA was not found on the necktie or the bathrobe belt.

“The exclusion of Gates’ profile to the DNA on the two items is material and may be considered exculpatory,” Allen said. “Therefore, Gates is entitled to a new trial.”

Allen noted that the state called on two GBI scientists “who did not contradict, but instead supported, Dr. Perlin’s testimony.”

Allen also found Perlin to be a credible and qualified witness, and he noted that, under the circumstances, the three experts shared a distinct connection. “This was the rare hearing in which the scientist who trained the GBI scientists testified on behalf of the defense,” the judge said.

THE FIGHT FOR A NEW TRIAL

Lawyers from the Georgia Innocence Project and Southern Center for Human Rights have long sought to get a new trial for Johnny Lee Gates. In a motion filed last year, the lawyers noted that Columbus prosecutors had struck all prospective black jurors in six of seven death-penalty trials — including Gates’ — from 1975 to 1979. In the other trial, prosecutors couldn’t get an all-white jury because they didn’t have enough strikes to get rid of all the black jurors. A Georgia Tech mathematics professor found that the probability that black jurors were removed for race-neutral reasons was 0.000000000000000000000000000004 percent.

About the Author