Inside Georgia’s prisons, wave after wave of prison employees have become criminals themselves — smuggling in contraband or allowing others to do it and at times pocketing payoffs in the thousands, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation found.

Prisoners have run elaborate drug-trafficking networks and cybercrime schemes as well as extortion and other criminal enterprises, all with the help of the contraband supplied by dirty guards, nurses, cooks and even high-ranking officers. The widespread corruption has fueled violence inside the prisons and at times enabled stunning crimes victimizing people on the outside.

According to the state, outsiders, not employees, are largely to blame for contraband. Prisoners’ friends, family and gang associates are responsible for providing most of the phones, drugs and other prohibited items, Georgia Department of Corrections officials said.

Commissioner Tyrone Oliver said he has taken steps to identify corrupt staff since being named to the post in December. “Once we know that they may be compromised, and we get that information, we deal with it and we get them out of there,” he said.

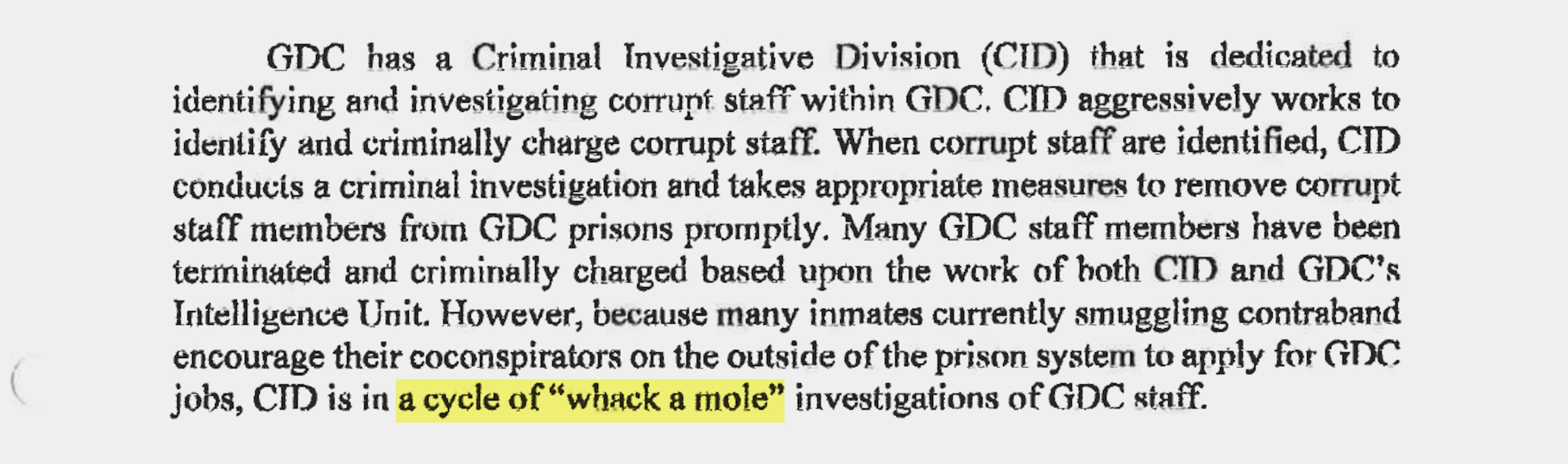

But the overwhelming dynamic facing the Department of Corrections is this: As fast as dirty officers are arrested, new ones take their places. That leaves the department, the state’s largest law enforcement agency, “in a cycle of ‘whack a mole,’” according to indictments earlier this year in a multimillion-dollar contraband scheme at Smith State Prison.

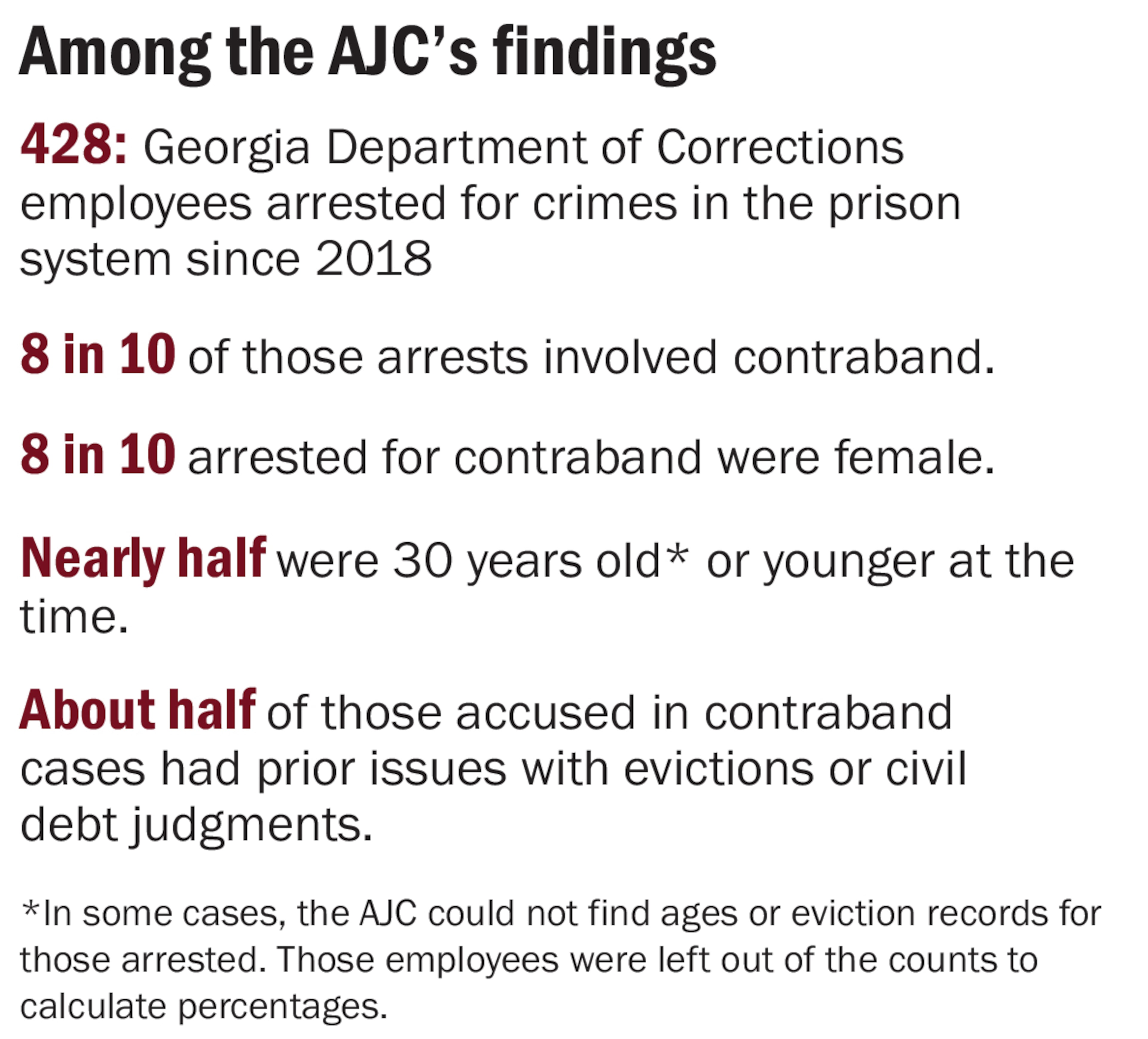

In its investigation, the AJC uncovered more than 425 cases in which GDC employees have been arrested since 2018 for crimes on the job. Some were charged with brutality, extortion or sexual assault. But most arrests — at least 360 — involved contraband. In 25 additional contraband cases, employees were fired but not arrested.

Some of those employees were paid thousands of dollars before they were caught in schemes that went on for months and even years, the newspaper’s investigation found. Those who were prosecuted rarely faced prison time. Some weren’t prosecuted at all.

In 2021 at Rutledge State Prison, a cellphone seized from an inmate showed a series of payments to a correctional officer, Promise Tucker. Confronted by the warden, Tucker admitted she would buy a can of tobacco for $40 and sell it to a prisoner for $500. A pack of Newport cigarettes, she said, could be sold for $200 to $250.

Asked by the warden how long she’d been smuggling in these items, she said she’d been doing it since she became a cadet 14 months earlier. She resigned in lieu of termination.

In 2019, a correctional officer at Calhoun State Prison, Temperess Johnson, was caught attempting to smuggle eight cellphones and a large haul of meth — 2.6 pounds — in a GDC van taking prisoners to medical appointments. She was due to receive $10,000, she told authorities. She was sentenced to five years in federal prison.

During a four-month period in 2018, Voltaire Pierre, a correctional officer at Hays State Prison, received $7,000 for bringing in pot, cocaine and meth in noodle soup containers. He was sentenced to more than eight years in federal prison.

“We have got a chronic, persistent issue in the state of Georgia of bad apples within the Department of Corrections doing all sorts of things. It’s a problem we’re dealing with every day,” said T. Wright Barksdale, a Georgia prosecutor whose district includes several prisons.

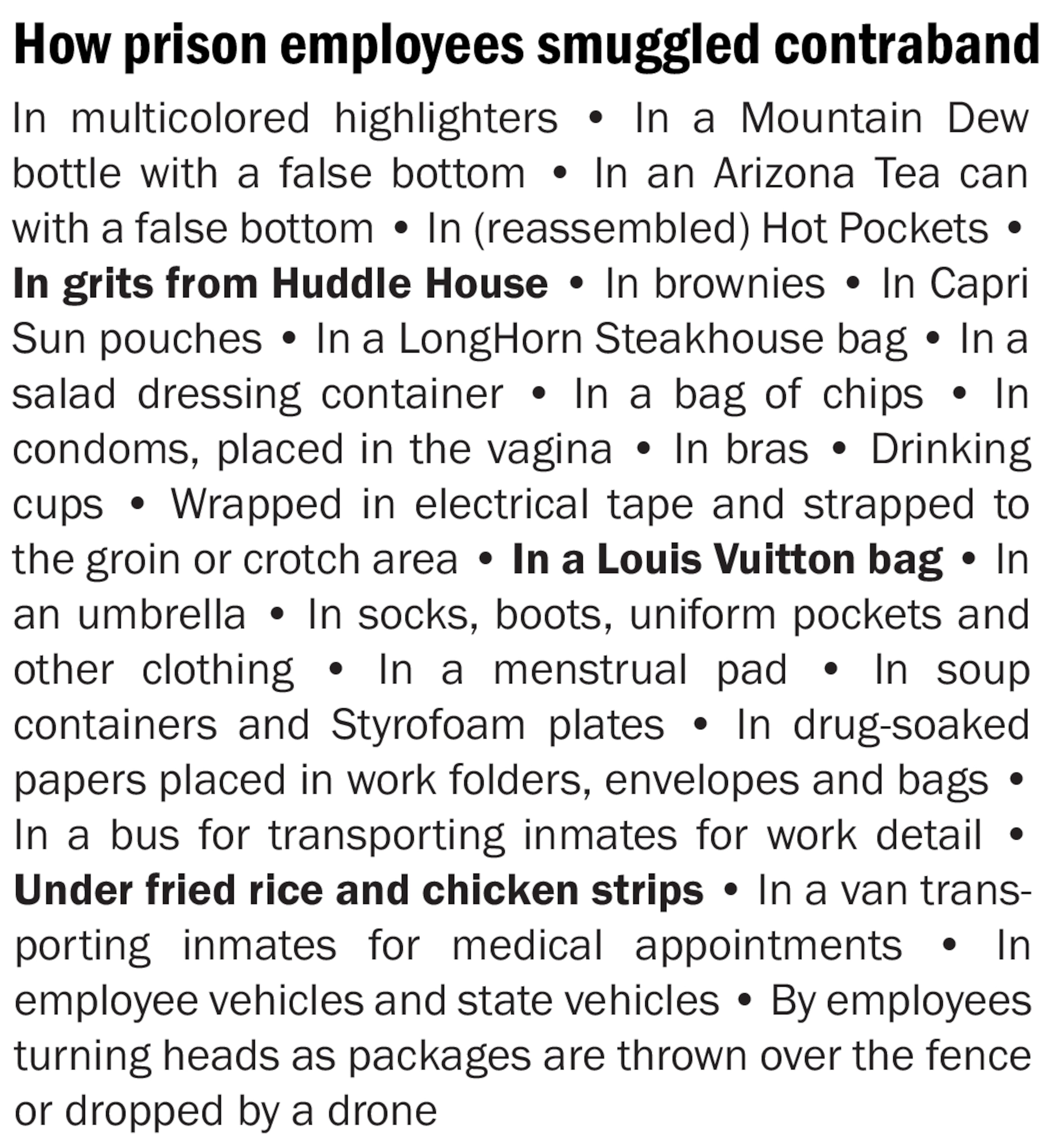

Correctional officers are sometimes corrupt on Day One, recruited by gangs to take prison jobs. In other cases, employees are enticed or coerced, once they are in the company of prisoners, into smuggling drugs and phones, issuing warnings about upcoming shakedowns, helping launder money, unlocking doors or looking the other way when drones drop contraband.

In truth, the environment created by the department makes corruption almost inevitable. Staffing levels are abysmal. Turnover is constant. Typical new officers are young women with no experience in law enforcement who are thrust into overwhelming jobs where they must contend with chaos and violence.

And many struggle financially. Despite recent salary increases, correctional officers in Georgia are paid less than those in many other states. Even Alabama, where the prison system has a history of low salaries and deplorable conditions, now pays significantly more.

Jose Morales, a retired Georgia prison warden, said he saw those circumstances play out when he was working in prisons across the state.

“When you’re making chump change, so to speak, and then these inmates offer you large sums of money just to bring in an item, and these are young, impressionable (employees, often with kids,)..., those factors add up to where they need more money to survive,” he said.

“And so, they take the bait.”

Hot Pockets and meth

The corruption within Georgia’s prison system is so pervasive, employees of all stripes — from cooks to lieutenants — are arrested on almost a weekly basis for moving drugs, phones and other contraband.

Over three days in January, four employees working at four different prisons were charged in contraband cases, the AJC found. Among those caught: the food service director at Central State Prison, who was alleged to have concealed pot and meth inside a bag of chips.

At Calhoun State Prison, the AJC found, since 2018 at least 19 employees have been caught bringing in contraband.

In one case, two officers tried to smuggle meth and tobacco stuffed into Hot Pockets packages. In another, a cadet brought a cooler containing cocaine and pot into a control room. In yet another, an administrative assistant tried to bring in more than a quarter pound of meth and was found to have more at the Econo Lodge where she had left her 10-year-old son.

Josh Hilton, the Calhoun County sheriff, said the prison’s remote location has always made it difficult to hire capable officers, even with state pay raises.

“Being in a less populated area in Southwest Georgia, the pickings are slimmer,” he said. “Most good, hard-working people are not going to quit their jobs to work at the prison. It’s a younger crowd, easier influenced.”

Most correctional officers want to protect the community and help people get better and return to society, said Hugh Hurwitz, a prison management consultant and a former acting director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. But working in a short-staffed prison — as most prisons in Georgia are — can create an environment conducive to smuggling contraband, he said.

Officers might be working double shifts, making it more likely they will miss or overlook things, or people with dubious qualifications might be brought on board to fill the schedule, Hurwitz said. “In every field, you have got some people that really don’t belong there,” he added. “But when it happens in corrections, people’s lives are on the line.”

An ongoing federal prosecution focusing on the flow of drugs in and out of South Georgia prisons reflects the scope of the problem.

According to the government, the operation was controlled by the Ghost Face Gangsters, a white supremacist gang. It extended to at least 10 South Georgia counties, both inside and outside prisons. Among those implicated: an officer who seemed to be the face of how well a career with the GDC could go.

Desiree Briley was just two years out of high school when she started in 2016 as an officer at Telfair State Prison. She was promoted to sergeant in 2020, then began training for greater responsibility as a K-9 handler. On her Facebook page, the 26-year-old mother of two proudly shared each of her steps upward, responding to one post: “I promise I’m not going to let nobody down.”

But even she was corrupted. In August, Briley was sentenced to 18 months in prison after pleading guilty to her role in the massive drug trafficking network. For at least two years, the investigation found, Briley helped a prisoner, James Dylon NeSmith, smuggle meth into the prison and distribute it.

NeSmith, serving a life sentence for murder, began dealing drugs when he entered the prison system, to provide money for his family, his attorney, Justin Maines, told the AJC.

Although Operation Ghost Busted, as the government dubbed it, is a sprawling case, Maines said the dynamics of it aren’t unusual. The former state prosecutor said he has learned from dealing with multiple clients through the years how easily contraband flows into prisons with the help of correctional officers.

“It’s so ubiquitous, it’s like sand on the beach,” he said.

$31 million in the bank

Even in the state’s most secure facilities, serious money has changed hands as officers have done the bidding of prisoners.

At the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison, which includes the state’s execution chamber, officer Vera Jackson admitted in 2018 that she was paid to provide a man on death row with information on upcoming shakedowns and on the staff.

Jackson told GDC investigators she received several thousand dollars to serve as a lookout for Eric Perkinson, who was sentenced to death for the 1998 killing of Dunwoody High School student Louis Nava.

Jackson ultimately was charged with receiving MoneyGram payments of $320 and $100 from two of Perkinson’s acquaintances on the outside. She resolved the case by pleading guilty to violating her oath as an officer and received five years’ probation as a first offender.

Morales, the retired warden, last worked with the GDC as the warden at the Special Management Unit, which houses many of the system’s toughest prisoners. There, he discovered the cellphone Arthur Lee Cofield Jr. used to steal $11 million from the Charles Schwab account of billionaire movie executive Sidney Kimmel. Morales said the phone showed the 31-year-old Cofield, incarcerated since he was a teen, had amassed $31 million in a bank account.

Morales said Cofield claimed he could pay as much as $10,000 for phones. Morales said he suspected certain employees were smuggling phones for Cofield but never caught them.

The Cofield case typifies what’s happening within the GDC today, according to Morales, who spent 22 years with the department after retiring from the U.S. Army. Morales said that when he first started, the jobs were competitive. Not anymore. Even with recent pay increases, he said, it’s hard to find qualified candidates for prison work.

“GDC is not filled with loyal, caring, professional, hardworking (employees),” he said. “Now, there are some, but a lot of them are low-level; they just need the job. They’re there for the paycheck and not willing to do what it takes to run it correctly and safely.”

Young and vulnerable

In case after case, the AJC found, those who crossed the line were women no older than 30. Many had evictions, bankruptcies and other signs of financial difficulties in their past. Few had anything close to law enforcement experience.

How did they get hired? The requirements for prison officer training in Georgia are minimal: a high school diploma and a criminal history that doesn’t include felonies. Unlike the federal prison system, the GDC doesn’t research the credit or financial histories of its applicants, the AJC learned.

Some female officers questioned in the cases examined by the AJC weren’t motivated by money. They portrayed themselves as friends or even soulmates of the prisoners for whom they’d provided contraband.

At Baldwin State Prison, 22-year-old Natalian Andrews was hired as a correctional officer in 2018, though her previous work experience was as a sales associate at Walmart. Nine months later, she was fired for smuggling in a small amount of marijuana in her bra for a prisoner on his birthday.

Andrews told a GDC investigator she was the mother of a 1-year-old trying to make it on her own and that Montavious Wingfield, serving a 15-year sentence for armed robbery, had helped her at a low point in her life. She said she regretted “falling for him,” according to the investigator’s memo.

Andrews was charged with crossing the prison’s guard line with drugs and violating her oath as an officer, but the charges were dropped after she provided evidence that she’d received mental health treatment, court records show.

Other cases revealed more complicated scenarios, indicating the women had long known the men they were dealing with — possibly before the women were hired — and that money was indeed involved.

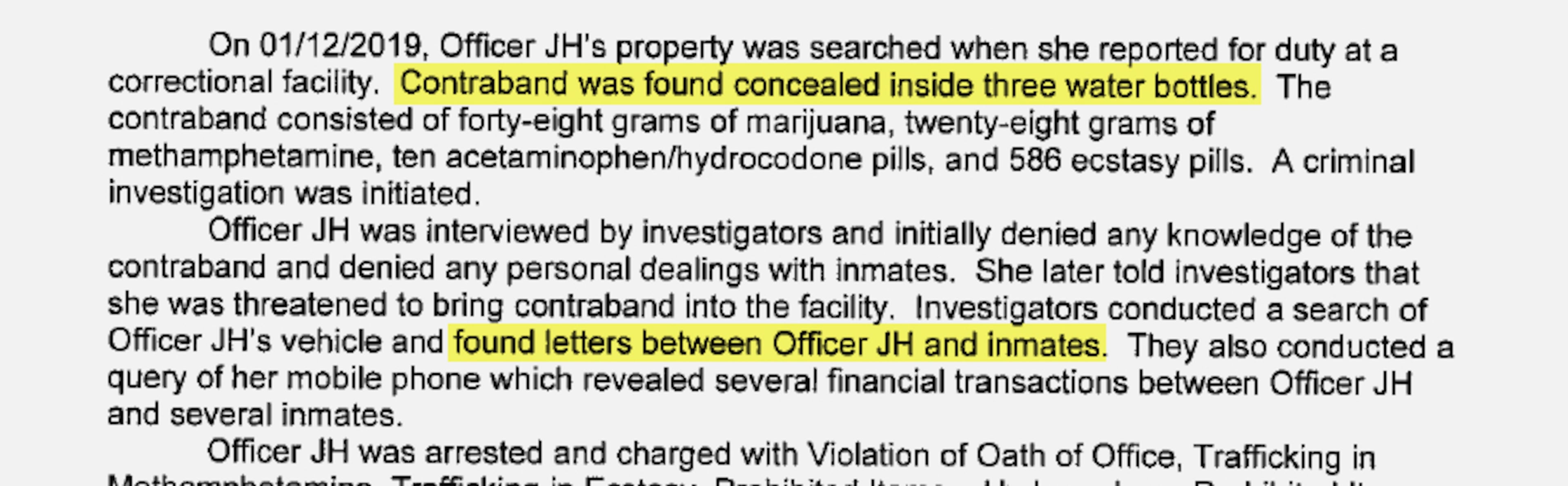

Jasmine Nicole Hall had been an officer at Hancock State Prison for just seven months when, in January 2019, she was caught at the entrance with three Aquafina water bottles with the seals broken and the liquid discolored. The bottles were found to contain compartments filled with meth, pot, ecstasy and hydrocodone.

Hall, whose previous job was as a package handler at a FedEx facility in Hapeville, told a departmental investigator that she’d gotten the bottles from a woman she didn’t know in a Walmart parking lot and had agreed to deliver them to the prison for $3,000. She said it was her first attempt to smuggle contraband.

But when investigators analyzed a phone found in Hall’s vehicle, they discovered evidence she had a relationship with a man incarcerated at Macon State Prison and that the pair had been working together to distribute marijuana and phones throughout the prison system. Photos suggested the pot was being stashed in Capri Sun pouches. The data showed 35 transactions totaling more than $5,000 with friends or family members of inmates in eight different prisons, almost all identified as gang members.

The GDC report on the phone analysis identified the prisoner at Macon State Prison as Brandon Cantrell, a member of the Gangster Disciples known as “Jihad,” who at the time was serving a 20-year sentence for armed robbery and robbery by intimidation.

The report also noted that Hall had a “Jihad” tattoo on her left ring finger.

Hall, 28, ultimately pleaded guilty to possession of meth with intent to distribute and was sentenced as a first offender to 20 years’ probation and 180 days in a probation center. The AJC could find no record of a wider criminal prosecution involving Cantrell or others based on the cellphone evidence.

No one is immune

In the past year, no story has hit the GDC harder than the scandal at Smith State Prison, where investigations of murders outside the prison and a sprawling contraband scheme inside led to the arrest and dismissal of the warden, Brian Adams. He is charged with violating Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, bribery, making or writing false statements and violating his oath as a public officer.

Warrants for Adams’ arrest say he received U.S. currency through a pattern of racketeering activity associated with a massive contraband scheme known as the Saint Laurent Squad, headed by a Smith State Prison inmate, Nathan Weekes.

Over the past year, Weekes and his associates have been charged with three murders related to the contraband operation, which used Cash App, Western Union and cryptocurrency to bribe officers and purchase all manner of contraband, including marijuana and meth, jewelry, weapons and luxury clothing.

While a warden’s arrest is rare, others in leadership positions have been caught up in contraband schemes, showing that even the department’s better-paid employees sometimes can’t resist temptation. The AJC found at least a dozen other officers holding ranks of sergeant or above who have been arrested or fired since 2018 for their roles in contraband cases, with at least one now serving time in a GDC facility.

“When you have what sounds like rampant and pervasive misconduct by staff, and particularly when it reaches up to a fairly high level in the administration, you have a culture where the people running the prison don’t understand themselves to be bound by rules and aren’t taking seriously their basic obligation to keep people safe,” said Aaron Littman, an assistant professor at the UCLA School of Law and the faculty director of UCLA’s Prisoners’ Rights Clinic. “That is profoundly toxic for everyone involved.”

One of the higher-ranking officers caught up in the corruption was Lakeshia Thomas. She was a lieutenant at Hays State Prison when the Georgia Bureau of Investigation in 2019 uncovered evidence that she was arranging to bring in marijuana for Jarico Deshun Brown. A member of the Gangster Disciples known as “Goon,” Brown is serving a sentence of life plus 15 years for the 2014 execution-style murders of two men in Coweta County, one of whom was a former jailer.

In a phone conversation with Brown monitored by the GBI, Thomas indicated that she knew what was in a package she was bringing in for him and indicated she knew it was risky.

‘...You trying to have me doing fed time, like for real,” she told him, according to a court filing.

Brown then asked whether she could handle it, “like we normally do.” Thomas responded: “Uh, yeah, but I’m gonna have to wrap it though, so I’m sure ain’t nothing smelling.”

Thomas, 44, has been incarcerated at Pulaski State Prison since pleading guilty in April 2022 to possession of marijuana with intent to distribute and violation of her oath as an officer. Her sentence runs 15 years, with two to be served in confinement.

A similar case played out at Baldwin State Prison in 2021, when it was discovered that Lt. Tracey Wise had been smuggling papers laced with K-2, a synthetic form of marijuana, for a notorious gang member.

Wise, 45, had been a prison guard since 1999 and had just been promoted to lieutenant when his contact information was found on a phone confiscated from prisoner Ryan Brandt. The phone showed that Brandt and Wise, identified as “Lakers,” had been in contact with each other 155 times.

Brandt has been in prison since he was sentenced by a Gwinnett County judge in 2007 to a then-record seven life sentences for a violent home invasion in Snellville, as well as other crimes. Inside the prison system, he has been identified by the GDC as a high-ranking member of the Sex Money Murder branch of the Bloods.

Questioned by a GDC investigator, Wise acknowledged that he brought in the drug-laced papers for Brandt three times, folding the papers in his pocket “like paperwork,” and receiving $2,500 each time. He subsequently pleaded guilty to violating his oath as an officer and was sentenced in November to five years’ probation as a first-time offender.

In his interview with the GDC investigator, Wise said he agreed to smuggle the drugs because he needed the money. Even with a part-time security job at a Macon hospital on top of his $52,000 state salary, he was struggling to keep up, he said.

“My home note (was) behind, my car note (was) behind,” he said. “And I had so much going on that I didn’t know what to do and how I was going to make it.”

It endangers everyone

Widespread corruption and contraband in a prison system mean rehabilitation and recovery remain elusive.

People whose crimes were fed by addiction may stay on drugs. People who leave prison, as most do, can come out more schooled in criminal behaviors.

“Placing somebody in a facility where there’s rampant, serious crime being committed by the people running the place is not exactly a promising way to rehabilitate someone,” said Littman, the UCLA professor.

What’s worse, violent people can continue to be violent, committing assaults and murders inside prison and orchestrating violent crimes that play out in communities.

Oliver, the GDC commissioner, acknowledged that contraband is the “driving force” for the violence inside the state’s prisons, as well as the violence that spills over into the outside world.

Georgia prosecutors in districts with multiple prisons have joined that chorus, saying they are overrun with cases related to prison corruption and violence.

“GDC is not filled with loyal, caring, professional, hardworking (employees). Now, there are some, but a lot of them are low-level; they just need the job. They're there for the paycheck and not willing to do what it takes to run it correctly and safely."

Barksdale, the district attorney for the Ocmulgee Judicial Circuit, said his office has as many murder cases stemming from attacks in the prison system as it does murder cases in his communities. Understaffing is a particular problem, he said. Many sentenced to prison join gangs and get weapons because they realize the few people working can’t ensure their safety, even if they want to.

“We’ve got a serious, serious problem,” he said.

Armed with contraband phones, prisoners can also continue to create violence on the outside, and those cases are perhaps the most disturbing examples of the GDC’s failure to fulfill its mission to protect the public.

One community continues to deal with the fallout from a prison-related murder. In Glennville, the home of Smith State Prison, Bobby Kicklighter was a beloved 88-year-old history buff, widower, Korean War veteran and retired civil servant. In 2021, he was shot to death in his bed in the middle of the night.

The community was stunned. Later, when investigators announced they had solved the crime, citizens in the South Georgia town were even more unnerved.

The GBI determined that Kicklighter’s murder was a case of mistaken identity. The intended target: a correctional officer at Smith State Prison who investigators believe was cracking down on contraband. And, the investigation determined, the killing was a “hit” orchestrated from inside the prison by Weekes, who headed the contraband operation that Adams, the warden, had aided.

The murder investigation unearthed a web of wrongdoing and resulted in the bribery charges against Adams.

Weekes is now facing the death penalty and is charged in two other murders tied to his contraband operation. Two former correctional officers have also been implicated in the murders. One ended up murdered herself, a killing that prosecutors say Weekes ordered.

According to indictments, Weekes bragged about his ability to continue to carry out crimes in spite of being in the GDC’s custody. In videos filmed inside the prison and posted on social media, the indictments state, Weekes proudly declared the motto of his squad.

“Shit don’t stop cuz the (expletive) door locked.”