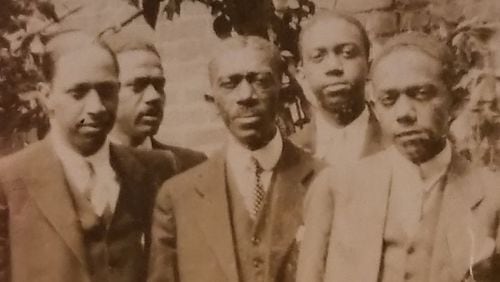

Growing up, David Getachew-Smith heard stories about a distant relative who served in a prominent position in the Hogansville post office.

It didn’t mean much to him at the time, but years later, he would discover that the man, Isaiah H. Lofton, was part of Georgia’s troubled racial past.

In 1897, President William McKinley appointed Lofton as postmaster of Hogansville, a small town located roughly an hour southwest of Atlanta.

The appointment of Lofton, a Republican Party organizer and schoolteacher, riled many whites in the community, resulting in a boycott of the post office and a failed attempt to kill him by unknown gunmen, according to the Georgia Historical Society.

His story “is important in that it reminds us that racial progress in Georgia was difficult and that there were forces along the way that were determined to keep African Americans, regardless of qualifications, in a position of servitude,” said Getachew-Smith, Lofton’s great-great-grandnephew and a chief senior assistant district attorney for Fulton County.

RELATED: Stories from the Soil: Remember the victims of racial lynchings

Lofton, however, is finally getting recognition.

On Saturday, the Georgia Historical Society, in conjunction with the city of Hogansville, will dedicate a new Georgia Civil Rights Trail historical marker at West Main and Boozer streets, recognizing the attempted assassination of Lofton.

It is part of the Civil Rights Trail initiative that tells the story of the state’s involvement in the freedom movement. So far, about 40 markers have been erected, with more to come.

RELATED: White mobs reduced black community to rubble

MORE: Family reveals 76-year-old secret in Georgia lynching

Several of the markers are located on or near sites of racial violence, including Moore's Ford, where a Walton County mob lynched four black citizens.

Lofton was appointed during a turbulent time in the American South.

Reconstruction had ended and racial tensions and violence were on the rise.

From 1882 to 1968, there were more than 4,700 lynchings in the United States, according to the NAACP. Most of the victims of racial violence were African Americans, and dozens occurred in Georgia.

Lofton was among dozens of African Americans who were appointed by McKinley to postal jobs, including postmaster.

MORE: Marker provides context to Confederate monument

Many received a cold — if not dangerous — welcome. They faced intimidation, boycotts and death. In 1898, Lake City, South Carolina’s first black postmaster, Frazier B. Baker, and his young daughter were murdered by a mob after he refused to resign.

Lofton survived and later fled up North. His shooting, though, was referenced in books and several newspaper articles.

Getachew-Smith, an amateur genealogist and former Fulton County Juvenile Court judge, said his family never talked much about Lofton. Experts say that’s not uncommon among the families of victims of racial lynchings and violence.

Perhaps older members of his family feared retribution or felt shame that Lofton was forced to leave. Perhaps Lofton himself wanted to leave the past in the past.

Getachew-Smith isn’t sure.

He does know Lofton and his family made a new life in Washington, D.C.

University of Georgia Associate Professor and author Tony B. Lowe has done extensive research on Lofton. A native of Hogansville, Lowe said on trips home he spent time with some of the town’s old-timers, fueling his passion for history. During several of those conversations, they mentioned Lofton.

When some of the community’s older residents died, Lowe decided, “I couldn’t just sit on this story. I felt a kind of urgency and responsibility.”

He began researching the incident. “What they told me was just the tip of the iceberg. He received threats from the (Ku Klux) Klan. They wanted to run him out of town and he refused to go. He said I have every right to the job and refused to back away from it. Even after the shooting, he refused to go.”

Lowe said that incident and the one in South Carolina helped propel efforts to establish a national civil rights protection organization.

“Hogansville was on the civil rights fault line,” he said. “We played our part in the national civil rights story.”

Hogansville Mayor Bill Stankiewicz said it’s important to recognize such sacrifices.

“As uncomfortable and as troubling as some of the occurrences were, we can’t ever forget that they happened.”

About the Author