One of the most compelling authors at the recent AJC Decatur Book Festival was Rutgers University historian Rachel Devlin, who wrote about the African-Americans girls at the forefront of America's desegregation battle.

Devlin drew the title of her book, "A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women Who Desegregated America's Schools," from prominent NAACP lawyer Charles Houston's closing argument in the 1941 Bluford v. Canada desegregation case.

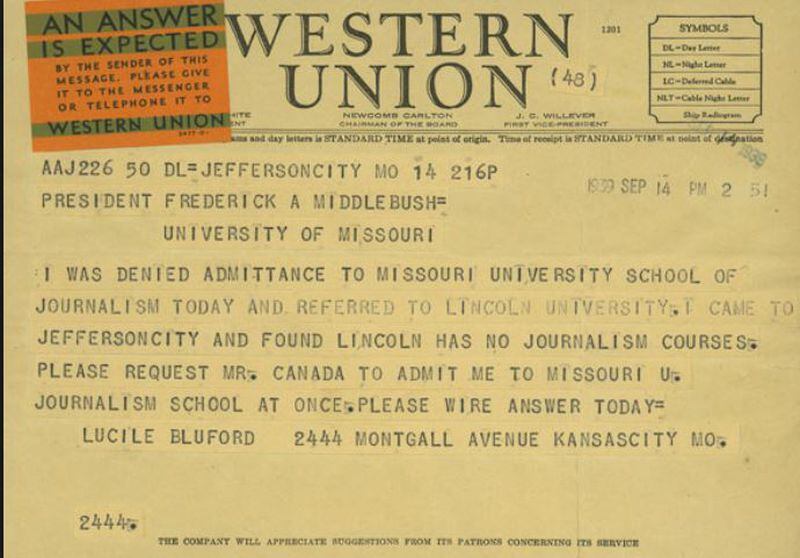

Lucile Bluford was a young journalist who challenged Missouri's Jim Crow laws by repeatedly applying to the University of Missouri graduate journalism program; S.W. Canada was the university registrar.

In decrying the laws that locked Bluford out of the University of Missouri, Houston declared, "A girl stands at the door and a generation waits outside."

In this piece, former AJC education reporter Diane Loupe talks about the Bluford case. A freelance writer and substitute teacher, Loupe holds a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri. She learned at the book festival that a piece she wrote about Bluford was a source for Devlin’s book. When Loupe mentioned that connection to me, I asked her to write a piece about Bluford.

By Diane Loupe

A white man and a black woman are running head-to-head to become governor of Georgia, but a few generations ago, the two would not have been legally allowed to attend the same school.

The fact that children of all races mingle today in public schools is largely due to the brave young African-American women at the forefront of the movement to desegregate America’s public schools. “A Girl Stands at the Door” by Rutgers historian Rachel Devlin chronicles the experiences of the many of those young women.

Some are familiar to us. Think Linda Brown in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision or Ruby Bridges trying to enter an all-white New Orleans school. However, many of the brave young women were unheralded, and Devlin gives an extraordinary account of their ordeals.

Devlin spoke recently to a large audience at the AJC Decatur Book Festival and it was there I learned, to my astonishment, a paper I wrote for a history class at the University of Missouri, later published by Journalism History, was a source for her book. In the article, I wrote about the efforts of Lucile Harris Bluford to attend the then-all white graduate school of journalism at the University of Missouri.

Ms. Bluford was everything a good journalist should be – persistent, ambitious and hardworking. In 1939, when she applied to the Missouri j-school, the nation’s oldest and most respected school of journalism, she was the 28-year-old managing editor of the Kansas City Call, the city’s preeminent black newspaper.

Her desire for an advanced degree reflected a family who valued education. Her father had degrees from Howard and Cornell; her mother was an Oberlin College graduate. Her brother had a degree from the University of Kansas, where Ms. Bluford earned a degree in journalism, paid for by the state of Missouri. At the time, Missouri underwrote the education of black residents in other states if the majors they wanted weren't taught at Lincoln University, the black college in Missouri.

It was because of her Kansas degree that Missouri officials at first admitted her to the graduate school, unaware of her race. But when Ms. Bluford stepped on campus on Jan. 30, 1939, and stood in line to enroll, a woman from the registrar’s office asked her to step out of line.

She was told she could not attend the all-white campus. That didn’t stop her from applying 11 times, all while continuing to work as a journalist and covering her case in the pages of her newspaper. In 1942, Missouri shut down the graduate school rather than admit the soft-spoken Ms. Bluford.

As a graduate student reading historical news accounts of Ms. Bluford’s case, I was fascinated by the differing perspectives of black and white journalists. Black newspapers wrote prominently that white female students from nearby Stephens College had filled the courtroom and applauded Ms. Bluford. I could feel the disdain of a white reporter from the Columbia Daily Tribune who wrote dismissively of the 100 or more “girl students” who were “wearing anklets despite the sleety weather.”

Ms. Bluford never did get to attend Missouri, but she had an impact on the school. The university gave her an honor medal in 1984 and later named a dormitory in her honor. By all extant accounts, the adult Ms. Bluford was treated cordially by white officials, even as they denied her admission.

Not so for the black girls and teens who were the first of their race to attend white schools. White teachers openly used the N-word to refer to these young women. Some were spit upon, taunted and called stupid. They received threatening letters.

When 14-year-old Marguerite Daisy Carr attempted to integrate a Washington, D.C., school, her father, who worked at the Pentagon, was fired, along with everyone in his crew. According to Devlin’s book, President Truman quietly got them all reinstated.

In 1958, Georgia was among the southern states with laws ready to close schools if desegregation was imminent. In 1964, 10 years after the Brown decision, fewer than 2 percent of black schoolchildren in the south attended desegregated schools, according to Devlin’s research.

Her book recalls the Monday morning that McDonogh Elementary in New Orleans was to admit three black girls. White protestors chanted racial slurs and told the little girls to go home. When the 6-year-olds saw the crowds around their school, they thought it was Mardi Gras.

“I was scared,” Gail Etienne recalls in Devlin’s book. “Crowds of people saying all kinds of things. If they could get to me, I thought they was going to kill me.”

The girls were forbidden to play outside of McDonogh Elementary, so they played under the stairwell. They received so much hate mail that the NAACP screened the letters first. A hearse drove in front of one girl’s home.

The legacy of black women committed to education continues. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, black women in 2009 earned 68 percent of the associate's degrees, 66 percent of bachelor's, 71 percent of master's, and 65 percent of doctorates awarded to African-American students.

On social media, I frequently see white people complaining that one news medium or another is “playing the race card” whenever they write about racial problems. I doubt they realize the sacrifice black parents made to ensure what any parent would want: the best education for their children. I wonder how they can think centuries of discrimination can be wiped out in a generation.

The stories of these brave young women are echoed in Maya Angelou's poem "Still I Rise."

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

About the Author