This is a running account of the Justin Ross Harris murder trial. Harris stands accused of intentionally leaving his 22-month-old son, Cooper, in a hot SUV to die on June 18, 2014.

After five weeks of testimony and dozens of witnesses, the prosecution and defense are making their closing arguments today.

Court has concluded for the day. The trial is scheduled to resume around 8:30 a.m. tomorrow when Staley Clark will release the jury for deliberations.

The jurors are being sent home for the day.

The jury has been sent to the deliberation room.

The verdict, whatever it is, must be unanimous, Staley Clark said.

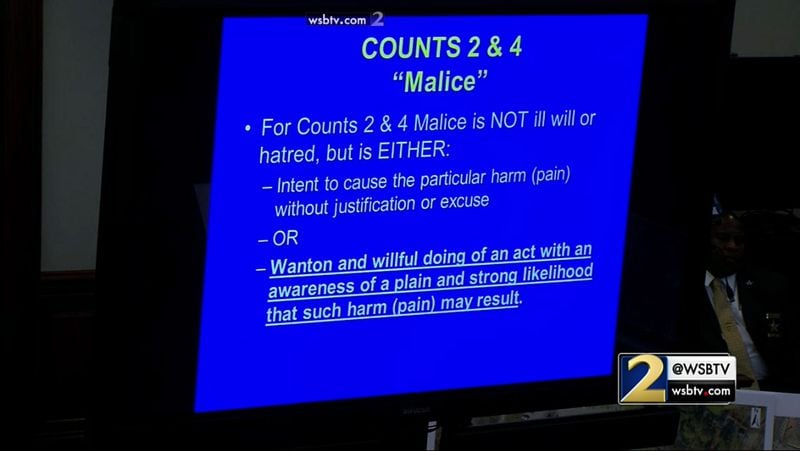

These are the charges against Harris:

Count 1: Malice murder

Count 2: Felony murder (caused Cooper's death while committing cruelty to children in the first degree – with malice, left Cooper alone in a hot car)

Count 3: Felony murder (caused Cooper's death while committing cruelty to children in the second degree – with criminal negligence, caused Cooper's death by leaving him alone in a hot car)

Count 4: Cruelty to children in the first degree

Count 5: Cruelty to children in the second degree

Count 6: Criminal attempt to commit the crime of sexual exploitation of children – that is, Harris asking a girl under the age of 18 to send him a nude photo of her genital area

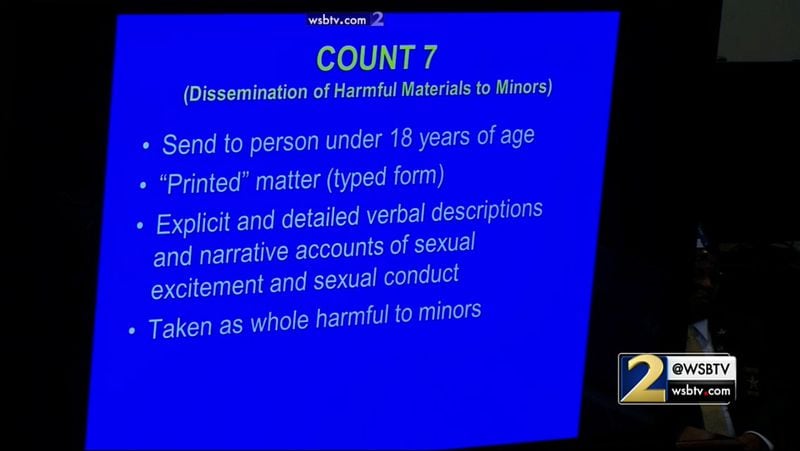

Count 7: Dissemination of harmful material to minors – sending a girl under age 18 a message "containing explicit and detailed verbal descriptions and narrative accounts of sexual excitement and sexual conduct"

Staley Clark is explaining to the jury each of the eight counts Harris faces.

To constitute murder, the homicide must have been committed with murder – the unlawful intention to kill without justification, excuse or mitigation. Georgia law does not require premeditation and no length of time to develop malice is necessary.

“Malice may be formed in a moment,” Staley Clark said.

Motive is also not required to find someone guilty of murder.

An accident is an event takes place without foresight or expectation. If the evidence shows Cooper’s death as a result of misfortune or accident and not a criminal undertaking or criminal negligence, the jury must acquit.

Criminal negligence is the willful wanton or reckless disregard for others who may reasonably expected to be harmed by the defendant’s actions. Even if not convicted of malice murder, a murder verdict based on criminal negligence could still carry a sentence of decades to a lifetime in prison.

Apply common sense and reason to decide the credibility of the testimony of any given witness, she said. The testimony of a single witness if believed is sufficient to establish a fact.

The defendant does not testify and if he doesn’t you can consider that in any way in making your decision, Staley Clark said. Harris chose on Friday not to testify.

You must decide for yourself whether to rely on a witness’ testimony, Staley Clark said.

If there’s just grave suspicion of the defendant, that’s not enough.

Harris is presumed evidence until proven guilty, Staley Clark told the jury. The burden of proof rests on the state to prove every element of the charges beyond a reasonable doubt.

A reasonable doubt means just what it says, a doubt of a fair minded impartial juror who is honestly seeking the truth, she said. It’s based on common sense.

“If you find your minds are waver, unsettled or unsatisfied, that is a doubt of the law and you must acquit the defendant,” she said.

Staley Clark is reading the full indictment to the jury.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Court is back in session.

Superior Court Judge Mary Staley Clark is now giving the jury instructions on how to interpret the law in their deliberations.

Closing arguments have concluded. The court is taking a break.

We’ve heard a lot in this case about word play, arguing over legal terms, some jawing back and forth between the defense and prosecution, Boring said.

“Right here right now, let’s get back to what this case is about. This case is about justice and it’s about that little boy, Cooper Harris,” he said.

Today that little boy would be 4 years old in pre-K, maybe learning how to play t-ball, Boring said. “But he’s not. He’s not here with us because that defendant took him. That defendant took his life for his own selfish, obsessed reasons.”

There have been a lot of excuses for Harris, “but who is going to speak for Cooper?” Boring said.

We can’t bring Cooper back but we can give him justice, Boring said.

“Justice in this case is a verdict of guilty. Justice in this case is holding the defendant responsible.”

There were plenty of triggers that should have reminded Harris that Cooper was in the car, Boring said.

For instance, Leanna asked via text if he got to work ok, and Harris says yes. Cooper’s name appears in the text message stream just above this exchange.

As far as the return to the SUV at lunch, Boring said to the jury, looking at enhanced photos you tell me what he was doing.

Harris left his son in the car, he came back to that car, Boring said. When you’re inside the frame, you have a clear view inside. As you’re approaching, you have a clear view. Then he avoids putting his head in.

Why would he come up to a car, open up the driver’s side door, open it and instead of getting in, stop with your head up and throw lightbulbs? Who would throw lightbulbs? Someone who doesn’t want to get in the car because he knows what’s there, Boring said.

We learned from Home Depot employees that Harris brought Cooper to daycare about 80 percent of the time. When Harris would bring Cooper in after having Chick-fil-A, Cooper was always awake, Boring said.

What did we learn from the witnesses in the case?

The car seat was inches from the defendant. It would have been impossible to not see that child,” Boring said.

Harris would have been a position to see Cooper’s head three times, he said.

The Home Depot web developer walked away from his son at the scene – leaving strangers to try to revive Cooper.

“What would any reasonable person have done? They would have called 911,” Boring said.

He sat in the back of the patrol car at the scene complaining that it was too hot inside.

Regarding the mistaken measurements initially used by the 3-D scan of the vehicle, those mistakes were corrected before the jury saw the scan.

“What you were presented by the state was absolutely accurate,” Boring said.

How could he have been Googling vacations June 9 if he intended to kill his kid? Boring asked. Common sense says he probably vacillated back and forth until he had the opportunity to kill Cooper, Boring said.

What does he stand to gain?

He doesn’t have to worry about taking care of his child anymore, Boring said.

There’s no doubt he wanted to go on vacation, he talked big, he thought big absolutely,”

On June 9, 2014, when Googling about possible vacations, he asked if kids can go on cruises for free. He didn’t search for how awesome cruises are for kids. He was concerned about money, and Harris had complained in the past about how expensive kids are, Boring said.

Going back to criminal negligence, he knew the dangers of leaving a child in a hot car more than anybody, Boring said.

“This was no negligence. This was intentional,” he said.

Even if Harris loved Cooper, “humans are capable of awful awful things, -- especially selfish humans who are obsessed,” Boring said.

Yes many people said he was a good dad and loved his son, but they didn't know about his double life.

If Harris had backed into the parking space next to the woodline, Cooper wouldn’t have gotten any sun.

Yes, people walked by the car and didn’t notice anything, but “This wasn’t their child. This wasn’t their car,” Boring said. They didn’t stop by the car at lunchtime to throw something inside like Harris did.

About the smell.

Let’s talk about inside the car and outside the car, he said. Who are the three people who went inside the car that night? They were Stoddard and two other law enforcement officers.

All three of these officers are going to risk their careers and make it up? Boring said. The crime scene investigator who didn’t report a smell, also never entered the car, he said.

Stoddard also didn’t lie at the preliminary hearing about when Harris threw the lightbulbs into his car at lunchtime, Boring said. The detective never said that Harris put his head into the car or that Harris definitely saw Cooper.

That is word tricks on the part of the defense, Boring said. Ask them, are they lying to you?

Lead detective Phil Stoddard did not lie, Boring said. “He got testy on the stand, a little bent out of shape.”

He’s been living this case, pouring blood sweat and tears into interviewing everyone he could, Boring said. And he has to argue over the meaning of what “research” is – whether it’s clicking on a link or typing a phrase into Google.

Stoddard did not lie on the stand. Harris did go to a website about living child-free lives, Boring said.

Regarding wanted to live a so-called child-free life:

After Harris responded “grossness” to a link to a child-free subreddit sent to him by his friend, he looked at other articles on the site, Boring said.

He never thought the police were going to get onto his act,” Boring said. He thought all along that he was going to be an advocate for preventing leaving kids in hot cars.

What was most important to him in his life? Boring asked. Do you really think he was going to delete all of the lewd text messages and photos he saved on his phone?

“Absolutely not because that meant more to him than that child,” he said.

Harris sat in the car for 30 seconds, bent over to pick up his briefcase on the front passenger side floor and grabbed his cup from Chick-fil-A.

There is no way he missed that child, Boring said.

He is now addressing specific arguments the defense made in its closing.

Leanna Harris was never going to accept that her husband was capable of this. She stayed with this man for years.

“She finds out her son is dead and the first thing she asks about is her husband,” Boring said. “She kind of got treated like a doormat for years.”

Boring is going over the timeline of the day of Cooper’s death.

On June 18, 2014, between midnight and 1 a.m., Harris was sexting, wrote one work email and Googled how much a child passport costs.

Cooper wakes up at 5:30 a.m. Harris starts sexting again shortly thereafter.

At 8:59 a.m., Harris takes Cooper into Chick-fil-A. Around 9:15 a.m., while he and Cooper are still at Chick-fil-A, he writes to a woman that “I love my son and all but we both need escapes.”

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Boring pointed out again that the defense said in its opening statement that Harris was not sexting before he got to Home Depot the day of Cooper’s death. That wasn’t true.

“They got it wrong and they can’t admit it because he is guilty. To admit that would be to admit guilt.”

At the end, the defense pointed out that Harris responded to random Whisper posts, Boring said. But he said 10 minutes before leaving Cooper in the car that he needed a break from his son.

Strangers and police officers on the scene cared more about Cooper than Harris did, Boring said.

“The only justice in this case, in the courtroom today is a verdict of guilty on all counts,” he said.

Court is back in session. Lead prosecutor Chuck Boring will now give his rebuttal remarks to the defense's closing argument.

“Justice in this case is nothing more than justice for that little boy,” Boring said.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

The defense attorney shows the video that was shown during trial of Harris playing the guitar with Cooper. Harris is sitting on a bed with Cooper, strumming an acoustic guitar, and Cooper is bouncing up and down and smiling, clearly enjoying the music.

In the courtroom, Harris is weeping only.

Now two hours into this closing argument, Kilgore concludes with the video and tells the jury: "We trust you."

The court breaks until 1:30 p.m.

Now Kilgore puts up slides that go into exhaustive detail on the meaning of "reasonable doubt."

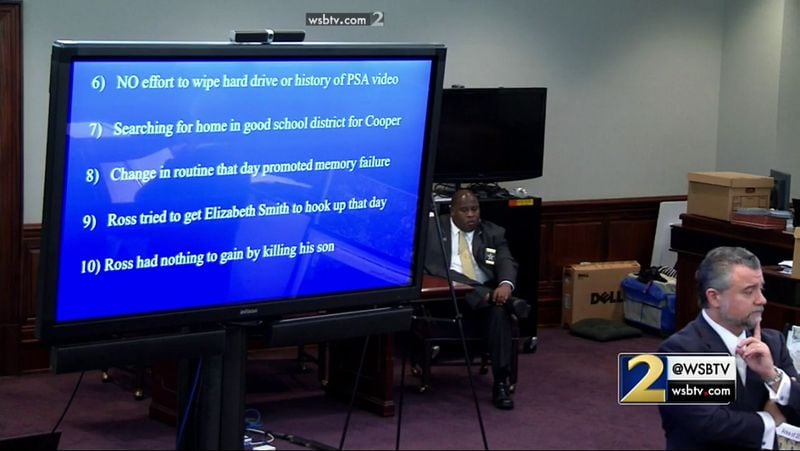

And he puts up 10 points of evidence that would provoke reasonable doubt Harris deliberately killed his son.

"And you only need one," he says.

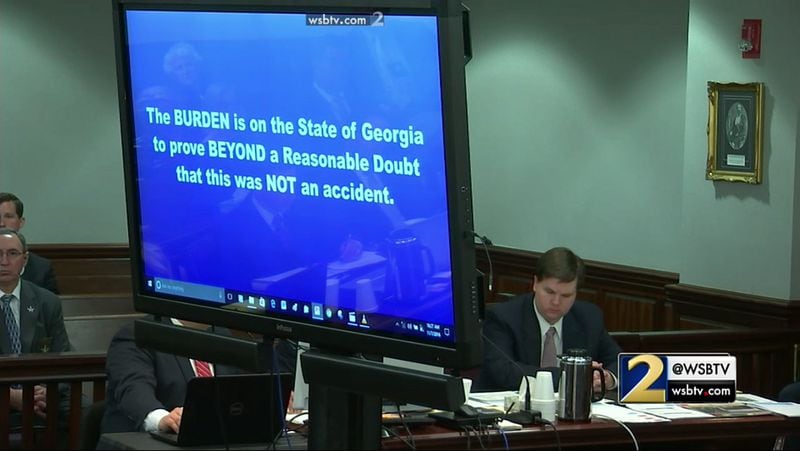

If the jury finds reasonable doubt, "It is your duty under the law to write two words: Not guilty."

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Kilgore tells the jury that it must resist the impulse to find Harris guilty simply because he is unlikable as a person. But he admits the attractiveness of that outcome. "Nobody would question you," he said.

But he said that's not justice.

"Justice is holding the state to their burden," he says. "What could possibly be more just than saying to the state of Georgia, "We have followed the law. We've held you to your burden. And you haven't proven it. You haven't disproven that this was an accident. What could possibly be a more beautiful example of justice than doing the hard thing, then writing those two words. The state hasn't proven it, and he's not guilty."

Kilgore says the state's strategy, by putting up all the evidence and testimony about Harris's sordid secret life, is designed to cover him with so much slime that the jury will find him guilty.

"None of that, none of that has got anything to do at all with Ross forgetting Cooper on June the 18th. It hasn't got ANYthing to do with it. Nothing. How does Ross getting fellatio in a car in Tuscaloosa a year and a half before Cooper died, how does that have anything to do with Cooper's death? At all?

"We all see what this is all about. The state wants to bury him in this filth and doubt -- of his own making -- so that you'll believe he is so immoral, so reprehensible, that he could do this. ... The problem is, the testimony that Ross loved Cooper is unrebutted."

The lead defense attorney says the state's complaints about the way Harris and his then-wife reacted to Cooper's death is nonsensical.

"None of us knows how we would react to that particular trauma," he says. "Nobody knows."

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Kilgore, who is now 90 minutes into his closing argument, turns to the the Whisper image the state emphasized throughout the investigation and during opening statements: "I hate being married with kids. The novelty has worn off, and I have nothing to show for it."

"That was their centerpiece," Kilgore said. "And the centerpiece isn't even something that Ross wrote. ... What does Ross do? He engages. He tries to connect. ..."

Prosecutor Chuck Boring opened his argumeent with a quote from Harris that he made in response: "I love my son and all, but we both need escapes."

"What he doesn't say is what the state is trying to suggest that he says: 'I love my son and all, but I'm about to murder him in the next 15 minutes.' Of course he doesn't say that."

Kilgore turns to the state's early contention that Harris had searched for "child free" websites. Defense experts testified that he never ran any such searches.

"Det. Stoddard couldn't tell us when he found out that information, when he knew this grand evidence of motive was bogus. But we know this. He never wrote a report about it. I think it's fair for you to ask yourself, were the police just hoping Kilgore wouldn't find out about it? But he did.

"You've been misled. You have been misled. Throughout this trial.

"Your responsiblity is to hold the state accountable. You hold them to their burden. And if you see or recognize an effort to mislead you in any way, you are to remember that when determining credibility in that jury room."

Kilgore points out that the state blew its analysis of Harris's work on a website for Griffin Psychology. Police and experts suggested that Harris's development of the site indicated something nefarious on Harris's part. Kilgore calls this whole line of evidence a "fraud," saying that Harris was engaged in a perfectly legitimate business pursuit.

The prosecution expert testified that Harris frequently "cleared his cache," indicating that he was trying to hide something.

"He found that so suspicious that he threw around words like 'crafty' and 'Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,'" Kilgore said. He points out that web developers frequently "clear cache" as a routine part of their work.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

In his methodical examination of the prosecution case, Maddox turns now to the incendiary claim by detectives that they smelled the "stench of death" at the scene. He notes that no one noted that stench in reports until many months later. And then he cites a medical examiner's testimony:

"I don't believe you have decomposition smell per se," Kilgore says. "I don't believe the odor would be the same as the odor of a dead body. ... Maybe a stale odor of breathing, urine, flatulence."

Then he ridicules what he describes as Stoddard's backpedaling on the stand. "Well, when I said decomposition, I didn't mean that like in a medical sense. I didn't really mean decomposition when I said decomposition. He finally agreed that it's possible he didn't smell a thing. Hardly the resounding smell of death we hard about in opening statements.

"Those detectives most invested in the case -- Det. Stoddard, his boss -- they reported smelling what they wanted to smell. In spite of what everybody else couldn't smell, they reported what they wanted to smell. Why? Becuase it supported their theory."

Kilgore then talks about what he calls the state's ludicrous assertion that Harris's then-wife, Leanna, was somehow complicit.

"We also heard from Det. Stoddard during the trial that Ross's former wife, Leanna, has been a suspect during the entirety of this investigation. Not actively, right now. They just didn't have enough for probable cause. Well, if the theory is that Ross murdered his treasure to free himself of this marriage to Leanna, how in the world could she be involved in the conspiracy to do that? How is that possible?

Leanna's going to assist Ross in murdering their little boy so he can free himself of a marriage to her. It sounds absolutely ludicrous.

"But if Leanna has been a suspect for two years, that's what you would have to buy ... that is the cockamamie story that you have to buy. It's absolutely ridicultous. And yet wtih no evidence whatsoever, she's been a suspect. Did you kind of get the feling that the detectie was just itching to tell us that she was still a suspect? Did any of you get that feeling?

Like Ross, she didn't cry enough in front of them. She didn't grieve enough in front of them on the worst day of her life."

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

He reminds the jury of its early morning visit to the courthouse parking lot to view Harris's 2010 Hyundai Tucson, the vehicle in which Cooper died and, according to the prosecution, "the murder weapon."

He tells the jurors that they knew to look for the car seat when they went out to see the car.

"It's easy to see what you're looking for. In fact, it's impossible to miss what you're looking for. ... How do we know that Ross didn't see Cooper. Because he didn't freak out right there in the parking lot and pull him out of the car like he did at Akers Mill (when, according to Harris, he discovered Cooper was still in the vehicle).

"It's real clear that he didn't turn his head. It's real clear that he can't see something that's behind him."

Now the defense attorney returns to the testimony and investigative work of Cobb police Det. Phil Stoddard. He replays a video of Harris putting light bulbs into his car after lunch that day. Stoddard testified that Harris was "in there" within the frame of the vehicle and that Harris could easily have seen his son in the back.

"As you can see for yourself, he's not 'in there.' He doesn't have a clear view. Ross's head never goes below that roof line. So I think it's a very fair question to ask you this, When the detectives in this case take the stand and they swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, is it? Or are they going to tell the truth (that supports) their theory?"

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Kilgore has been speaking now for nearly an hour. He has warned the jury that since the prosecution gets to speak to them twice during closing arguments -- and he only gets to speak once -- he is likely to take a long time.

He hammers again at the state's 3D laser scan of the SUV that showed the position of the car seat and of Cooper in the seat. "That scan was made for the purpose of showing you -- you -- what Ross might be able to see." But he points to details that were incorrect, such as the fact that the doll used to depict Cooper in the seat was wearing bright white socks on his feet -- socks that showed up very clearly in the state's image. In fact, Kilgore says, Cooper was wearing blue shoes.

The position of Cooper's car seat -- and its proximity to the defendant in the driver's seat -- was a key part of the state's case. Kilgore points out that the car seat, when Cobb police replaced it in the car after processing it as evidence, was placed in a different position. "It's very significant. All they had to do was look at those photos to see, they're not the same. The angle was wrong. ... The bottom line is, they were prepared to come in here to this trial and show you a scan which was wrong. Which was absolutely wrong. That's what they were prepared to do. And if we hadn't pointed it out, that's exactly what would have happened."

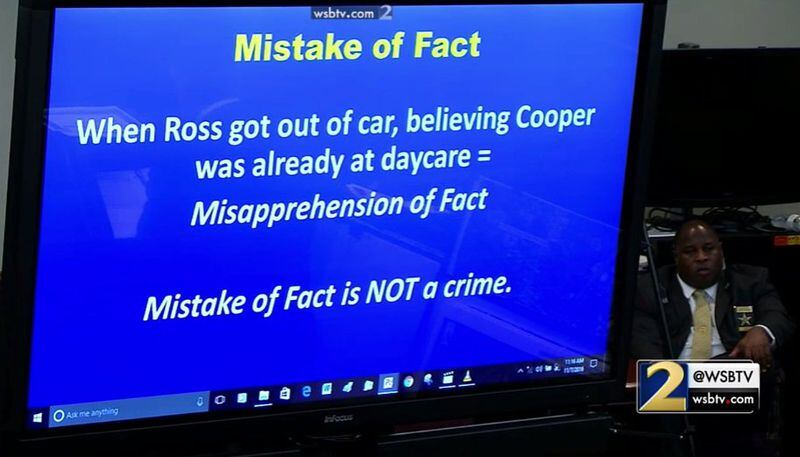

Kilgore: "Ross had taken to Cooper to daycare so many times, he had lots of memories of that. Remember what he told Officer Piper: I could've sworn I dropped him off."

This was an example of what the defense's memory expert called "false memory."

A "misapprehension of fact" is not grounds for a criminal charge, Kilgore says. "The law calls that a mistake, not a crime."

Now Kilgore turns to the defendant's daily routine -- when he took his son to breakfast at Chick-fil-A, when he went to the restaurant by himself and when he took Cooper to daycare at Little Apron Academy.

He points out that no Chick-fil-A employee said he or she had seen Cooper at the restaurant with his father between March 14 and June 18. "It was the exception. It wasn't the normal route. Taking Cooper for breakfast was clearly the exception. But he took him on June the 18th."

He cites testimony by a memory expert who said it was possible for Harris to forget Cooper was in the car "in seconds."

Kilgore talks about why Harris left all the evidence of his sordid life on his phone.

"This is the real kicker. He doesn't even delete the Kik app on his phone. He doesn't delete the Whisper app? That';s where all of this filthy information comes from, and he doesn't even both to delete the apps. And then, that very day on the 18th, what does he do? He spends the day putting more filth on his phone, on the Kik app, on the Whisper app. ... All he's gotta do is delete the app. I think it's a good question to ask yourself, Why doesn't he?

"Isn't the most likely answer because there was no murder underway? He's got no reason to think anybody's going to be looking at his phone. No reason at all."

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

The defense attorney argues that the chief premise of the prosecution -- that Harris wanted to jettison his son and his wife so he could have sex with multiple women and sext to his heart's content -- has a central flaw. "He was already doing what he wanted to do,"Kilgore says. " ... What in the world does he gain (by killing his son)? What has he accomplished? What is his reward? He's already doing whatever he wants to do."

Kilgore tells the jury that Harris's planning the cruise is strong evidence that the defendant had no intention of killing his child.

"There is no way around it. To find Ross guilty of murder, you bascially ahve to just ignore it. Like it was never even brought out. Why? Because a person planning to do what they say Ross did -- that kind of person is not planning to take his child on a cruise."

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Kilgore then talks about how Harris planned a family cruise -- nine people: Harris, his wife Leanna, Cooper, and Harris's brother Michael Baygents, his wife and their four kids. "He's planning a family cruise with Cooper, and he's clueless that Cooper's out in the car, because he forgot. The police knew about these emails with (travel agent Heather Coyle), and they never bothered to call the woman. How do you explain that? District attorney didn't even call her until September, just a few weeks ago."

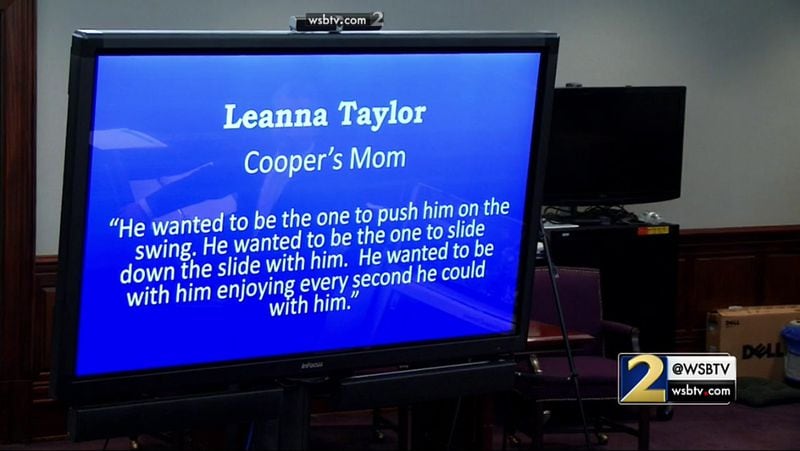

He moves on to deal with the prosecution assertion that Harris was living a double life. "There appeared to be a constant in both lives, and that was that he loved his little boy. ... He. Loved. That. Little. Boy."

The state said that Harris wanted to escape from Cooper so badly that he was "willing to destroy the treasure of his life. To do that, there's got to be some serious hatred ... toward that little boy. The kind that would permeate your life and come out of your pores. But not one witness has indicated anything like that.

"What evidence has the state shown you that Ross hated that little boy? Who are the witnesses who rebutted all the testimony that Ross loved his little boy more than anything?"

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

"Everybody that knew him said he loved that little boy more than anything," Kilgore says.

He then cites testimony from women with whom Harris was sexting: even they, Kilgore says, believed that Harris loved his son.

"Every single witness we heard from in the trial who had any knowledge of the relationship between Ross and Cooper -- everyone testified that he was a loving and proud father. .... Do you think his ex-wife and her best friend would come in here and testified if they had any doubt. ...

"Ross ruined that women's life. He humiliated her in front of the world. He took her son away. You really think she's going to come in here, and her best friend is going to come in here, and say anything about how much Ross loved his little boy, if they didn't know that this was an accident? Think about that."

Kilgore: "Ross forgot. He didn't choose to forget. He just forgot. And it doesn't matter what he's thinking about. Sports. ... Work. Sex. Whatever. Why? Because you don't anticipate that you're going to forget. That's not how it works. And when he got out of the car with Cooper at the Treehouse (Home Depot's office building, where Harris worked in IT), he'd forgotten him. He'd already forgotten him. ... Without that knowledge ... if he didn't have absolute knowledge that Cooper was there, it can't be criminal negligence. He had to have that knowledge. But he forgot."

Defense attorney Kilgore continues: "He failed. He left him in that car. ... He is responsible. Only him. Nobody else. And he has acknowledged that from Day One. He is responsible. But responsible is not the same thing as criminal. It is not. The state has not disproven that this was an accident. It is their burden to do so. And there is a reason they can't disprove beyond a reasonable doubt that this was an accident, and that's because it was."

He points out that Harris faces three counts of murder.

"Murder is murder is murder. Whether he's convicted of count one, two or three, they're all the same in Georgia. You need to know that when you consider his fate. Each count is just a different theory of murder. And the state's entitled to do that. ... But we spent 21 days of them charging down one track or another.

This entire trial has been about count one: malice. He meant to do it, he intended to do it. That's been their case. That has been what they've tried to sell you throughout this entire trial.

I think it's become very clear that Ross treasured Cooper and had no reason -- no reason -- no reason to kill him. Count 2, felony murder would be that Ross meant to cause Cooper excessive physical pain... and Cooper died as a result of that. There is absolutely no evidence of that.

Count 3, that Ross acted with criminal negligence in committing cruelty to children and Cooper died as a result of that. ... You really need to understand, this is a legal phrase with a legal definition. It is not the same as simple negligence. It's not the same as being careless.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Kilgore is sharply critical of the police testimony that Harris did not show sufficient emotion, or that the emotion he did show was faked.

"If he's putting on some kind of show for somebody, why's he doing it alone? Why's he doing it in the room after they closed the door?"

"Mr. Boring told you in opening and today that the only thing to consider here is malice. ... You've heard teh interview. You've followed along on the transcripts. And what Ross said to the detectives over and over again was this was an accident. ... If it's an accident, it's not a crime."

Maddox Kilgore begins his closing argument by immediately going after the lead investigator for Cobb County police, Det. Phil Stoddard.

"He'd already decided the case. He'd already decided a crime had occurred. He'd already passed judgment. He'd already completely precluded the possibility that this was eactly what it was: an accident. It was Det. Stoddard's boss ... he's wrong. He's wrong for a lot of reasons. The first thing I want to talk about is legally why he's wrong. In this state, accident is a defense."

Court is still on break. Georgia criminal procedure provides that the prosecution begins closing arguments and also concludes them, with the defense argument sandwiched in between. (If the defense offers no evidence, the defense opens and closes the arguments. In the Harris case, the defense did put on a case, so the prosecution takes the lead.)

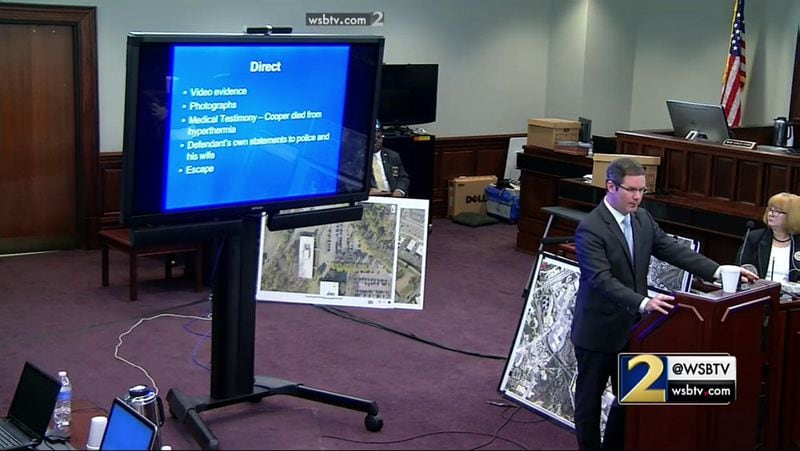

Prosecutor Chuck Boring led off with a powerful statement for more than an hour. before concluding at 10:08.

Boring showed the jury a photo of how the car seat looked the day of Cooper’s death. It’s right next to where Harris’ head would have been.

“It all comes back to this. That’s how that cars eat looked on June 18, the defendant is guilty of all counts,” Boring said.

The court is now taking a break.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

It took Harris 30 seconds to decide not to take Cooper to daycare, Boring said.

“Malice is shown in his two lives in this case and his desire to escape from one of them to leave the other,” Boring said.

It all comes down to a matter of inches – the distance from where Cooper’s head was to Harris, he said. The defendant is guilty of malice murder and all of the counts, he said

“This killer’s heart abandoned this child long before he died,” Boring said. “(Harris) sat there malignantly while that child cooked in that car.”

There is no requirement to prove premeditation.

Malice can be formed in an instant. There is no premeditation is required. Although the evidence screams that he had been thinking about this for some time,” Boring said.

The final count Harris faces is felony murder with malice.

“This isn’t a case about an adult hating a child,” Boring said. “It’s just that he loves himself and his other obsession more than that little boy.”

Malice in this case is killing without justification, excuse or mitigation.

“Killing a young children, there is no excuse for it,” Boring said. The fact that he was a good dad on other occasions does not excuse what he did, the prosecutor said.

No doubt Harris is guilty of criminal negligence, Boring said.

Harris also faces felony murder counts involving malice.

Malice is not ill will or hatred, Boring said.

For this count, it means intent to cause particular harm – in this case pain – or the wanton or willful doing of an act with an awareness that such harm may happen, Boring said.

Criminal negligence is wanton, willful or reckless disregard of others that may reasonably expected to be injured by that act.

Harris knew all about the danger of leaving a child in a hot car. Harris and his wife talked about it.

The defendant knew he could prevent that from happening and he didn’t, Boring said.

This defendant’s obsession was more than criminal negligence. “It was an intentional murder,” he said.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Felony murder does not require the intent to kill or any type of malice. What we have is criminal negligence, Boring said.

There was cruel or excessive physical pain. “There is no doubt about that how this child suffered,” he said.

Based upon those acts, the child died, that’s it cut and dried, Boring said.

The defense in their opening statement said they wanted you to pay attention to something crucial in this case – a linchpin of their case. He told you the defendant was not sexting that day until after he dropped Cooper off.

"That’s what they were hanging their hat on in their opening,” Boring said. “We know that’s not the truth. That’s not the evidence. That’s not what happened.”

He also faces charges of sending explicit and detailed verbal descriptions of sexual excitement and sexual conduct. Harris was coaching a 16-year-old on how to perform oral sex, Boring said. Harris was 33 at the time.

“It is harmful, who knows the psychological issues down the road,” Boring said.

The same crime is also charged in a different manner. He sent a photo of his penis to the under-aged girls too.

Boring is talking about the charges Harris faces.

He faces sexual exploitation of a minor – somebody less than 18 years old. He took a substantial step to persuade, entice a minor to send a nude photo. That can be committed by not only getting someone to send a photo or being in possession of it.

“What we have is him trying to get that,” Boring said. The girl was a junior in high school.

“This was an attempt that was ongoing … repeatedly over and over and over again,” at least six requests from the defendant for the child to send him a picture of her genital area, Boring said.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Dr. Brewer gave expert testimony about memory failure. If this was intentional, his testimony was meaningless, Boring said. In fact, some of his testimony ended up supported the state’s case. Brewer was unaware of a lot of Harris’ actions leading up to Cooper’s death, Boring pointed out.

Words, conduct, demeanor and motive are all things that are to be considered, Boring said.

Given Harris’ double life, “I think actions speak louder than words,” he said.

The defense will say that everybody reacts differently in times of trauma. “People react in different ways but not in the way (Harris) did,” he said.

Circumstantial evidence includes the defendant’s route from work to the movie theater wasn’t the right route. The smell in the car is circumstantial evidence. The lies in his timeline about lunch – not initially telling the police that he stopped at his car after lunch. His demeanor with people saying his reactions were inconsistent, Boring said.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Direct evidence and circumstantial evidence are equal, Boring said. They are just two different ways of proving a case.

Circumstantial evidence is proof by inference.

It’s like when you pump gas, said Boring, who drives a Nissan Versa. You don’t actually see the gas go into the tank but when you’re done, the tank is full. You can then infer that the gas went into the tank.

“Now that you’ve heard all the evidence there is no doubt that Cooper was burned to death in that car” Boring said.

In its opening statement, the defense said that Harris was responsible for Cooper’s death.

“Responsibility is guilty in this case,” and there’s no doubt that Harris is guilty of all of the charges, he said.

Harris was an expert in hot car deaths by the time he killed Cooper, Boring said. In the hours after Cooper’s death, he was already talking about wanting to be an advocate – drawing more attention to himself that way, he said.

Harris thought he was going to get away with it, the prosecutor said. “He thought he was smarter than anybody else and he didn’t think anyone was going to call his bluff,” Boring said.

The defendant’s own brother said that sometimes the victim is someone the defendant actually loves.

“Oftentimes it is the last person you would expect to do evil to a child,” Boring said.

No witnesses called by the defense or prosecution who had been in Harris’ car ever said you couldn’t see Cooper from the front seat, Boring said. If Cooper was visible even without all of the other things that would have drawn Harris’ attention to his son, the defendant is guilty of all counts, Boring said.

While he is on the way to Chick-fil-A and sitting there with his son, he was responding to a Whisper message from someone saying they had nothing to show for being married.

He told this other person he couldn’t lead his other life the way he wanted,” Boring said.

It’s been days and days of testimony, he said. “It’s like groundhog day.” You all know you’re going to hear filthy stuff and gruesome facts every day, Boring said.

But what it all comes down to in this case can be summed up by the defendants own witnesses.

This case doesn’t fit the typical case of a failure of memory systems, Boring said. That was clear from the defense’s own expert witness, he pointed out.

He was in the car for 30 seconds with Cooper before leaving. He had to lean over to get a briefcase on the passenger side door, and he also got his Chick-fil-A cup – that he had just gotten while having breakfast with Cooper.

In one message with a woman, he said that his conscience never kicked in, Boring said.

He professed love for many of these young girls, he said. The woman who he was most attached to was slipping through his fingers. She was gradually cutting him off. The day before Cooper’s death, he messaged her and she didn’t respond. The girl was 18 at the time.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

In the weeks after a family vacation, at a time his wife was asking him to come home to spend some time with her and Cooper, he lied to her about what he was doing and he went to a seedy Marietta hotel and had sex for money with a prostitute, Boring said.

His behavior was escalating in the weeks leading up to Cooper’s death, he said. Harris was sexting with a 15-year-old.

Harris led a double life. “That is the other Justin Ross Harris,” Boring said forcefully.

That car seat was clearly visible to anyone inside that car, Boring said.

Five days before, Harris watched a video about how hot it gets in a car, Boring said. Even with a breeze and the windows cracked, you can kill a living being in no time at all, he said.

That’s a situation Harris, in his own words, contemplated for his son, Boring said. Harris knew the effectiveness of a hot car in killing a child.

“He closed the door on (Cooper's) little life because of his selfishness because of what was more important to him -- his obsession and his other life,” Boring said.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

Boring is now beginning his opening statement.

“I love my son and all but we both need escapes,” Boring said, repeating the line again to the jury. Harris sent that text message to a woman the morning of Cooper's death.

Those words were uttered 10 minutes before this defendant with a selfish and malignant heart did exactly that, Boring said.

He drove Cooper into that parking lot and “left him there to die,” Boring said. On that morning, he did exactly what he said he was going to do, he said.

Harris sat in the car for 30 seconds with his son inches from him “before closing the door on that little boy’s life,” Boring said.

The jury has entered the courtroom.

Lead prosecutor Chuck Boring is actually going to give an opening statement. He will be followed by the defense's closing argument. And then the prosecution will have the last word.

Credit: WSB-TV

Credit: WSB-TV

About the Author