The 2018 election season has finally ended. It's over. Finis.

Which means that the time is now ripe to take a cold-eyed, dispassionate and non-partisan look at the Mystery of the Missing 100,000 Votes.

This is not about Georgia's race for governor, but about the lieutenant governor's contest. And the puzzle isn't hidden, but sits on the secretary of state's public website, staring at us like one of Edgar Allan Poe's purloined letters.

Let us begin the hunt by saying that Sarah Riggs Amico, the Democrat who lost to Republican Geoff Duncan by 123,172 votes on Nov. 6, is not asking for a do-over. Yes, a lawsuit has been filed challenging the results, but she is not a party to it.

Amico is more interested in finding an explanation. “I don’t think this needs to be looked at as a question of outcome. It needs to be looked at as a question of election integrity,” the former candidate said Monday at the Cobb County headquarters of her family’s trucking firm.

Given that the state Legislature is about to embark on a fierce and expensive debate over the replacement of thousands of voting machines in all 159 counties, her search could be an important one.

Every other November, in general elections, Georgia voters are asked to plow through a long ballot. Usually, though not always, a race for governor or the U.S. Senate tops a long list, followed by contests for lieutenant governor, secretary of state, attorney general, and so on.

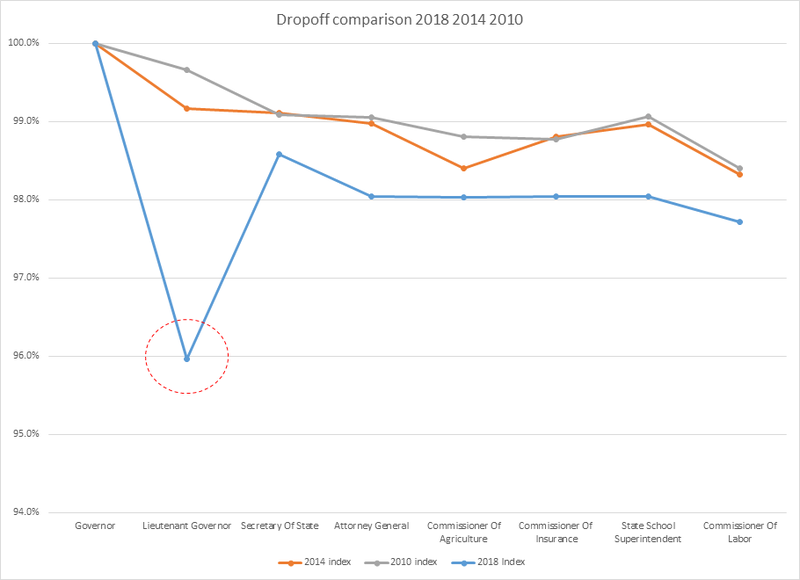

With each down-ballot contest, more voters bleed away. In election after election, graphs of the phenomenon resemble a gentle, downward slope.

That’s not what happened on Nov. 6. The pattern changed rather suspiciously.

In the race for governor, 3,939,328 voters cast a ballot. But in the No. 2 race for lieutenant governor, 159,024 of those voters – about 4 percent — dropped away.

Then, in the next race down, 103,290 of those supposedly lost voters suddenly regained their interest and voted in the secretary of state contest. From there, the traditional downward slope of disappearing voters resumes.

Those numbers argue that Georgia’s race for lieutenant governor became a canyon of lost votes. Here’s how it looks:

This was Amico’s first bid for public office. “You try to keep a level, analytical head, and you also try to keep a good amount of humility. And in the beginning, my first thought was I may have just been a weaker candidate in some fashion that didn’t know,” Amico said. “Or maybe there was some really effective effort to sully my campaign that I wasn’t aware of.”

In times of crisis, candidates often fall back on their professional backgrounds. In her unsuccessful struggle to pull Republican Brian Kemp into a runoff for governor, Democrat Stacey Abrams, a lawyer, went to court.

Amico has a master’s degree from Harvard Business School. She and her husband Andrea revel in statistics. They called the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Election Data and Science Laboratory. They brought in Michael Herron, a Dartmouth College professor specializing in ballot irregularities.

Amico and her husband have generated reams of statistics, and are in search of more.

The first and perhaps most important thing that Amico learned was that the canyon of lost votes probably wasn’t about her. Not personally. Among absentee ballots cast, there is no violent drop-off in the race for lieutenant governor. The gentle downward slope rules. The canyon appears only among early votes or Election Day votes, all cast via touch-screen voting machines.

Paper absentee ballots and early, machine-generated votes were flowing in at the same time. “If there were a point in time at which my fortunes politically changed, the curves would decline together. But what you see is that the differential is completely driven by mode,” Amico said.

In this case, “mode” is statistic-speak for “machine.”

Several possible factors, jointly or singly, could have caused this cratering of votes. Ballot design is one. Being left off the ballot on some machines is another. Then there’s the uploading of the results, and the actual tabulation – both human and thus fallible activities.

Oh, and a couple more bits of evidence: The voting anomalies appear to have happened within the most Democratic of Georgia’s counties, including DeKalb, Fulton and Clayton. Statewide, Amico appears to have been affected more than Duncan. She ran 95,119 votes behind Abrams, a 5 percent drop-off. Duncan ran 26,670 votes behind Kemp, a 1.3 percent decrease.

I asked Amico whether competency among local election officials might be an issue. “I don’t think so,” she answered. “This is where it’s tricky. I don’t want to make assumptions, because I think this issue is so important, I think it really deserves a fact-based investigation. I have hypotheses of what happened. I don’t know if it’s productive to share them in the absence of the facts.”

To that end, six days after her defeat, Amico asked Acting Secretary of State Robyn Crittenden to take a look at the statistical anomalies we’ve mentioned above. If these were lab results rather than election results, any doctor would be on the phone with the patient in a heartbeat, Amico argued.

Again, the former candidate wasn’t contesting the results of the contest. “While the number of residual votes in the lieutenant governor’s race is unlikely to affect the outcome of my race, more needs to be understood about the functioning of the…machines used on Election Day in 2018,” Amico told Crittenden.

The acting secretary of state has thus far declined to be drawn into any inquiry. “Voters are not obligated to cast a vote in each contest appearing on their ballots. You also readily acknowledge that the rate of residual votes in your race is unlikely to affect the ultimate outcome,” Crittenden replied.

But if losers can raise questions only if they can already prove they’re winners, we have a flaw in the way things ought to work.

“The system is designed to almost ensure candidates will never get an answer to what made that happen. We know this only happens on machines,” Amico said. “The only way to know what drove this on the machines is to look at the source code. And the only way to do that is to contest your election. But the only way to get a contested election is to show the proof.”

Crittenden didn’t close the door entirely. She indicated a willingness to sit down with Amico and her statistics. And now that the runoffs are over, Amico said she’ll take Crittenden up on the offer.

In the meantime, Amico is pursuing that source data from several counties through the state’s open records law, though it might be January before she has enough to say for sure what happened on Nov. 6.

Getting an answer before Georgia purchases a new-generation voting system would seem to be important. You’re probably familiar with that phrase coined by Bert Lance, the old Jimmy Carter hand: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

There's an unspoken corollary to that old saw: If you don't know what's broke, or don't want to know, you can't fix it.

About the Author

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/P7DYBH6TO7FEKG4SUXQQKADRXE.jpg)