Credit: Courtesy of Mary Pat Henry

Courtesy of Mary Pat Henry

The Dancer: An unexpected finale

Mary Pat Henry had heard the rumors.

But over the nine years that Gerard Alexander performed with the Wylliams/Henry Contemporary Dance Company, she had never seen signs of his drug abuse. If anything, he often seemed more poised than others.

Henry, the company’s co-founder and artistic director, remembers when a choreographer had an unusual idea. It involved dancers incorporating big exercise balls into a performance.

In rehearsals, dancer after dancer crashed to the floor, bashing knees and elbows, while attempting to gracefully glide from atop one ball to the next. Not Gerard.

He looked like a swan floating over the balls, Henry said. “It was so easy for him and so hard for everybody else.”

He did that often.

It seemed he could do anything and convince fellow dancers they could, too. You got it, cookie, he reassured partners. Let’s do it.

To the public, he wasn’t a big-name star. But in dance communities, many knew him or had heard of him. Most weren’t aware of the untreated trauma from his New Jersey youth, the scars of sexual abuse and a mother who was addicted to crack.

He usually was good at concealing the bad stuff. At a young age, he began using street drugs, relying on his exceptional talent to help him hide that secret.

Some compared him to Mikhail Baryshnikov, one of the most admired male ballet dancers in generations. Gerard traveled the world performing as a ballet, modern and jazz dancer.

Yet he later would end up homeless on the streets of Atlanta.

Credit: Courtesy of Mary Pat Henry

Chapter I

Gerard was 19 years old when he earned a coveted spot dancing in Michael Jackson’s hit music video “Bad.”

Some two decades after the King of Pop’s blockbuster, Gerard was still stitching together enough work to make a full-time career in dance.

One of his regular gigs was with Wylliams/Henry in Kansas City, where he would stay for weeks at a time, rehearsing for upcoming shows.

It was during one of those stints that he went AWOL.

Days before a big performance, he went out to dinner with other dancers, then made some stops at local clubs. At some point, he separated from his friends.

That night, Gerard didn’t make it back to the home where he was living while working in Kansas City. He didn’t return the next night either. And when it was time for rehearsal, he didn’t show up or answer his phone.

Credit: Courtesy of Mary Pat Henry

The people at Wylliams/Henry grew frantic. They called the highway patrol, then hospitals in Kansas City and St. Louis, where they thought he might have gone.

Was he safe? Was he alive?

Two of the dancers used to privately refer to him as “Bambi,” because they thought his openness and gentleness made him vulnerable in a harsh world.

The decision was made to call Gerard’s partner, James Rosheger. Come to Kansas City, he was told. Gerard has disappeared.

Meanwhile, the company’s director had the upcoming show to think about. Gerard was, as always, one of the lead dancers and was scheduled to appear in numerous pieces.

“I thought, ‘What are we going to do?’” Henry recalled.

She had to figure out how to rework the show without him.

Then two dancers driving down a main strip in Kansas City saw a disheveled man walking along the sidewalk.

Wait. Was that Gerard?

They pulled over and ran to him. He was shirtless, in flip-flops, and appeared to be wearing the same brown pants he’d last been seen in about a week earlier. He didn’t look right. He was clearly unbathed and sweating profusely. Anyone who didn’t know him might have thought he was homeless.

The women urged him to get in the car with them. He refused.

I’m OK. I’m OK, he said, crying.

One of the dancers gave him her cellphone to keep, pleading with him to call his boyfriend. He didn’t.

The women drove away, feeling helpless.

Rosheger flew to Kansas City to look for his partner. He couldn’t fathom what was happening. When he heard about the sighting, he went to a nearby spot and waited.

Hours passed. Then he caught sight of a bedraggled figure walking down the street: Gerard.

“I rushed out and I embraced him,” Rosheger recalled.

Gerard was distant at first. Rosheger had to coax him to a hotel room for food and a shower.

Fellow dancers wanted to come see him; Gerard couldn’t bear the thought. Instead, he and Rosheger flew home.

Later, Gerard would blame the episode on the stress of trying to sell a house he owned in Florida, making a move to Atlanta and preparing to perform before an audience that expected perfection.

Rosheger said it was the only time in their four-year relationship that he had witnessed real drug abuse by the man he loved.

Henry said she hadn’t seen any warning signs. Dance companies knew Gerard had drug problems years earlier, she said. “But they also knew he was such a worthwhile human being, and he was such a beautiful dancer.”

Choreographers were enamored with his grace and control, as well as the supernatural pliability of his feet and toes. Were it not for the drugs, Henry said, Gerard would have been “one of the very best dancers in America.”

But she concluded he couldn’t remain with the company.

“I lost the faith that he could have stayed clean. I thought, ‘I can’t do this again. It’s too hard.’”

Chapter II

Gerard had slipped in the past.

Years earlier, when he lived in New York City, he would disappear for days on drug binges.

I’m escaping. I’m getting away from myself, he told his partner at the time, Ferdinand De Jesus.

“He would show up in my apartment looking like a homeless person who didn’t have anybody who cared about them. It was almost like he punished himself. ... Like, ‘I have to get food out of the trash. I don’t deserve for people to love me,’” De Jesus said. “What in the world does that to somebody?”

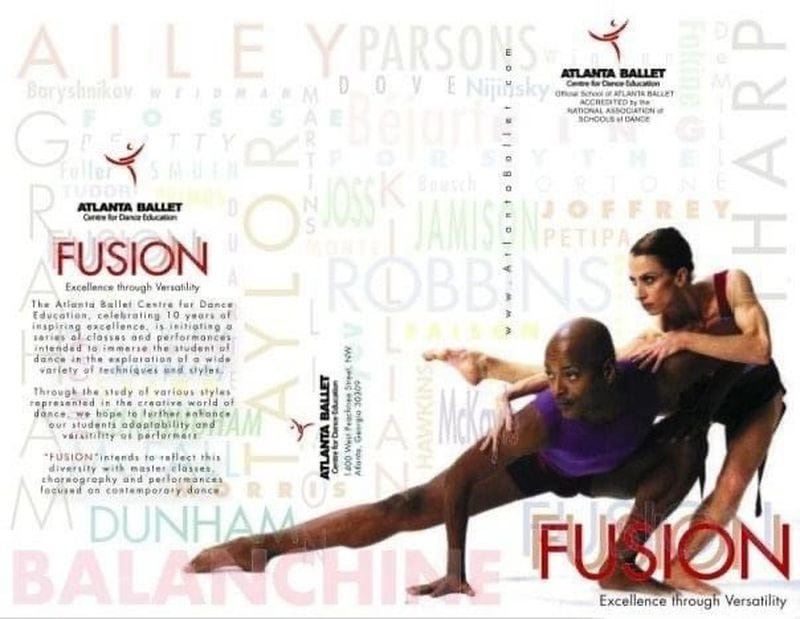

Credit: Atlanta Ballet

De Jesus urged him to get therapy. As far as he knows, Gerard never did.

But Gerard always seemed to regain his footing. Professionally, he kept finding opportunities.

In 2006, the Atlanta Ballet offered him a job teaching dancers in disciplines other than ballet. He bought a condo across the street from the ballet center’s Buckhead studios, and he and Rosheger moved in.

“The students loved him,” said Sharon Story, dean of the Atlanta Ballet’s Centre for Dance Education. “He was just so positive and very knowledgeable.”

Gerard, then in his late 30s, hoped for a fresh start. He sounded optimistic, as he almost always did, Rosheger said.

Every day, he set aside time to stretch his amazing feet and legs, instruments he meticulously maintained.

Lonnie Davis, who had danced with Gerard in Kansas City, often met him for an evening glass of wine. From the back deck of Gerard’s Buckhead condo, they’d dream up ideas for how to expand modern dance offerings in Atlanta.

Through the Atlanta Ballet, Gerard organized a special summer program called Fusion. It was to culminate in a big performance by the students.

Then the troubles reappeared. The day of the show, Gerard couldn’t be found. Parents and dancers didn’t know what to do. He finally arrived long after the show was supposed to have started, acting as if nothing was wrong.

Davis came to a depressing realization: “All these dreams and plans we had for building the dance community and making an impact here, Gerard is not the person I can do this with.”

Chapter III

Despite the optimism he displayed to others, Gerard’s life was crumbling. His partnership with Rosheger ended. So did the job with the Atlanta Ballet. He had become less dependable, his boss said.

In early 2008, Gerard’s grandmother, the woman who raised him, the comforter he always turned to in difficult times, died. He traveled to his hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, for her funeral and carefully did her makeup and hair just the way she would want.

He didn’t tell family members about his troubles in Atlanta.

Back at home, he was falling behind on paying bills. So Davis, who worked as a casting agent, got Gerard modeling gigs at trade shows and conventions. Certainly, the man who could perform soaring leaps could handle a job that required little more than sitting.

Credit: Facebook

But Gerard would show up incoherent or would fall asleep during assignments. Davis got a call from his boss: You can’t book Gerard anymore.

To keep his car from being repossessed, Gerard hid it. Around the end of 2010, he lost his Buckhead condo. Then came a scattering of local arrests on a scattering of drug charges.

Most of his friends and family remained largely unaware of his growing problems. But it became increasingly difficult for Davis and others to get in touch with Gerard. When they did reach him by phone or text, he did what he had learned how to do in front of casting directors in dance: He hid the imperfections. Masked the flaws.

Occasionally, someone from the dance world might run into him around the city.

Late one night, Davis spotted his old roommate near a Midtown gas station. He pulled in to say hello; Gerard seemed to have trouble recognizing him.

Days later, Davis got a voicemail: I’m going to try to bounce back, Gerard said.

Another dancer was so shaken after happening upon Gerard — wandering Atlanta’s streets, incoherent and dirty — that she burst into tears.

“We felt so helpless,” Davis said, “because we didn’t know how to reach him. He just faded away.”

Rosheger brought food and money when he met up with Gerard at the Lindbergh Center MARTA station. Gerard refused to disclose anything about his circumstances or where he was living. Only when the conversation turned to dance did he brighten.

Word was starting to travel. One of Gerard’s childhood friends passed along, through another friend, that Gerard could share her two-bedroom apartment in New Jersey. He never called.

“We felt so helpless, because we didn't know how to reach him. He just faded away."

Gerard did ask an aunt, Betty Alexander, if he could bunk at her home, a one-bedroom apartment in his Jersey hometown. But the senior citizen feared her nephew would steal from her.

She told him she had learned he had swiped Christmas presents from his beloved grandmother years earlier to fuel his need for drugs. He didn’t argue, as the aunt recalled. He just hung up.

“He never wanted to really disappoint me, and he knew he had.”

Gerard kept trying to put up a front for others. Jerome Nuney Stigler, a close friend and fellow dancer, remembers getting a quick call from him. Gerard said he was doing fine.

Stigler told Gerard to call if he needed anything. He shrugged off the offer.

I’m great. I’m great, Gerard said. If I need anything, I’ll let you know.

But he didn’t.

Credit: Hyosub Shin/Hyosub.Shin@ajc.com

Chapter IV

At some point — exactly when is unclear — Gerard began living at tent sites hidden by trees near the intersection of Atlanta’s Buford Highway and Lenox and Cheshire Bridge roads. Once a global traveler, his world shrank to a couple of miles around the crossroads on the fringe of Buckhead, the same toney community where he had owned a condo.

The dancer who had been compared to Baryshnikov rummaged for scraps.

Don’t take all the good stuff, he told one newcomer beside a dumpster, his voice, as always, theatrical and high-pitched, with precise enunciation and an “up North” accent. Let me in on some of that.

Gerard fished out cut flowers that still had a bit of color and paintings that had been tossed away. He enjoyed painting himself, if he could find the right supplies.

He was described as a camp mom for other homeless people, mostly men, living in tents and pieced-together shelters. He set up warming fires and used the food he got from nonprofits to cook for them: spaghetti, goulash and, once, they swear, a cake.

He shared clothes he had gathered. He’d let people crash under a tarped area that served as his outdoor living room, near his tent, which was like a bedroom.

Credit: Courtesy

The homeless encampments can be dangerous, unsanitary, painfully cold, oppressively hot, mosquito-ridden and cruel. Drug dealers and pimps are often present. Friends will share what little they have or sometimes steal from one another. Those who live on the streets long enough are likely to witness crimes or be a victim of sexual assaults or other violent attacks. Addictions and serious mental health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder, are common.

Many who live in the encampments want to be with others who wrestle with the same issues and aren’t likely to judge. It’s a partial respite from shame. But the camaraderie can be both a comfort and an enabling curse.

Before Trey Nelson got clean from meth and off the streets, he would dumpster dive with Gerard. There were days when Nelson would be in anguish about all the mistakes he’d made. Gerard had words of advice: You just have to live every moment and every day and try to find something that makes you happy.

Credit: Contributed

One source of Gerard’s happiness was Charlie, a little, black-and-white mop of a dog who was his constant companion. He doted on the dog, wheeling him around for strolls in an old-fashioned-looking baby buggy. If someone took Charlie or if the dog wandered off, Gerard would search until he found him.

In a note to caseworkers, he described the dog as his emotional safety net: “We both have separation anxiety.”

He also found respite in the sliver of nature near his tent. He staked out a strip of sand along a small, shimmering creek beneath the trees. On his tiny beach, Gerard would do dance stretches, or perform leaps and fan kicks.

Others who were homeless would stop by his campsite to visit throughout the day and into the evening. At night around campfires, loosened up by drugs, people would talk about their glory days. Gerard would regale friends with recollections about voguing and partying in New York City dance clubs.

Rarely would he talk about hard times. But occasionally, he let the veil slip.

“I do remember us having a conversation about what he could have been if he would have kept dancing,” Nelson said. “I believe that was the hardest thing for him to deal with mentally — to know what he had come to.”

Credit: Courtesy

Gerard told a caseworker he started taking meth to get a bounce of energy for his rigorous life as a dancer. What he didn’t disclose: In many ways, it was similar to crack, a drug he had been addicted to most of his life.

Like Gerard’s dance colleagues in Kansas City, caseworkers worried about his vulnerability on the streets. Some people who are homeless try to present a tough exterior. Gerard didn’t. He also faced health issues. He had hepatitis. He had been HIV positive for years and had to stick to a strict drug regimen to keep the virus tamped down.

A social worker also concluded he had symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder and PTSD.

Credit: Hyosub Shin/Hyosub.Shin@ajc.com

Chapter V

Credit: Courtesy of Tracy Woodard

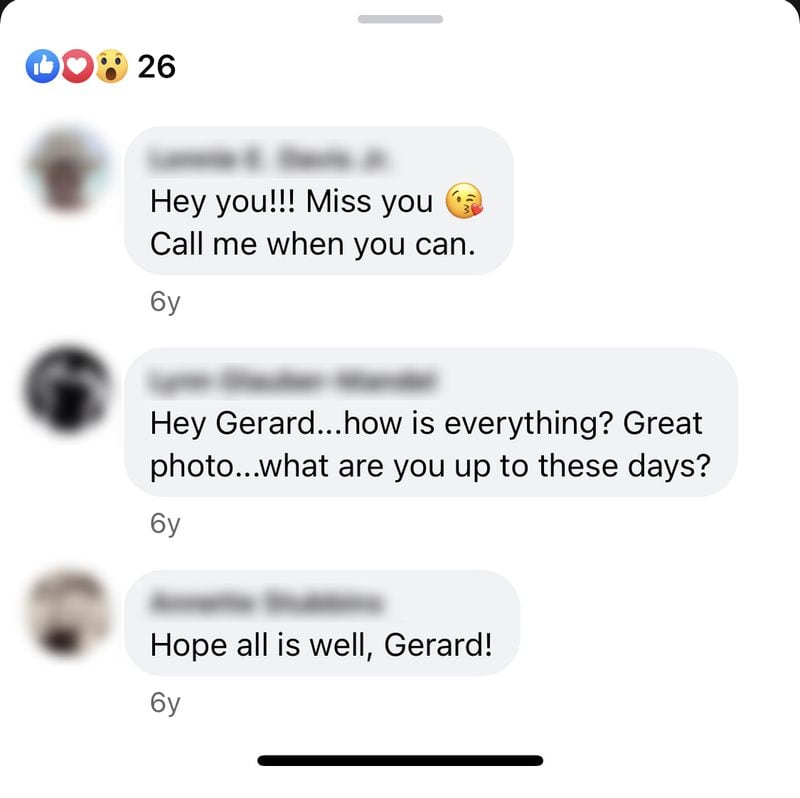

At the end of 2019, Gerard posted on Facebook what seemed like New Year’s resolutions: “Housing, health, job and putting a nest egg away for my future.”

His dance friends, spread around the country and often fooled by Gerard’s facade, likely didn’t realize how mighty those goals were.

It can be difficult for caseworkers to get housing for active addicts. Another issue for Gerard: Charlie.

Many programs at the time wouldn’t allow dogs in the units set aside for people coming off the streets. Gerard refused to leave Charlie behind or give him away.

Eventually, the dog disappeared for good. Gerard was crushed. He wept to caseworkers.

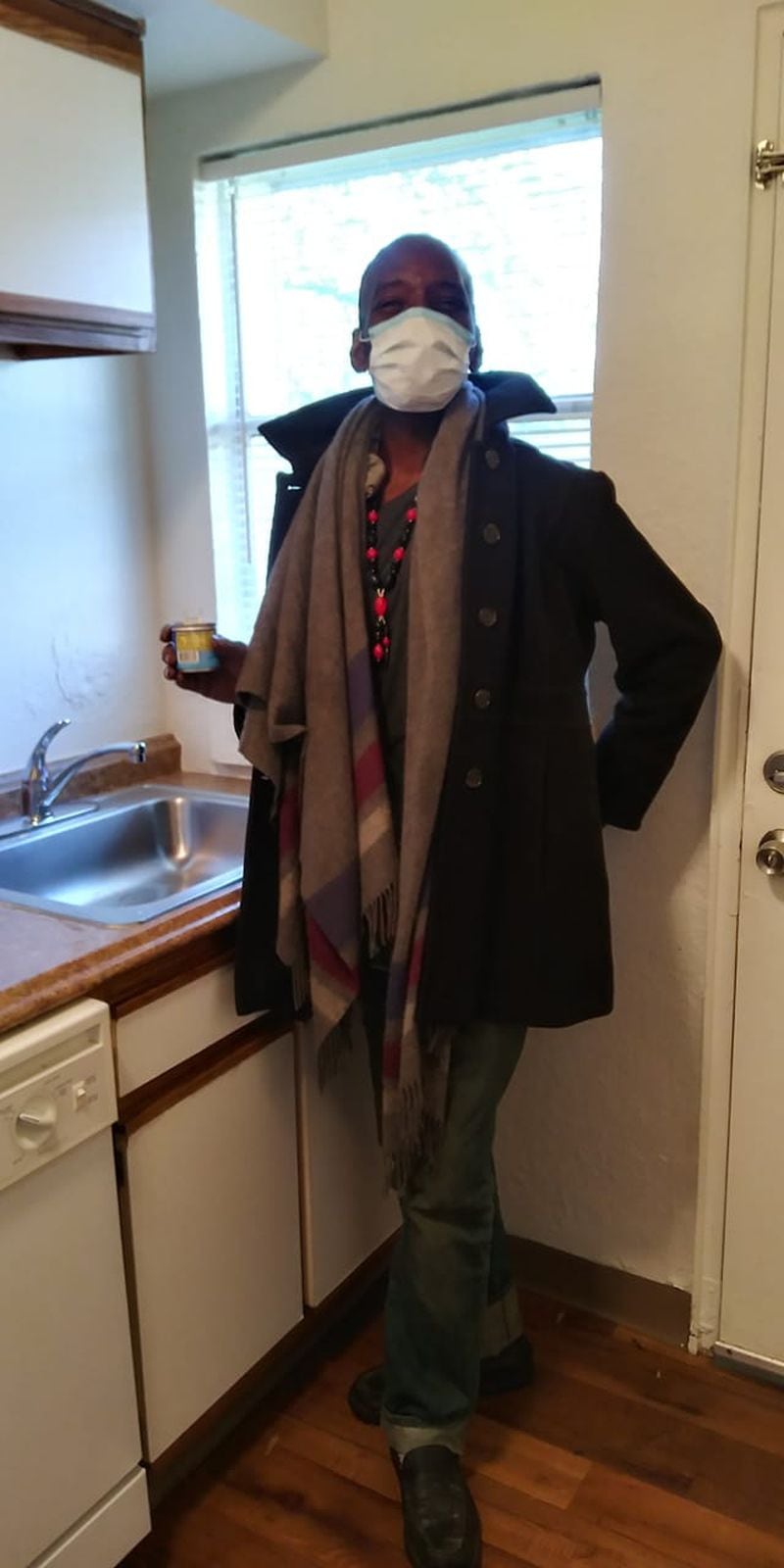

Just before Thanksgiving in 2020, caseworkers for the nonprofit Intown Cares found him an apartment, paid for with government funds. He seemed grateful to have a comfortable new place that nonprofits had outfitted with furniture.

Still, it was far from the people he had lived around for years.

“He was just incredibly lonely,” said Tracy Thompson, who founded the nonprofit Elizabeth Foundation and less than a decade earlier had herself been homeless. “He was ashamed for being homeless. He had disconnected from the rest of society.”

He had created a sort of family in the encampments. They watched out for each other. Grievous imperfections went largely unjudged.

Gerard started showing up again at the sites where his homeless friends were. He’d say he wanted to cook for them or make sure they weren’t lonely. While there, he would use meth, friends said. Sometimes, he would stay for days, sleeping once again in tents.

While out at the muddy encampments, Gerard’s extremities got cold and wet. That led to frostbite, said Tracy Woodard, a team leader for Intown Cares. It was the winter of 2021, a year after she had placed him in the apartment.

“They had to cut off all his toes,” Woodard said.

His beautiful feet. The feet that accomplished dancers and choreographers had been awed by.

“Oh, my God. Oh, my God,” said Henry, the artistic director in Kansas City, when she later learned what had happened.

“None of us knew this. I swear, we would have reached out to him. We didn’t even know where he was,” she said. The amputations “probably devastated him. Losing what your tools are, that is losing part of what makes you a dancer.”

Credit: Contributed

Chapter VI

Woodard witnessed the aftermath. “He was in terrible, terrible pain.”

At first, he was without any real medical follow-up care or support system, caseworkers said. He would crawl on his hands and knees around his apartment. He couldn’t get to a laundromat to clean his clothes and tried unsuccessfully to wash them in his dishwasher. He couldn’t clean up after himself.

“It was one of the saddest things I’ve ever seen,” said Thompson, of the Elizabeth Foundation. “And I’ve seen a lot of sad things.”

The man who had once amazed people with his otherworldly leaps, who took care of other people, couldn’t walk or care for himself. He mourned losing his independence.

In a Facebook post, he blamed the loss of his toes — and some fingers — on complications from diabetes.

A doctor “assured me I would still walk but to consider sharing my gift/talents in arts/dance with” people who are disabled, he wrote. “Learning a whole new way and a whole different way of life especially when I’m forced to embrace the life that God has continued to bless me with.

“As I still try to wrap my head around this one day at a time, I look forward to creating what and where my life will turn out to be.”

Recuperation was gradual. Doctors fitted him with a special boot, and he regained some halting mobility. And, again, he began visiting the encampments.

Gerard sometimes acted as if the loss of his toes was a novelty. But a friend at the camps recalled what Gerard had quietly shared with him: “It destroyed him.”

As the months passed, Gerard continued to leave his apartment to live among the homeless for days at a time.

Chapter VII

Last year, on April 25, Gerard’s 55th birthday, Atlanta emergency dispatchers received a 911 call.

“I am walking on Cheshire Bridge Road underneath I-85,” the caller said, “and I believe there is someone, like, maybe dead underneath, in the rocks, underneath the bridge.”

The body was sent to the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s office.

Gerard was dead. Shot seven times, including once through the heart, according to an autopsy report. The document includes a passing mention of the amputated toes. Meth was detected in his system.

Based on descriptions from the autopsy, it appears Gerard might have been dead for days before his body was found beside the busy Atlanta road. Investigators collected seven shell casings near his body, which had been wrapped in comforters and blankets.

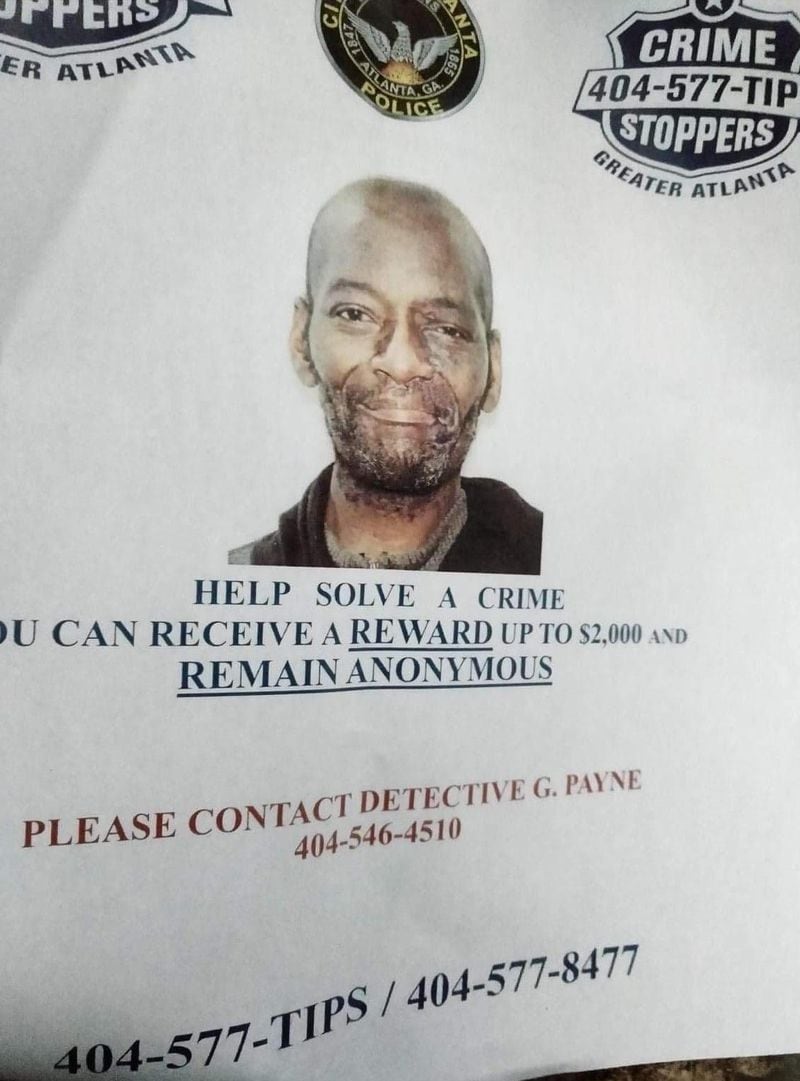

Credit: Crime Stoppers of Greater Atlanta

More than a year has passed since Gerard died. Atlanta Police said recently that the investigation is ongoing but would not provide details.

People who lived in the encampment say they can’t understand why anyone would kill Gerard. They believe he posed no physical threat, had nothing of value to steal and wasn’t likely to cause trouble for anyone. Several didn’t learn until after he died just how exceptional his dance skills were, how high his career had soared and how great his potential had been.

Woodard, who helped Gerard get the apartment, posted a photo of him on a remembrance wall for people who had died. She didn’t know about his past, all of its promise and pain. She knew him as a kind and gentle person who helped those around him and died, maybe alone and afraid, in the dirt under an Atlanta interstate.

Friends in his former life still wonder why he couldn’t ask for help. Many were shocked when they saw a flyer about the crime. It included a recent photo of Gerard before he died. He looked so old and beaten down. How could that be the same person they knew, the one who had been so vibrant on the stage, so stunning in photos?

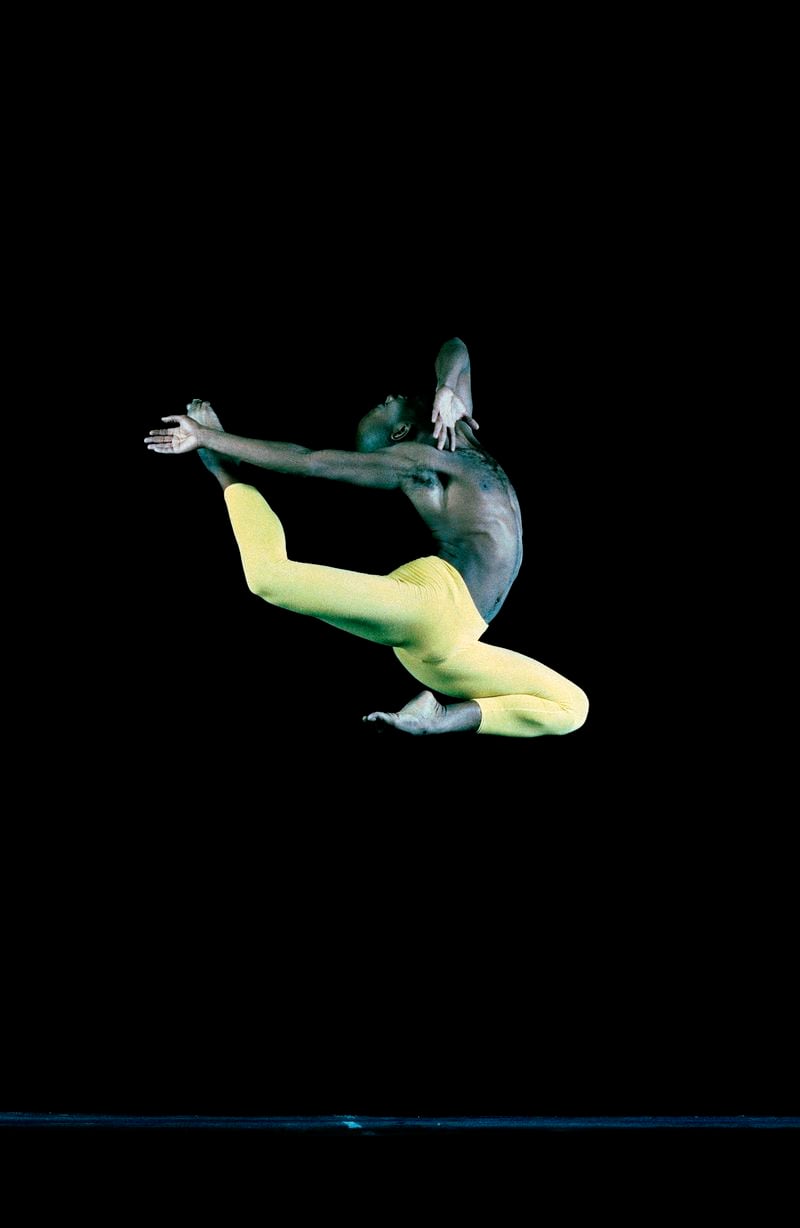

Joanne Savio, who photographed Gerard when she co-authored “Vital Grace: The Black Male Dancer,” thought a good bit about his death. “You hope there is something good from this. Some kind of lesson. Something to learn ...”

Savio recalled working closely with Gerard and other dancers during the book’s photo shoots in the late 1990s.

“I’m a clumsy person. One of the pleasures for me was they could do things I couldn’t imagine doing,” she said. Watching Gerard, she could vicariously experience it. Even today, looking at the images, she’s wonderstruck.

“Whoever killed him,” she said, “had no idea this man could fly.”

Credit: Photographer Joanne Savio, choreographer Duane Cyrus

“The Dancer” Documentary

Watch the trailer below for the AJC’s short documentary on the life of Gerard Alexander, or see the full 30-minute film here.