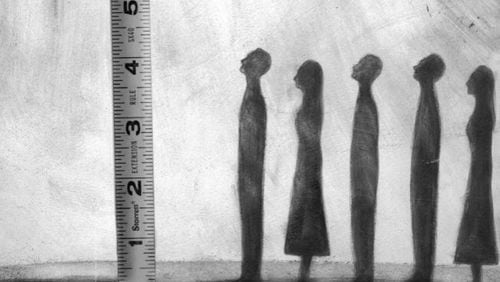

If standardization is not good for students, is it any better for teachers?

Eric Wearne takes that up today in a guest column where he urges an end to a mandated performance assessment for teacher candidates that he deems ineffective and without any evidentiary justification.

Wearne is an associate professor with the Education Economics Center at Kennesaw State University. He spent seven years as an assistant and associate professor of education in the teacher preparation program at Georgia Gwinnett College, as well as several years as a state-level official at the Governor's Office of Student Achievement.

By Eric Wearne

We often hear about looming teacher shortages. Putting unnecessary hurdles in front of prospective teachers clearly does not help this issue. One major hurdle in Georgia which prospective teachers face is the Georgia Professional Standards Commission's requirement that all teacher candidates complete the edTPA, or Educators' Teacher Performance Assessment, for full certification into teaching.

The edTPA was developed at Stanford University, and self-describes this way: "edTPA is a performance-based, subject-specific assessment and support system used by teacher preparation programs throughout the United States to emphasize, measure and support the skills and knowledge that all teachers need from Day 1 in the classroom."

Since 2015, anyone who applied for initial teacher certification in Georgia has been required to earn an acceptable score on the edTPA. To be fully certified, new teachers coming from Georgia’s colleges of education must complete three or four edTPA tasks (depending on their area), and submit them to Pearson Education for scoring. The tasks consist of portfolios of lesson planning, of videos of teaching combined with reflections, and of assessment strategies.

The edTPA tasks themselves aren't necessarily terrible; in fact, in many ways they can be useful for prospective teachers to complete. The real problem is that the state created a one-size-fits-all structure, jumped in with both feet at once, and mandated its use for all new Georgia teachers. Now the coronavirus has prompted the PSC to consider removing the edTPA as a program completion and certification requirement effective July 1, 2020.

They absolutely should do so.

This edTPA policy has caused colleges of education all over the state to alter their curricula, and not necessarily in good ways. Teacher prep programs had to build program machinery and class requirements simply for assessment compliance. The edTPA has brought colleges of education increased costs, state mandates to “ensure quality” (with no proof that succeeding on the edTPA would make teachers better), and forced standardization.

Educators and parents routinely decry standardization in many facets of K12 education today, so why did we mandate even more standardization in teacher preparation? Why would we think obtaining a more expensive, more standardized, more test-heavy degree will do anything but harm the teacher talent pipeline in Georgia?

Here are three other reasons why the edTPA program has been problematic and may contribute to Georgia’s difficulty in attracting teachers over the long-term:

It increases costs to students and taxpayers:

Students must pay, directly or indirectly, the $300 cost for having their assessments scored by Pearson. If teacher candidates do not pass, they must pay again to have their new submission scored.Further, due to the edTPA requirement, schools of education in Georgia have had to hire additional staff to keep up with data compliance, and some have developed remedial courses for students who fail the assessment.

The edTPA doesn't appear to improve teaching:

Research suggests that students don't actually improve their practice because of edTPA – they just work more on test prep strategies for it. Stanford University and test-prep companies have every right to develop products and to sell them. And, colleges of education should be free to purchase their products—or not. If we are going to force a one-size-fits-all edTPA mandate on colleges of education and teacher prep candidates, the burden of proof is on edTPA to show that its program makes teachers better.

Five years after Georgia implemented this mandate, the evidence still is not there. In some ways, this is the same problem Common Core faced. Imagine if Common Core had started as a small group of districts or states voluntarily joining together. If those states' students then showed significant achievement gains, other states would have followed their lead, learned from their mistakes, and the whole process would have been more transparent and less acrimonious. Instead, Common Core, like edTPA, forced standardization upon everyone at once, with no track record of success.

The edTPA ended creativity among ed schools:

Schools of education are very similar to one another across the country, as they must follow similar accreditation rules. The edTPA forces ed schools to prepare students to complete the exact same assignments. This is not at all what most teachers want for their students, but for some reason we are proving very accepting of it in higher education. Education faculty—like faculty in other disciplines—should have more room for creativity.

The PSC absolutely should repeal the edTPA requirement when they meet in June. There are many reasons for teacher shortages: retirements, other options for graduates, especially those in math and science fields, etc. Demographics are hard to predict, and the market is impossible to predict. But one thing we can control are the policies that go into training new teachers.

In this era of the coronavirus, we need to make sure our public school system is as flexible as possible in order to meet the significant challenges facing students and their families—and that includes repealing one-size-fits-all mandates that have no evidentiary basis.