Georgia leading nation in new juvenile lifers

An AJC investigation highlights an opaque and fragmented sentencing process that is out of sync with the rest of the nation.

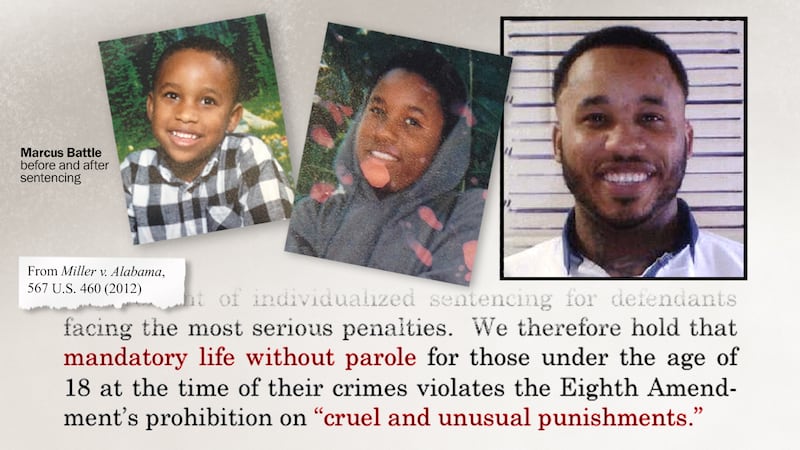

After sentencing Marcus Battle to life without parole, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Stephanie Manis took a brief moment to acknowledge the tragedy.

“It breaks my heart,” she told the packed courtroom.

Earlier that day, a jury had convicted Battle, then 20, and two other defendants of murdering a stranger during a 2012 armed robbery in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Capitol View. While the transcript from the sentencing hearing shows Manis was troubled by the defendants’ young ages — bringing up their youth multiple times — she ultimately chose the harshest possible sentences.

Battle, the youngest, had been 18 when the incident happened, she had been told. When Fulton County’s DA requested the maximum punishment possible, the judge obliged with a life-without-parole sentence: Battle, a pudgy youth with slack shoulders and a faint stutter, should die in prison.

“That’s what justice demands,” Manis said at the September 2014 sentencing hearing. “And that is a fair sentence.”

There was just one problem: Battle’s trial attorney had incorrectly stated he was 18 at the time of the incident. In truth, he had been six days shy of his 18th birthday.

Those six days meant a world of difference in the legal arena. At 17, Battle deserved a special level of consideration before being sentenced to life without parole. Two years earlier, in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a mandatory life-without-parole sentence was unconstitutional for young people convicted of murder. The decision, which cited brain differences between adults and youths, stopped short of banning the sentence outright. But, it maintained that when dealing with a juvenile — what the court defined as someone under 18 — the sentence amounted to cruel and unusual punishment and should be reserved for the rarest of cases where a youth was deemed irreparably corrupt and beyond rehabilitation.

Simply put: The Fulton County Superior Court system had bypassed the fact that Battle had been part of a malleable and highly-studied cohort of defendants that the high court — over several decisions — had determined should be treated differently than adults.

“He was sentenced to life without parole without the proper procedures,” said Mark Loudon-Brown, an attorney with the Southern Center for Human Rights who discovered the error in 2019 and promptly contacted the Fulton County prosecutor’s office to flag the mistake.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he later added.

Given the 2012 decision (Miller v. Alabama) and a subsequent 2016 ruling (Montgomery v. Louisiana) that made the ruling retroactive, Loudon-Brown felt confident that the resentencing would be fairly straightforward. Battle, he thought, was a few crossed t’s and dotted i’s away from a parole-eligible sentence.

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Fast-forward four years and Battle is still locked up for life.

While the Fulton County District Attorney’s office acknowledged the clerical error and agrees Battle deserves a new sentencing hearing, its recommendation — even now knowing he’d been a kid — remains the same.

“Murder is murder,” Deputy District Attorney Adam Abbate explained at a February 2021 court proceeding, outlining the county’s stance before Judge Robert McBurney, who has yet to rule on the request for a new sentence.

“It’s not fair to treat one murderer different from another because of six days or three years,” Abbate continued. “Here we’re talking about loss of life and that doesn’t change whether you’re 13 or 52 when you commit a crime.”

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court stressing that age and circumstances do matter when considering punishments, the Fulton County District Attorney’s office is insisting otherwise. Battle, now a sinewy 28-year-old with a sleeve of tattoos and the same faint stutter, should, they argue, still die in prison.

“They reconsidered it,” said Atteeyah Hollie, deputy director of the Southern Center who, alongside Loudon-Brown, is representing Battle, “and landed in the same place.”

While Hollie is quick to point out her disappointment with the prosecutor’s recommendation, she is not surprised. Battle’s story may seem like a single miscarriage of justice due to an error at a trial. The prosecutor’s response, however, highlights bigger, more systemic issues, according to the defense attorney.

“Marcus’ case,” said Hollie, “is an example of what you’re seeing statewide.”

“(Marcus Battle) was sentenced to life without parole without the proper procedures. ... I couldn't believe it."

Georgia has seen a 100% increase in its number of juvenile lifers — young people, under 18, sentenced to life without parole — since 2012 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the sentence should be reserved for the rarest of cases, an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has found.

The increase is placed in juxtaposition with the rest of the country, which is moving away from the most severe punishment. Today, 28 states, plus the District of Columbia, have banned juvenile life-without-parole sentences, according to Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a D.C.-based nonprofit advocacy group. An additional five states still permit the punishment but have no juveniles currently serving the sentence.

“We haven’t seen this happen in any other state,” said Rebecca Turner, an attorney with the advocacy group, who tracks juvenile lifer data across the country.

“It’s pretty clear,” she later said, “that the pace at which Georgia has imposed this post-Miller doesn’t reflect meaningful consideration or a reflection that youth matters.”

To better understand the status of juvenile lifers in Georgia, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution combined a mix of Open Records Requests, news archive searches, emails and interviews with county prosecutors and judges to create the only current and comprehensive database of young people sentenced to life without parole before and after the 2012 Miller decision.

The data — which was compiled in the absence of such tracking by the Georgia Attorney General’s office, Georgia Department of Corrections and the State Board of Pardons and Paroles — highlights an opaque and fragmented sentencing pattern, one that is out of sync with the rest of the nation and impacting individuals incarcerated before and after the 2012 ruling. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s investigation identified six trends:

- A national outlier: Georgia leads the nation in juvenile lifers sentenced over the past decade. Georgia is the only state to sentence more young people to life without parole after Miller restricted use of the harsh sentence than before. The state has sentenced 31 young people to life without parole since 2012. Six have since appealed and received life with the possibility of parole. Of the roughly 100 juvenile lifers sentenced nationally over the past decade, more than half are in Georgia and Louisiana, which is second in the nation during that period, according to Turner’s advocacy group.

- The state is flying blind: Georgia officials can’t accurately say how many juvenile lifers are or have been in the state’s prisons. The state has no reliable mechanism for tracking juveniles sentenced to life without parole. In more than one instance, the AJC identified individuals who were either incorrectly labeled as juvenile lifers or missing from official lists. The lack of data threatens the constitutional rights of some defendants and makes it more difficult to oversee and hold accountable local courts who may be misusing the harshest available sentence for juveniles. It also means the Georgia legislature has incomplete data when considering laws that impact the criminal justice system.

- Geography and judges matter: Since 2012, Richmond County, which includes Augusta, has sentenced six young people to life without parole, the highest number of any county in the state. In one instance in Richmond, the prosecutor’s office recommended that a teen get life with parole, but a judge ruled against this suggestion and gave life without parole.

- Race matters: Of the 31 young people sentenced to life without parole in Georgia since 2012, 25 — or 81% — are Black. This is an increase from the pre-Miller numbers when 60% of the state’s juvenile lifers were Black.

- Impulsivity dominates: While the high court said life without parole should be reserved for rare instances, an AJC review involving the 31 defendants sentenced after the 2012 ruling found that roughly half of the cases stemmed from incidents that could be categorized as armed robberies and carjackings or reflected spontaneous acts of gun violence. While disturbing — as all homicides are — these episodes, juvenile advocates say, often reflect environment, upbringing and impulsivity rather than forethought or advance intent. They typically don’t represent the rare circumstances the high court said the punishment should be reserved for, and ignore the fact that these young people are supposed to be uniquely capable of change. In one 2016 incident out of Columbus that led to a life-without-parole sentence, for example, the victim was shot in the leg during a robbery and died of a blood clot 11 days later.

- Nobody has come home: In 2016 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Miller should be retroactive and juveniles who had been sentenced to die in prison before 2012 should have the chance to be resentenced and go home. Yet nearly a decade later, not a single person sentenced before 2012 has been released in Georgia, except for one whose conviction was reversed for unrelated reasons. Of 11 individuals who got new, parole-eligible sentences, nine have gone before the parole board, and each has been denied parole. For a comparison, Michigan, which had the second-highest number of juvenile lifers, has seen over 180 juvenile lifers (over half of the total) go home already. According to Turner, nationally there were roughly 2,900 juvenile lifers when the Miller decision came down and about 35% have been released.

In response to the fact that no pre-Miller defendants have gone home despite being eligible for parole, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles stated that decisions come down to “public safety” and “risk of reoffending on an individual case-by-case basis.”

“Age at the crime commit date is undoubtedly a significant factor but isn’t and shouldn’t be the reason to release an individual into the community,” Steve Hayes, the parole board’s communications director wrote in an email, adding: “Even though these 11 individuals are now parole-eligible the Board has determined their release from custody at this time is not compatible with the welfare of society.”

Credit: Houston Co. Sheriff's Office/Ga.

Hayes would not give details on the rationale for each individual denial.

The Georgia Department of Corrections said its systems are not designed to track juveniles who receive life without parole, and agency officials see no reason to track that separately from adults who receive the sentence.

“We have no role in determining whether their life sentences were imposed properly,” said Joan Heath, a spokeswoman for the agency. “Their sentences are valid unless and until the trial court, an appellate court or a habeas court tell us otherwise.”

Several local prosecutors across Georgia defended their recommendations when it came to cases involving juveniles sentenced after the Miller decision. Some pointed to a 2021 U.S. Supreme Court decision that watered down some of the language around Miller by letting a judge give out a life-without-parole sentence without having to state on the record why a juvenile is irredeemably corrupt -- something that was expected previously.

The Georgia Legislature has determined it is an appropriate sentence under certain circumstances and prosecutors are within their right to seek the sentence if those factors exist, said Pete Skandalakis, the executive director of the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia, who said he was surprised by the data the AJC had compiled but was unable to draw any conclusions.

“I think it’s tragic that all these are serving life sentences or even life without parole, but that doesn’t negate the fact that the judge may have found the factors that he or she had to sentence somebody to life without parole,” he said.

The Fulton County District Attorney’s Office did not respond to multiple emails and voicemails regarding Battle’s sentence and their other case recommendations.

The disjointed interpretations of the law, coupled with the previously unreported data, have meant Georgia has emerged as a surprise battleground in a war many assumed to be over.

“We have a lot of states where we have Republican champions who really, really believe in the power of redemption and positive changes of youth and offering second chances to folks,” said Turner, pointing to Texas, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah and Arkansas, which all have banned juvenile life-without-parole sentences.

“And then,” she continued, “you have Georgia just moving in the opposite direction of all of this momentum.”

Evolving views of juvenile crime

The modern understanding that children and adults are biologically different dates back over 100 years when, in 1904, psychologist G. Stanely Hall wrote his two-volume book “Adolescence.”

Defining the phase of life as a period of “storm and stress” he argued that adolescence was brought on by both environmental factors and the physiological changes of puberty. Kicking off at age 11 and mellowing by 24, the period, he explained, was marked by a “curve of despondency” where young people are more risk-taking, more prone to mood swings, and more apt to resist adult authority. Males, specifically, he said, saw an uptick in aggression and sensation-seeking during this period.

Hall wrote that adolescence “is when the very worst and best impulses in the human soul struggle against each other.”

While the term adolescence stuck, what has been less straightforward during the past century is how society would respond when young people acted out or committed crimes. Did they deserve rehabilitation or punishment?

Georgia opened its first juvenile court in 1911 in Fulton County, a move that reflected Hall’s thesis and specifically focused on catering to developmental distinctions. Rooted in the Latin concept of parens patriae (parent of the nation), the courts viewed young defendants not as criminals but as children who needed help. The state, as a guardian, was responsible for redirection.

Over time, however, lawmakers began to chip away at the boundaries and conditions that defined a child and in turn what accountability should look like.

The year Battle was born — 1994 —the United States was in the middle of “get tough on crime” debate that led to a wave of legislation that argued children should be prosecuted and treated as adults.

“These are not the Cleaver kids soaping up some windows,” Gov. Zell Miller said during his State of the State in January of that year.

While Georgia already had a 1971 law on its books that treated 17-year-olds as adults in the criminal justice system, that day Gov. Miller outlined new crime legislation that would require children as young as 13 to be tried and prosecuted as adults in Superior Court if they committed certain violent crimes like rape, murder and aggravated battery.

“These are middle schoolers conspiring to hurt their teacher,” he continued, “teenagers shooting people and committing rapes, young thugs terrorizing whole neighborhoods and then showing no remorse when they get caught.”

The issue would reach its apex in 1995 with an article by a Princeton University criminologist that declared that a group of juvenile “super-predators” were a danger to America’s cities. He predicted a continuing rise in crime perpetrated by a new breed of young people who were more violent, ruthless, and remorseless than those of the past.

“These are middle schoolers conspiring to hurt their teacher, teenagers shooting people and committing rapes, young thugs terrorizing whole neighborhoods and then showing no remorse when they get caught."

Subsequent studies disproved the idea, which was criticized for being racist, and the academic who came up with the term even expressed public remorse that he had advanced a damaging theory that did not prove true. But by then much of the age-redefining had been done. Georgia was one of 49 states that had passed laws making it easier to try — and sentence — young people as adults.

Miller v. Alabama, in many ways, was a reaction to this reaction.

As the juvenile “super-predator” theory was debunked and the pendulum swung back toward a rehabilitative view, cases began making their way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Attorneys questioned how harsh sentences — where kids were prosecuted as adults — aligned with the growing body of science and research that showed, much like Hall’s early work, that young people were cognitively different from adults.

In 2005, the high court took this biological fact to its logical conclusion: Young people are categorically less deserving of society’s severest punishments.

That year, they ruled that sentencing anyone under 18 to the death penalty was unconstitutional because of these developmental differences.

Five years later, the justices reiterated these findings, ruling that juveniles could not be sentenced to life without parole for crimes that did not involve murder. The opinion stressed, again, that young people are impulsive, prone to peer pressure, and most importantly, well-equipped for rehabilitation.

Homicide was addressed in June 2012 with the Miller decision, and then reiterated in 2016 with Montgomery, which made Miller retroactive.

Mandatory life without parole, the justices explained in their opinion, should be reserved for “the rare juvenile offender whose crime reflects irreparable corruption.”

Going forward, when a sentence of life without parole was to be considered, judges and juries, according to the high court, should take into account “youth” but also characteristics like home life and the circumstances of the crime. These have subsequently been labeled “the Miller factors.”

Georgia’s unlikely relationship with juvenile lifers

While Georgia had been marching in lock-step with the rest of the country when it came to introducing harsh sentences during the 1990s, it was something of a statistical surprise when it came to life-without-parole sentences during this period. When the Miller ruling came down, advocates estimated that there were nearly 3,000 “juvenile lifers” nationwide; fewer than 1% were in Georgia.

Without context, the state’s low numbers could be misinterpreted as an outgrowth of some sort of prescient reforms. In reality, it was due to the fact that it was tied to the most severe punishment — the death penalty — and came with a slew of rigorous requirements.

Up until 2009, Georgia had a law stating that a life-without-parole sentence could only be handed down if a prosecutor was seeking the death penalty. This meant that from 2005 — when the Supreme Court banned the death penalty for juveniles in Roper v. Simmons — until 2009, the sentence was off the table to give to juveniles. And prior to 2005, it was doled out sparingly; few district attorneys sought the death penalty because it is expensive, time-consuming, and difficult to argue, according to Steve Reba, an attorney who co-directs the Appeal for Youth Clinic at Emory Law School’s Barton Child Law and Policy Center.

Reba became something of an expert on the state’s small cohort of pre-Miller juvenile lifers in 2013 when he successfully argued before the Supreme Court of Georgia that anyone sentenced to life without parole before 2005 had an impossible sentence, and therefore should get resentenced.

“We argued that Roper should apply retroactively to all those individuals,” said Reba. “You’re not eligible for death, therefore, your life-without-parole sentence is invalid.”

This meant that when Montgomery came down in 2016 making Miller retroactive, many of Georgia’s juvenile lifers had already been resentenced to a parole-eligible sentence.

Yet, despite the unexpected three-year head start, not a single individual has been released.

“Someone may become eligible, but it doesn’t mean they’ll ever get parole,” said Reba, noting one of the unspoken truths in the fight over juvenile lifers: Getting a client a parole-eligible sentence is just the first hurdle. In Georgia, it does nothing to actually promise a return home.

“(The parole board) sends you back a letter that says ‘due to the nature of your offense you’re being denied parole.’ And it’s like, well, that’s a problem because the nature of my offense is never going to change,” Reba continued, contending that he believes such denials miss the point of the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings on juveniles. The crime, while forever tragic, is static and will never change. It is the person — the juvenile — who is thought to be uniquely capable of change.

This reality has created an interesting — and debatably unexpected — dynamic in the state.

While Georgia’s stunted pre-Miller numbers, coupled with Reba’s 2013 work, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions should have meant the state would be a national leader when it came to low juvenile lifer numbers, the opposite has, in fact, transpired.

Instead, the state has a small cadre of pre-Miller juvenile lifers who have been resentenced but remain in prison because they’ve been denied parole time and again, and a host of new, young defendants who are being given a punishment the majority of the country has banned.

“If they were in a different county in Georgia, or maybe even more so a different state in this country,” said Hollie, “they probably wouldn’t have gotten this sentence.”

A childhood marked by instability, struggle

Battle had lived in six different ZIP codes by the time he was 12. Miles apart, they still had basic similarities: high rates of poverty, struggling schools and regular interruptions of violence.

“When you grow up in the hood you witness a lot of stuff,” said Battle’s mom, Sandra Reese, on a sticky afternoon this summer from her wood-paneled bedroom in Jonesboro.

The third of 10 children, Battle had a childhood plagued by many of the hallmarks that tie poverty to trauma, circumstances the high court believed should be considered when determining if a kid should die in prison.

His dad was out of the picture, incarcerated on drug charges. Reese — who is now sober — was in and out of court-ordered drug rehab programs. When Battle was in the fifth grade, he was removed from the household and spent a year in the state’s foster care program.

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Joseph Isagba, his foster father during that year, remembers Battle as a quiet and respectful child who followed the rules. He was surprised and sad to learn of the trajectory of Battle’s life after leaving their care.

“I have good memories of Marcus,” said Isagba.

In 2005, Battle returned to his birth family. It was comforting to be around his siblings and loved ones, but he wonders how things would have played out had he stayed away.

“It was a gift and a curse,” Battle said through his attorney, Hollie. “Because maybe if I stayed in foster care, maybe I wouldn’t be in this situation. But it felt good being around the woman who had me.”

At home, Battle resumed his duties as man of the house as he entered the sixth grade.

“I really didn’t have a lot of help,” said Reese, a warm 56-year-old who speaks with disarming candor and the same wide smile as her son.

“He’d stop by McDonald’s, make sure everyone had food. Make sure everyone ate, that everyone was good,” she said, remembering how Battle, who she calls Mark, would try to pitch in.

While Reese is clear on certain details and memories from Battle’s childhood, others — like when exactly he stopped going to school — she struggles with.

“Mark began to act out, more than drop out,” she said, finally remembering that it had been during the ninth grade. “They kept suspending him, and that made him not want to go.”

From the start, Battle’s schooling experience was a challenge. In elementary school, according to Reese, he was prescribed stimulants to concentrate. These made him drowsy, so he stopped taking them.

In 2009 Battle’s middle school — Parks Middle School — was ground zero for cheating, which later led to the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal. He had been in seventh grade at the time.

Credit: Miguel Martinez

By high school, Battle had fully checked out. Trips to the principal’s office and suspensions became the norm. He lost motivation.

So one day in 2011 — in the middle of his freshman year — he just stopped going.

At this point the family was living in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Atlanta and Battle had begun spending time with a crew of older boys in their late teens and early 20s that Reese believed were a bad influence.

One year later, 19-year-old Kenneth Roberts Jr. would be dead, and Battle would be arrested and charged in the homicide. Two of the older guys from this new crew would be his co-defendants. While Battle had gotten in trouble for things like trespassing and joyrides, this would be the first felony on his record.

According to court records, Battle and some of his new friends were hanging outside of a convenience store in September 2012 when one said he had just seen a gas station patron with jewelry and money in his pocket, and asked if anyone wanted to go rob the stranger. Battle agreed to go along.

The defendants, according to prosecutors, opened fire “when one of the victims made a sudden move” during the armed robbery. One bullet fatally struck Roberts and two others were left severely injured.

The scene was tragic, as every juvenile lifer case is. A person lost their life due to senseless violence. It was also chaotic.

On top of the victims getting injured, one of Battle’s co-defendants was shot. Court testimony indicated that the individual shot himself when trying to put his gun back into his waistband.

Battle, according to the transcript, was in possession of a gun. It was not, however, the weapon that delivered the deadly shot, according to ballistics evidence presented at the trial.

“It does not make anything OK, obviously, that Mr. Battle was out there. But again, asking you to look at things on a spectrum,” Jason Green, Battle’s court-appointed attorney said at the 2014 sentencing hearing, later stressing his client’s transient immaturity. “There is no evidence before the court to indicate he would not be able to be rehabilitated and, at some point in time, after serving his penalty to society, to be back out.”

“He’s young,” Green added, not knowing just how young his client had been. Or, more specifically, the review he was entitled to under Miller.

For Battle, the trial was a confusing and isolating experience. He didn’t have a fancy lawyer, institutional backing, or family to navigate the legal system. Reese, who was struggling financially, had moved in with family in Alabama at the time. She couldn’t afford to make it back for the proceedings.

As in so much of his childhood, Battle was both surrounded by tons of people and also completely alone. Once he got to prison he felt even more alone.

“I knew I was on my own now,” Battle said through his attorney. “It changed my life. Knowing you’re behind a fence for the rest of my life, it changed my life.”

The Jones effect

In February 2021, Battle was once again alone in a courtroom. This time he was incarcerated and calling in via Zoom to a courtroom in Fulton County Superior Court. Judge Robert McBurney wanted to get up to speed on the case and to know what was being requested as far as a new sentencing hearing.

During the proceeding, Abbate, the prosecutor, made clear the county’s intentions to request continued life without parole, calling Battle “irreparably corrupt.”

Ultimately the prosecutor never spoke to what specific evidence he was referring to, and two months later a U.S. Supreme Court ruling came down that said he did not have to: a ruling that has further complicated the debate over whether Georgia is following the intentions of the high court on life-without-parole sentences for juveniles.

In April 2021 the Supreme Court clarified Miller and Montgomery with Jones v. Mississippi. The opinion, written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, stated that judges do not have to prove a youth is irreparably corrupt when handing down a life-without-parole sentence; they simply have to take into account a young person’s age.

The ruling, according to Turner with the Campaign for Fair Youth Sentencing, didn’t have a broad impact across America, especially as so many states have done away with the sentence altogether. In Georgia, however, the decision further empowered prosecutors and judges to utilize a life-without-parole sentence with minimal explanation.

While the state was already sentencing young people to life without parole at a quick clip post-Miller, this has accelerated in the two years since Jones. Seven young people have been sentenced to life without parole since the 2021 ruling.

“(Miller’s) underlying framework is still in place,” said Turner. “But (Georgia) just said, ‘OK, like, none of these considerations are really necessary,’ which was somewhat unusual.”

Numerous prosecutors and judges that the AJC reached out to turned to the logic of the Jones decision when questioned about their office’s recommendations and sentences of juvenile lifers after 2012. They did this even in cases where the sentencing decision was made before 2021.

While previously they would be held to the five Miller factors, now many prosecutors and judges in Georgia feel comfortable simply pointing to the heinousness of a crime as an explanation for their recommendation or sentence.

“[Miller's] underlying framework is still in place. But (Georgia) just said, ‘OK, like, none of these considerations are really necessary,' which was somewhat unusual."

Superior Court Judge Ashley Wright said she was not aware that Richmond County, which is under her jurisdiction, had sentenced the most juvenile lifers in the state.

“This is not a metric that I have been tracking,” she wrote in an email. “But if true, it would likely mean that there are a lot of young people committing the most serious offenses like murder, rape, armed robbery, hijacking, and kidnapping.”

For defense attorneys, this reality is frustrating and a step backward.

“As long as we continue to make the offense itself the chief indicator of whether someone should be sentenced to life without parole you’re gonna have outcomes like (these),” said Hollie of the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Differing views of past troubles

Jones — and its deeply different interpretations between defense attorneys and prosecutors — highlights one of the biggest issues in Georgia when it comes to juvenile lifers: different views of how a youth’s background, including criminal history, should be weighed in deciding appropriate punishment.

Take, for example, Jayden Myrick, another Fulton County juvenile lifer who was sentenced to life without parole last year. At age 17, Myrick fatally shot a wedding guest outside a Brookhaven country club during a 2018 armed robbery.

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Myrick, who had been the subject of a previous AJC investigation into juvenile detention facilities, had a father in prison and a mother who struggled to raise him alone. At 13 he was first arrested for a fight at school, and soon after, he was in and out of the state’s juvenile detention facilities.

When he was ultimately sentenced it was determined that his tough history, gang affiliations, and time in and out of facilities were seen as aggravating factors.

But defense attorneys and juvenile advocates see it differently. If the state’s juvenile detention facilities lacked rehabilitative qualities and exposed Myrick to more violence, then, they question, wouldn’t that experience be a mitigating factor?

Myrick testified at his trial that he was groomed and pressured into joining a gang at 9 years old. Less than a decade later, his life in the outside world is over and he, as it stands now, will die in prison.

“We failed. It’s our failure. It’s definitely our failure, and it’s our responsibility that he then went out and killed somebody because we didn’t take care of it properly,” said former Fulton County Superior Court Judge Wendy Shoob.

Hollie similarly questioned how a teenager under the watch of the state is shouldering, alone, this trajectory.

“There’s very little inquiry and very little analysis of how (kids) were born, or grew up, in systems that exposed them to more violence and more trauma with little education and little therapy and treatment,” she said.

Data gaps hamper Georgia’s system

Georgia’s use of the life-without-parole sentence for juveniles is complicated by the fact that there is no oversight or tracking of the trend.

In November the AJC first contacted the Georgia Attorney General’s office, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, and the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) for data on juvenile lifers to understand where the state stood in adhering to the Supreme Court’s rulings.

Both the AG’s office and the state parole board said they did not have any data tracking juvenile lifers. GDC provided data, but it was filled with errors that made it almost useless. The department’s Assistant General Counsel Tim Duff ended up waiving AJC’s Open Records Request fees since the given spreadsheets were erroneous and the department was unable to provide the requested data.

“It’s incredibly frustrating,” said Loudon-Brown, who mainly specializes in death penalty cases but began tracking juvenile lifers in his spare time, keeping a Microsoft Word document with all the juvenile lifers he’s aware of.

“If you never really know if you have the entire sample of children who are serving life without parole it makes it incredibly difficult to stay on top of the issue and to make sure their rights are protected,” said Loudon-Brown, who maintains his list via sporadic record requests to GDC, emails from a network of defense attorneys across the state, and news articles.

“The way I often double-check is I just Google it,” he said, a method he admits is susceptible to error and oversights.

To create its database, the AJC collated GDC’s spotty data with Loudon-Brown’s and then cross-checked it with data compiled by the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. The AJC then contacted district attorneys in the state’s judicial circuits to fact-check and confirm cases their offices had prosecuted.

The process highlighted numerous gaps, including two sentences of life with the possibility of parole that should not have been included and six cases that had not been in Loudon-Brown’s tally.

The AJC’s attempt to confirm the data was often the first time many state and local leaders were made aware of the trends.

“The numbers surprise me. I would not have thought there were that many,” said Skandalakis after AJC shared its data with him.

While Skandalakis said he couldn’t weigh in as to whether any of the sentences were incongruous with the high court’s intentions, he was vocal about the state’s data gap, which he said limits the legislature’s ability to make good policy.

“We need to be better at it,” he said. “All of us, not only the Georgia Department of Corrections but prosecutors, the courts, everybody needs to be better at it.”

Loudon-Brown believes one solution would be a requirement that prosecutors must give formal notice to the state if they want to use the punishment, much like they are required to do with the death penalty.

“You have to have some sort of database, statewide monitoring procedure to make sure a kid doesn’t get lost,” he said, stressing that figuring out who is a juvenile lifer shouldn’t be more difficult than tracking who is on death row.

In his mind, it’s the equivalent of a death penalty sentence. “It’s death in prison,” he said.

Marking life’s milestones, dreaming of release

Battle struggled when he first went to prison. In 2016, he got in trouble and was charged with gang activity, possession of a weapon (a sharp metal object), and aggravated assault at Fulton County Jail while awaiting a court appearance. He was two years into his forever sentence.

Credit: Contributed

He was learning to survive in a chaotic and violent environment.

Macon State Prison, which he has called home for nearly a decade, is one of the state’s most dangerous correctional facilities. In 2020, six inmates were slain in just six months.

Battle was also still young. He was still in the eye of the storm and stress that Hall wrote about so many decades prior.

And just as Hall predicted, he has also since mellowed out.

“He has grown up since he’s been incarcerated. He became a man that I couldn’t help him become,” Reese said dabbing her eyes as she spoke.

Nearly 30 years old, Battle is today described by family and friends as level-headed and calm; an independent thinker.

“When he first went in, he was wilding because of the group -- the group of people he was hanging around. Now when you see Marcus he’s so mature,” said Reese, explaining that it is Battle — the former dropout — who is encouraging his younger siblings to stay in school and graduate. “I never thought he’ll be the one telling everyone to be strong. And in spite of him being locked up, he keeps his head up and he keeps pushing.”

The past few years Battle hit some important milestones: He enrolled in a GED program this spring and proposed to his fiancee, Shontelle Clark, in 2020. The two, who met via a mutual friend, started with letter writing five years ago before she eventually made his call list. She now makes bimonthly trips to visit her “man,” as she calls Battle.

The situation, Clark acknowledges, may seem unconventional to some. But you also can’t help who you love, said the 35-year-old, explaining that they talk about moving out of state, maybe to Colorado, and having kids one day. In the future that they’ve imagined, Battle is working to help others overcome childhood struggles like the ones he faced.

“His thing is to start a nonprofit organization to just help the youth,” said Clark. “Him growing up with lack of guidance from a male role model, that’s kind of what steered him into, you know, the street life.”

It’s this vision that keeps Battle, and his close ones, going each day.

But it’s also one that comes with very clear obstacles: Battle is still sentenced to die in prison. And even if he was — despite Fulton County’s recommendation — able to get a life-with-parole sentence, he’d still have to wait another two decades to hit Georgia’s requirement of serving 30 years before being eligible to go in front of the parole board.

And that is not a guarantee that he will ever go home, as evidenced by the state’s pre-Miller lifers.

“By sentencing someone to life without parole at age 17, that means they could live to 80 years old and never be heard from again,” said Loudon-Brown, acknowledging that a parole-eligible sentence by no means assures release. It simply guarantees that a kid is not forgotten, that they get the opportunity to grow and change and have a chance at rehabilitation.

“We will know for sure that this 17-year-old, when he’s 47, is seen still and is on somebody’s radar,” said Loudon-Brown.

Reese, who has been sober for over 20 years, is more inwardly reflective when discussing her son’s case, thinking of her own opportunities at redemption; the fact that society didn’t cast her away or judge her based on her lowest moments and worst choices.

“I had to get my life together for my children. I did it only because they gave me a second chance,” she said, speaking of her time in court-mandated rehab.

“They never gave my boy a second chance.”