The Dancer

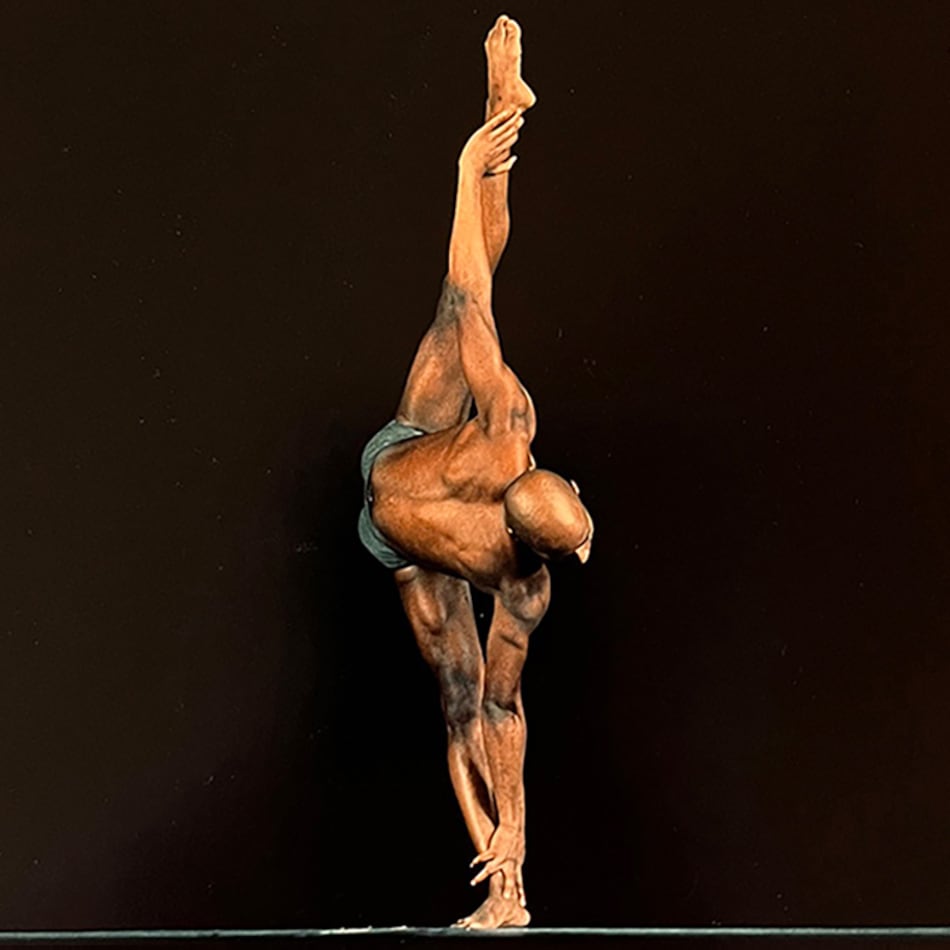

Photographer Joanne Savio, choreographer Duane Cyrus

A beautiful and tragic life

The drugstore stood dark, its parking lot empty, as the two homeless men approached.

For them, it was a perfect time to pick up a few items. It didn’t matter that the store was closed. They were there to dumpster dive — to rummage through what other people consider garbage to try to find something salvageable.

Trey Nelson’s focus was on that task. Then he heard singing.

He looked up.

The lean older man who had joined him for the late-night foray along Atlanta’s North Druid Hills Road wasn’t just singing. He was dancing. And not just regular-person dancing. This was something else.

His dumpster diving partner was performing ballet pirouettes and graceful leaps in the parking lot.

“It was like I was watching a professional dancer on stage. That’s how good it was,” said Nelson, who remembered years of watching his sisters take lessons at the Atlanta Ballet.

He was amazed when the man — perhaps in his 50s, about 20 years his senior — slowly pulled one leg straight up in the air, resting his heel beside his ear.

“I saw that he was in his own element, in his own world,” Nelson said. “He was happy in that little space.”

In the past, the man had mentioned that he once had been an accomplished dancer. Now, Nelson could see that was no exaggerated tale from another person without a home, scratching out a life in one of Atlanta’s hidden encampments.

“He was one of us that got lost,” Nelson said. “A pretty good majority of us out there have many different talents and abilities and goals — and had something going for us at some point in life. And then something happened.”

Still, Nelson hadn’t heard the full, remarkable truth.

Gerard Alexander’s life once held extraordinary promise.

He was 19 years old when he earned a spot in one of the most iconic music videos ever made, which premiered in a prime-time special on CBS.

Seconds into the choreographed scene of Michael Jackson’s 1987 blockbuster music video “Bad,” the King of Pop and a group of dancers portraying his “tough guy” allies stare down neighborhood bullies. Jackson snaps his fingers and grinds out a couple of hip rotations. Then there’s the first big dance move.

Gerard — wearing sunglasses, a Kangol hat and a black and red tracksuit — slips in front of the most famous entertainer in the world and soars into the air, his legs in a perfect split. As the video rolls, he frequently reappears, sometimes gliding through moves alongside Jackson.

A ballet, modern and jazz dancer, Gerard would go on to perform with professional dance companies, tour in Europe, receive praise in The New York Times and grace the cover of a coffee table book on Black male dancers.

Fellow performers and choreographers called him a phenom. They were awed by his otherworldly flexibility. He had the physique and exacting discipline to make his body do what seemed impossible and the emotional intelligence to move audiences.

Some thought of him as a Black Baryshnikov, comparing him to one of the most famous male ballet dancers of the last century.

But while Gerard eagerly displayed his artistry and grace, he camouflaged deep wounds.

Gerard kept secrets.

Credit: Tyson A. Horne

Chapter I

Some kids are always in motion. They are the living embodiment of Isaac Newton’s first law: An object’s speed and direction are eternal, unless acted upon by an external force. Like gravity. Friction. Life.

As an elementary school kid in the 1970s, Gerard tried out new dance moves in the hallways outside the 11th-floor apartment he shared with his grandmother and a younger half-brother. He’d jump from stairways and land on the floor in a split. He sliced his leg open once when he hit shards of glass while doing that.

I couldn’t keep him still, his doting grandmother would tell people. He was always dancing.

When girls in his apartment building began taking dance lessons, Gerard watched them practice and mimicked their moves. He was easy to hang out with. Girls saw in him a boy who was kind, empathetic and effeminate. “He was more girly than I could ever be,” one of them remembered decades later.

The apartment tower overlooked the Passaic River in Paterson, New Jersey, a bus ride of an hour or more from New York’s Broadway theater district. Paterson could be dicey. Crime loomed near the tower. Empty drug vials sometimes littered the ground.

Gerard’s grandmother, Ruth Alexander, tried to look out for him.

She had lost use of much of the right side of her body, which some thought was due to polio. Still, five days a week she’d travel to nearby towns to work as a housekeeper.

Gerard — that’s the name he went by, though legally, he was Jarrod — adored his grandmother.

Childhood friends don’t remember Gerard talking much about his father. His mother, Doris Alexander, left the kids behind when she moved to California to be with a man and pursue dreams. When she was around, there could be turmoil. She grappled with serious mental health issues and drug addiction, Gerard confided to his closest friends.

Another thing he told only a few people over the years: As a child, he was repeatedly sexually molested. At times, he would play it off as though it wasn’t a big deal. He would do that — he talked about the sunshine in his life, not the inner tempests.

Credit: Joanne Savio and Duane Cyrus

Dancing became the sunshine or, maybe, the salvation. When some of his friends took free dance classes provided by a nonprofit, Gerard did, too. At around 10 years old, he tagged along as some visited a ballet school in Newark in pursuit of more free classes. An instructor there had trained successful professional dancers and had been one himself.

That day was cold. Gerard was in one of those puffy bubble coats and wearing a hood. Alfred Gallman, who mostly taught young Black boys from poor backgrounds, saw a gorgeous face peering out.

Oh, who is this pretty little girl? the instructor later recalled asking himself.

Then he got a closer look and realized that the potential student was a boy. But the real stunner came when he first saw Gerard move.

“If God created somebody who had everything to be a dancer, that’s what he got,” Gallman remembers.

Supple back. Flexible body – rare in a male dancer, especially at the time. Powerful legs. And the feet. Stunning feet. Perfect feet. Big feet that could curve, along with his toes, into a seamless C shape.

“You can’t have bad feet and be a successful dancer,” Gallman said. “He had feet that would rival any ballerina.”

Credit: Tyson A. Horne

Gallman often envisions the hand of God maneuvering the people and circumstances he encounters. Especially when it comes to dance.

At 17, Gallman had so intensely yearned to dance that he stayed behind in New York City when his parents moved to Chicago. As they pulled off in the station wagon, “I fell to my knees and I said, ‘Jesus, let me dance.’ And there is not a day that Jesus has not let me dance.”

With Gerard, he had before him a once-in-a-lifetime student.

The boy could do the most amazing moves right away. What he lacked was training. He needed to learn not only precise movements, but also control, how to keep feet and limbs from flopping, to break his body of any lesser inclinations.

Classes at first were once a week. With a full scholarship from Gallman, they grew to three days a week, hours each time.

The dance inside Gerard wouldn’t stay bottled up. It broke out everywhere. He danced on the subway. He danced in the streets. He danced on the edge of fountains.

By 14, Gerard had mastered motions and control.

“The best jump you ever want to see on a male dancer. He could turn six or eight pirouettes,” Gallman said. The minimum standard for good professional dancers would have been more like three.

He made a six o’clock arabesque penchée look effortless. It involved standing on one leg, with his foot turned out. Then he would lean forward while smoothly lifting his other leg behind him — with toes perfectly pointed — until his foot was high above his head and his legs were in a pure vertical split. He held himself there, without wobbling and without his hands touching the floor.

Still, the training wasn’t done.

In dance, perfection is the expectation, unreasonable as it is.

From the ages of 15 to 18, Gerard’s training switched from focusing on control to developing artistry.

“That is the difference between aerobics and dance,” Gallman said. “Aerobics is just physical movement with no meaning. But dancing is a movement of the spirit and the soul.”

In Gallman, Gerard found a dance father. For his dance son and star pupil, Gallman choreographed a solo piece. The title: “Little Boy Wonder.”

It seemed at every class, his prodigy would come in with a sweet disposition and something funny to share with his friends.

Dancers, even as teens, often are in competition with one another for an instructor’s praise, for a spot on the front line at recitals, for a solo. In class, Gerard would flawlessly perform a move. And when other students tried to do the same and inevitably fell short, he would be the first to reassure them. Then he’d help them learn to do the move better.

“As big as his talent was, he never had the ego that most artists of his level have,” Gallman said.

Years later, some would come to wonder whether Gerard felt worthy of any of it.

His trek from Paterson to Newark by bus offered a chance to enter a different world. He could look regal when he danced, not like a kid facing trauma.

“When he would come to the dance school, I would tell him he was a king,” Gallman said. “Then, when he would go outside, he would be no one. His dancing became his lifeline.”

It was a fragile one.

Being a ballet dancer in a tough neighborhood back then likely led to harassment. So did being gay. Being a Black male and gay carried a tremendous stigma.

Credit: Courtesy of Duane Cyrus; photographer Paul Kolnik

Chapter II

“We were very naïve when we were young,” said Timothy Armour, a Paterson neighbor and fellow dancer. “As we got older, it changed. And Gerard changed.”

The world opened up too soon for the kids from Paterson. Manhattan called to them. Gerard joined friends to sneak into dance clubs in the city. One was Studio 54, famous on the disco scene for its exclusivity, beautiful patrons and rampant drug use.

Gerard was beautiful, too, and could dance with style, enough to gain him admittance to clubs even when he was underage.

He competed for and earned a spot at New York’s High School of Performing Arts, which the 1980 movie “Fame” was based on. A later “Fame” TV series aired while Gerard attended the school.

He landed a scholarship to train at The Ailey School, the founder of which launched one of the nation’s most storied contemporary dance companies.

Credit: Contributed

Then came a big casting call. Michael Jackson was about to make a new music video to pair with the release of an album he hoped would top the monstrous success of “Thriller” a few years earlier. Jackson hired Martin Scorsese to direct the “Bad” video, which ended up being an 18-minute short film.

Hundreds were at the tryout in New York, as dancer Ferdinand De Jesus remembered it. Gerard’s skills made an immediate impression on De Jesus.

“He flew so high in the sky he was like a bird. People said, ‘What the hell is this guy?’”

Gerard won a job many dancers coveted.

Jackson was good to work with, but the dance practices were tough. The pay was nice, though, he told a friend. Better still: Put it on your bio, and it was sure to open doors. Just the original CBS airing garnered millions of viewers. Decades later, people of a certain age can still remember scenes.

After that gig, Gerard quickly landed others. He performed with a touring dance company, and a critic for The New York Times took notice of him. He also scored a featured role in a sold-out musical and dance show that toured Europe. The show’s choreographer, George Faison, was the first Black choreographer to win a Tony award, for his work on “The Wiz.”

Faison was struck by Gerard. “He was very exceptional. Star quality. He could dance for the best.”

It was only years later, Faison said, that he heard rumors about struggles Gerard had endured for much of his life.

Chapter III

Dance is not all tutus and leotards and grace. It’s a brutal culling ground for anyone aspiring to make a full-time living.

Plenty of kids and adults in the United States take dance classes each year. Most aren’t pursuing it as a career. That’s understandable. In the entire nation, there are only an estimated 14,000 full- and part-time jobs for dancers and choreographers.

You need a backup plan, Gerard’s aunt, Betty Alexander, would tell him. You are dancing now, but you always have to have something to fall back on.

I can always teach, he’d answer.

Early on in his training with Gallman, Gerard would see talented older students preparing to audition for professional companies. He’d tell his mentor, “I’m going to be just like them.”

But being like them takes years of physically grinding practice. “Dancing hurts,” Alvin Ailey once said. So dancers stock their rehearsal bags with rudimentary first-aid kits and physical therapy gear. Informational booklets for incoming college dance majors can include lists of local physical therapists, masseuses, acupuncturists, chiropractors and orthopedic surgeons.

Dancers, though, describe an insatiable, joyful passion for their work.

“You always pray that you will dance forever, and we know how impossible that is,” Faison said.

Credit: Tyson A. Horne

Much of professional dance is gig work. That makes it precarious. Get a contract for a certain number of weeks a year, then scramble to find extra work to fill in the gaps. Share an apartment, work second and third jobs as a store clerk or restaurant server, teach at studios and dance workshops. Median pay for a full- or part-time dancer is $21.64 an hour, according to the federal government. That’s somewhere between carpet installers and highway maintenance workers.

Every day is a test to prove your worth. At rehearsal. At auditions. Rejection is embedded in the terrain.

“Emotionally, it is hard,” said DeeAnna Hiett, who danced alongside Gerard, performed with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and now chairs the dance division at the University of Missouri’s Kansas City Conservatory.

When dancers line up in front of casting directors and choreographers to be judged, they try to be perfect. They strive to show their best side, their strongest leg. And, crucially, they work to hide any imperfections.

Gerard knew that drill. Not just in dance. In life.

Chapter IV

Don’t worry, Gerard told people. He was doing fine. But that wasn’t the truth.

When Gerard was young, maybe even before he was a teenager, he started using drugs. The abuse grew, though he tried to keep it hidden from the dance world.

A friend, who was about Gerard’s age and lived in the same apartment tower, said that by about 1985, she was his crack dealer. Crack was the same drug that would consume his mother.

Cheaper than the powdered form of cocaine, at that time crack was decimating communities around the nation, particularly Black ones. Users get a quick, intense high. The more they use it, the more they crave it. They’re trapped in a toxic net.

The former drug dealer recalled Gerard’s descent. To support his habit as a teenager and young man, she said, he offered himself for sex in downtown Paterson, along Broadway.

Paterson police officers arrested Gerard several times in the early 1990s, city records show. He was accused of prostitution after offering to perform a sexual act for $15. That was after the “Bad” video and working gig after gig.

Another time, he was picked up for having a white powder suspected of being heroin. And once, he was accused of stabbing his brother in the forearm with a kitchen knife on Christmas Eve morning.

Not all the charges stuck. Some were downgraded or dropped.

Armour, the Paterson neighbor who took dance lessons with Gerard, said he confronted his friend when he learned about the drug use. Gerard insisted he would get clean, that he didn’t need any help.

But when Gerard’s aunt visited the apartment that he had moved into in Paterson, she opened a closet door and saw a crack pipe on the shelf.

AIDS was an ever-present fear in Gerard’s personal and professional life. People in the dance community knew people who seemed fine, then, months later, would be dead. Gerard was 22 when he helped take care of his mother as she faced that fate. She died of AIDS at the age of 39.

He loved his mom, despite the upheaval she brought to his life, friends said. And he could relate to her addictions, though he perhaps thought he had a better handle on his own drug use.

He hit the New York City dance clubs hard. He was young and desirable.

“You always pray that you will dance forever, and we know how impossible that is."

He embraced a reputation in some dance circles as a party guy, a stylish vogue dancer and a sometimes drag queen. He could cause a stir when he showed up at auditions in New York. And he didn’t shy away from being out as a gay man.

At an audition for the professional Ailey Company in the 1990s, Gerard arrived dressed in what looked like top designer fashion. Ankle-length skirt pants. A crop top. Fur vest. Fabulous sunglasses and some fabulous bag. The goal was to exude success and hope reality followed the illusion.

Dancers and choreographers say his talents were easily up to Ailey’s standards.

Duane Cyrus danced in the Ailey and Martha Graham companies, two giants of the American dance world. He was a featured dancer in the original London cast of Disney’s “The Lion King” and now directs the University of Arizona’s School of Dance.

“Gerard was like a young, Black Baryshnikov,” Cyrus said. “In fact, he was better than Baryshnikov. He was in his own category.”

Credit: AP

But Gerard didn’t get the Ailey spot. Some wondered whether whispers about his drug use were costing him work.

He would later tell a friend he was fired from the set of another Michael Jackson video, “The Way You Make Me Feel.” He kept missing rehearsals and was having hallucinations. He thought his mental health was spiraling.

But he also believed that some people in the dance world weren’t choosing him for roles because they thought he was too effeminate and that his exceptional flexibility was too akin to that of female dancers.

Credit: Tyson A. Horne

De Jesus, who had first encountered him when they both auditioned for the “Bad” video, was mesmerized by Gerard’s looks, his flair, his dance skills and passion for the art. They began a long-term romantic relationship and moved in together in New York.

De Jesus would soon see there was another side to all that beauty. He said Gerard’s drug problems and his own drinking and strong personality were a volatile mix. Gerard would be loving and kind. Then nice Gerard would become not nice, De Jesus said. To buy drugs, Gerard would try to steal his partner’s money, leading to physical fights.

Sometimes, dealers in search of Gerard and the money he owed tried to break down the apartment door. Several times, De Jesus fled down the fire escape. More than once, he said, he came home to find that Gerard had emptied the apartment of everything of value, from designer clothes to TVs and furniture. Once, their dog was held hostage over a drug debt.

Dance gigs brought in money. But Gerard’s addictions quickly consumed it all. He and De Jesus could be out at a major event wearing Versace and Chanel, and later that night, Gerard would sell the outfits for money to buy drugs, De Jesus said.

As Gerard came down from binging on drugs, he’d often show up at his grandmother’s apartment instead of going home. She’d watch TV with him, cook his favorite, mac and cheese, and take out a photo album of him as a boy.

When De Jesus went to pick him up, Gerard would apologize for disappearing. He’d cry and say he wanted to die.

There were limits on how much help he would agree to, though. He occasionally went to Narcotics Anonymous meetings. But, as far as De Jesus knows, his partner never entered a broad rehab program.

Credit: Courtesy

Chapter V

Even with his drug abuse, Gerard could hide his problems and make dancing look effortless. Many people in his professional life didn’t know about his struggles.

He and De Jesus ended up in Ohio, dancing at the well-regarded Dayton Contemporary Dance Company. When De Jesus moved to Lakeland, Florida, between Orlando and Tampa, Gerard followed. But their relationship was fading and soon would come to an end.

Gerard got hired to dance in shows at Walt Disney World, including “Tarzan Rocks!” and “Beauty and the Beast,” according to friends and his bio. He was proud to be able to make a full-time living at dancing. He bought a house and a car. It required quilting together an array of gigs.

He taught dance classes and workshops, including summer programs in several cities for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. He did guest performances with the Georgia Ballet. He had lucrative engagements with a troupe in Japan every year. He danced and choreographed for dance companies in Florida. And he performed year after year with a regional dance company in Kansas City.

Hiett, who also danced in Kansas City, said Gerard’s ability to do anything and make it look easy wowed the crowd. “That is what makes audiences go, ‘Oh, my God! Did you see that young man on stage and what he just did?’”

His jumps still seemed to hang in the air forever. His beautiful feet still awed other dancers.

From the outside looking in, it seemed that years passed with none of the drug-fueled chaos that had sometimes marred Gerard’s life. If he was still using, he put on a good act.

In his personal life, he could dawdle, take too long to get ready and miss flights. But now in dance, he seemed like another person. He was disciplined and on time to rehearsals and meticulous about details. The goal was still to show perfection.

And there was a new, long-term romantic relationship. James Rosheger met Gerard at a dance club in Orlando. He was instantly captivated by Gerard’s smile and how easy he was to talk with. They shared a love of music, all kinds.

Rosheger is self-aware enough to know that he isn’t a good dancer. But Gerard made him feel free in a way he never had on the dance floor.

“No matter what I might do, however silly it seemed to me or to anyone else, he would grab a little part of that motion and begin doing it himself, which made me feel more creative.”

Then Gerard might riff off the dance moves of the people around them, and the good vibes would grow, Rosheger remembered.

“Gerard was like a young, Black Baryshnikov. In fact, he was better than Baryshnikov. He was in his own category."

He had heard some things about Gerard’s past with addiction. But it seemed distant. Gerard projected so much optimism, even if he was sometimes emotionally fragile. He could come to tears easily. Rosheger was struck by his partner’s ability to talk to anybody and encourage them. Even in private, Gerard wouldn’t speak poorly of people.

He loved to cook for visiting friends, kept his home immaculate and won compliments for his gardening skills.

Perhaps remembering his aunt’s words about making backup plans, Gerard started taking business classes to expand his career options. At the same time, he threw himself into dance. He talked often about the importance of documenting and preserving modern and ballet pieces choreographed and inspired by Black artists.

He headed out to Kansas City for weeks of rehearsals leading up to new performances with the Wylliams/Henry Contemporary Dance Company.

Nothing seemed out of the ordinary.

But, days before the first show, Rosheger got a call from members of the dance company. The words were chilling:

Come to Kansas City. Gerard has disappeared.

“The Dancer” Documentary

Watch the trailer below for the AJC’s short documentary on the life of Gerard Alexander, or see the full 30-minute film here.